Moondoggle: The Forgotten Opposition to the Apollo Program

For most of our lunar adventure, a majority of Americans did not support going to the moon. On the 50th anniversary of JFK’s “We choose to go the moon” speech, we excavate this forgotten opposition.

Today, we recall the speech John F. Kennedy made 50 years ago as the beginning of a glorious and inexorable process in which the nation united behind the goal of a manned lunar landing even as the presidency swapped between parties. Time has tidied things up.

Polls both by USA Today and Gallup have shown support for the moon landing has increased the farther we've gotten away from it. 77 percent of people in 1989 thought the moon landing was worth it; only 47 percent felt that way in 1979.

When Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed on the moon, a process began that has all but eradicated any reference to the substantial opposition by scientists, scholars, and regular old people to spending money on sending humans to the moon. Part jobs program, part science cash cow, the American space program in the 1960s placed the funding halo of military action on the heads of civilians. It bent the whole research apparatus of the United States to a symbolic goal in the Cold War.

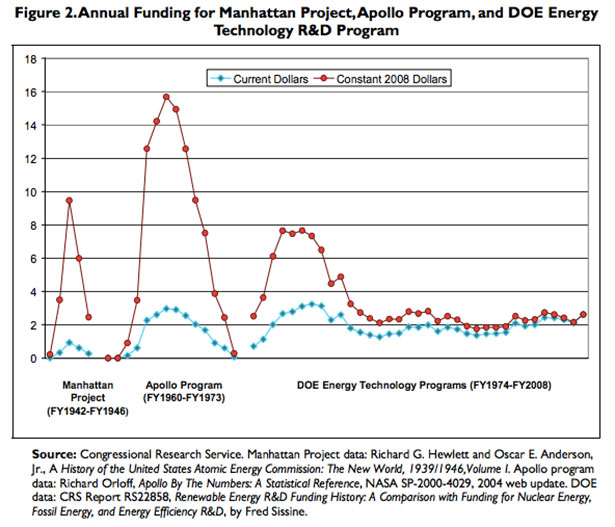

This chart from the Congressional Research Service shows just how extreme the Space Race's funding levels were, even in comparison to the Manhattan Project or the brief fluorescence of energy R&D after the OPEC oil embargo of 1973.

Given this outlay during the 1960s, a time of great social unrest, you can bet people protested spending this much money on a moon landing. Many more quietly opposed the missions. Space historian Roger Launius of the National Air and Space Museum has called attention to public-opinion polls conducted during the Apollo missions. Here is his conclusion:

For example, many people believe that Project Apollo was popular, probably because it garnered significant media attention, but the polls do not support a contention that Americans embraced the lunar landing mission. Consistently throughout the 1960s a majority of Americans did not believe Apollo was worth the cost, with the one exception to this a poll taken at the time of the Apollo 11 lunar landing in July 1969. And consistently throughout the decade 45-60 percent of Americans believed that the government was spending too much onspace, indicative of a lack of commitment to the spaceflight agenda. These data do not support a contention that most people approved of Apollo and thought it important to explore space.

We've told ourselves a convenient story about the moon landing and national unity, but there's almost no evidence that our astronauts united even America, let alone the world. Yes, there was a brief, shining moment right around the moon landing when everyone applauded, but four years later, the Apollo program was cut short and humans have never seriously attempted to get back to the moon ever again.

I can't pretend to trace the exact process by which the powerful images of men on the moon combined with a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era of heroes combined to create the notion that the Apollo missions were overwhelmingly popular. That'd be a book. But what I can do is tell you about two individuals who, in their own ways, opposed the government and tried to direct funds to more earthly pursuits: poet and musician Gil Scott-Heron and the sociologist Amitai Etzioni, then at Columbia University.

Heron performed a song called, "Whitey on the Moon" that mocked "our" achievements in space.

The song had a very powerful effect on my historical imagination and led to me seeking out much of the other evidence in this post. The opening line creates a dyad that's hard to forget: "A rat done bit my sister Nell / With Whitey on the moon." I wrote about this song last year when Scott-Heron died, reflecting on what it meant for "our" achievements in space.

Though I still think the hunger for the technological sublime crosses racial boundaries, [the song] destabilized the ease with which people could use "our" in that kind of sentence. To which America went the glory of the moon landing? And what did it cost our nation to put whitey on the moon?

