The Great Wireless Hack of 1903

Guglielmo Marconi is considered the father of modern radio, but his initial conception of the wireless broadcasting technology was as a point-to-point system like the telegraph. This, understandably, made wired telegraph operators nervous that their businesses were about to be disrupted by the Italian. One, the Eastern Telegraph Company, enlisted the services of a frustrated wireless pioneer, Nevil Maskelyne," who New Scientist related this week, was "a mustachioed 39-year-old British music hall magician" who played a nasty trick on Marconi and physicist John Ambrose Fleming.

The occasion was a big demo at the Royal Academy of Sciences. Marconi was stationed on a cliff in Poldhu, Cornwall and ready to transmit a message the 300 miles to Fleming's receiver in London. But just as the demonstration was about to begin, the receiving apparatus began to tap out a message in Morse code.

Someone... was beaming powerful wireless pulses into the theatre and they were strong enough to interfere with the projector's electric arc discharge lamp. Mentally decoding the missive, [Fleming's assistant Arthur] Blok realised it was spelling one facetious word, over and over: "Rats". A glance at the output of the nearby Morse printer confirmed this. The incoming Morse then got more personal, mocking Marconi: "There was a young fellow of Italy, who diddled the public quite prettily," it trilled. Further rude epithets - apposite lines from Shakespeare - followed.

That someone, as he soon happily announced, was Maskelyne. And his trick had a point: radio was not as private a channel as Marconi had made it out to be. Wireless messages could both be intercepted and interfered with. Like many good hacks, the mayhem had meaning.

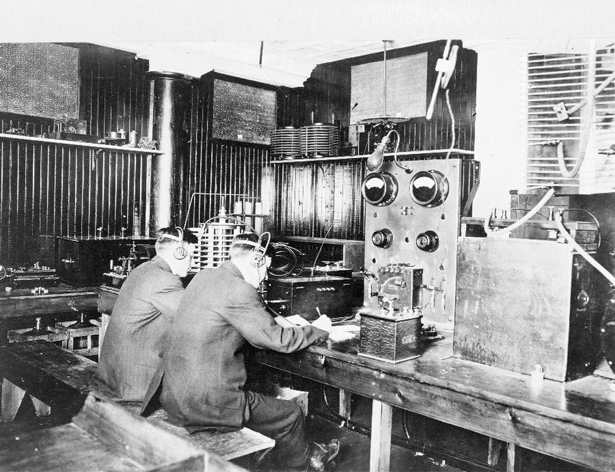

Image: A Marconi radio school. The students are taking messages from ships at sea. Library of Congress.