Many black papers questioned the use of American funds for space research at a time when many African Americans were struggling at the margins of the working class. An editorial in the Los Angeles Sentinel, for example, argued against Apollo in no uncertain terms, saying, "It would appear that the fathers of our nation would allow a few thousand hungry people to die for the lack of a few thousand dollars while they would contaminate the moon and its sterility for the sake of 'progress' and spend billions of dollars in the process, while people are hungry, ill-clothed, poorly educated (if at all)."

This is, of course, a complicated story. When 200 black protesters marched on Cape Canaveral to protest the launch of Apollo 14, one Southern Christian Leadership Conference leader claimed, "America is sending lazy white boys to the moon because all they're doing is looking for moon rocks. If there was work to be done, they'd send a nigger."

But another SCLC leader, Hosea Williams, made a softer claim, saying simply they were "protesting our nation's inability to choose humane priorities." And Williams admitted to the AP reporter, "I thought the launch was beautiful. The most magnificent thing I've seen in my whole life."

Perhaps the most comprehensive attempt to lay out the case against the space program came from the sociologist Etzioni, in his now nearly impossible to find 1964 book, The Moon-Doggle: Domestic and International Implications of the Space Race. Luckily for you, I happen to have a copy sitting right here.

Etzioni attacked the manned space program by pointing out that many scientists opposed both the mission and the "cash-and-crash approach to science" it represented. He cites a 1958 report to the President from his Science Advisory Committee in which "some of the most eminent scientists in this country" bagged on our space ambitions. "Research in outer space affords new opportunities in science but does not diminish the importance of science on earth," he quotes the report. It concludes, "It would not be in the national interest to exploit space science at the cost of weakening our efforts in other scientific endeavors. This need not happen if we plan our national program for space science and technology as part of a balanced effort in all science and technology."

Etzioni goes on to note, and the chart above attests, that this "balanced effort" never materialized.

The space budget was increased in the five years that followed by more than tenfold while the total American expenditure on research and development did not eve ndouble. Of every three dollars spent on research and development in the United States in 1963, one went for defense, one for space, and the remaining one for all other research purposes, including private industry and medical research.

He keeps piling up the evidence that scientists opposed or at best, tepidly supported, the space program. A Science poll of 113 scientists not associated with NASA found that all but 3 of them "believed that the present lunar program is rushing the manned stage. Etzioni's final assessment—"most scientists agree that from the viewpoint of science there is no reason to rush a man to the moon"—seems accurate.

But that's just the beginning of the book. He has many other arguments against the Apollo program: It sucked up not just available dollars, but our best and brightest. Robots could do our exploration better than humans, anyway. We would fall behind in other sciences because of our dedication to putting men on the moon. There were special problems with fighting the Cold War into space. And even as a status symbol, the moon was pretty lousy.

But the space program was great in one way: politically. He notes that President Kennedy sought to help the poor and underprivileged but Congress blocked him. So, as Etzioni tells it, you get a massive public works program cleverly disguised as in conservative, flag-waving garb:

Put before Congress a mission involving the nation, not the poor; tie to competing with Russia, not slashing unemployment. Economically the important thing was to spend a few billions—on anything; the effect would be to put the economy into high gear and to provide a higher income for all, including the poor.

But the space program didn't really work out that way. "NASA does make work, but in the wrong sector; it employs highly scarce professional manpower, which will continue to be in high demand and short supply for years to come," he argued.

He laid out an alternative plan with long-term, science-based goals for research funding, a rational peace with the Soviets, and the creation of palatable social programs to develop rural America and help out the poor. But his voice was lost, and in his last few pages, he may have even predicted why.

"In an age that worships technology, when man is lost among the instruments he has created, the space race erects new pyramids of gadgetry; in an age of materialism, it piles on more investments in things when what is needed is investment in people; in an age of extrovert activism, it lends glory to rocket-powered jumps, when critical self-examination and reflection ought to be stressed; in an age of international conflicts, which approach doomsday dimensions, it provides a new focus for emotional divisions among men, when tasks to be shared and to bind them are needed," Etzioni thundered. "Above all, the space race is used as an escape, by focusing on the moon we delay facing ourselves, as Americans and as citizens of the earth."

The race to the moon may not have been wildly popular among scientists, random Americans, or black political activists, but it was hard to deny the power of the imagery returning from space. Our attention kept getting directed to the heavens—and our technology's ability to propel humans there. It was pure there, and sublime, even if our rational selves could see we might be better off spending the money on urban infrastructure or cancer research or vocational training. Americans might not have supported the space program in real life, but they loved the one they saw on TV.