Christopher Hitchens on the Mildly Fascist Founder of the Boy Scouts

In an Atlantic column, the inimitable writer looked back at the 1908 manual that started a worldwide movement.

"Be prepared." That was the advice the Boy Scouts of America gave its regional directors in a 1991 memo called "Atheism, Girls, and Homosexuality." It was a fraught time -- the organization was juggling multiple lawsuits, and local leaders were overwhelmed by the media attention. To help them fend off the press, headquarters sent out a "comprehensive package of information," beginning with a statement on homosexuality:

We believe that homosexual conduct is inconsistent with the requirements in the Scout Oath that a Scout be morally straight and in the Scout Law that a Scout be clean in word and deed, and that homosexuals do not provide a desirable role model for Scouts.

Statements like that didn't do much to stop the controversy -- or the lawsuits. But the Boy Scouts stuck to their position for decades, asserting just last summer that the ban on homosexuality was "absolutely the best policy for the Boy Scouts." That's why this week's news came as such a surprise: The organization is now poised to adopt a new policy that will let each chapter decide whether or not to accept gay members.

Baden-Powell called Mein Kampf "a wonderful book, with good ideas on education, health, propaganda, organisation."

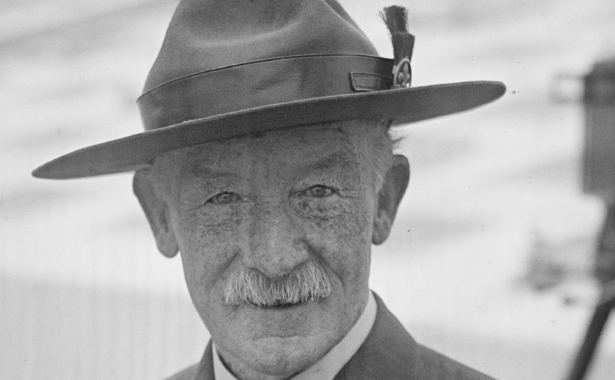

For many current and former scouts, this about-face raises questions about the very character of the Boy Scouts of America, an organization inspired by a British military officer named Robert Baden-Powell. In the June 2004 Atlantic, Christopher Hitchens looked back at Baden-Powell's Scouting for Boys, the 1908 manual that gave rise to an entire culture of "young men in shorts."

As Hitchens writes, Baden-Powell was a peculiar character: "He was a racist and an imperialist and a monarchist, all right, but most of the time to a temperate degree. ... He had charm and courage, and a knack with the young, and he could draw excellent freehand illustrations."

Before founding the scouting movement, Baden-Powell was most famous for writing a book about wild-boar hunting (also known as "pig-sticking"). But his views on outdoor education were closely tied to his concerns about "the moral tone of our race." In Scouting, he stated that "one aim of the Boy Scouts scheme is to revive amongst us, if possible, some of the rules of the knights of old." He praised the Japanese code of Bushido, which taught young men to prize their honor above all else, even if it meant death or suicide.

Baden-Powell was equally enthusiastic about the fascism that began spreading through Europe after World War I. He visited Italy in 1933 and wrote admiringly about the "boy-man" Benito Mussolini who had absorbed his country's Boy Scouts into a thriving new nationalist youth movement. The dictator explained that he'd accomplished this feat "simply by moral force" - an explanation Baden-Powell felt "augers well for the future of Italy."

If Baden-Powell had had his way, the Boy Scouts might have formed close ties with the Hitler Youth. In 1937, he told the Scouts' international commissioner that the Nazis were "most anxious that the Scouts should come into closer touch with the youth movement in Germany." Baden-Powell met with the German ambassador in London and was invited to meet the Führer himself, though the war prevented him from visiting the Third Reich. But he continued to admire Hitler's values, writing in a 1939 diary entry that Mein Kampf was "a wonderful book, with good ideas on education, health, propaganda, organisation etc."

As Hitchens reports, Baden-Powell also seemed to tacitly approve of the Nazi attitude toward homosexuality. When the head of his international bureau told him that a German scout leader had been sent to a concentration camp, Baden-Powell dismissed it by saying the scoutmaster had been taken away for "homosexual tendencies."

By that time, the Boy Scouts of America had developed a strong, independent identity -- the fascist sympathies of an eccentric Englishman had little influence on the way boys camped, hiked, and tied knots across the ocean. But some of Baden-Powell's ideas continued to carry though the movement's DNA -- particularly his emphasis on honor, values, and uniformity. Hitchens quotes a famous metaphor from Baden-Powell's Scouting for Boys that captures some of the issues the Boy Scouts of America are grappling with today:

You should remember that being one fellow among many others, you are like one brick among many others in the wall of a house. If you are discontented with your place or your neighbors or if you are a rotten brick, you are no good to the wall. You are rather a danger. If the bricks get quarrelling among themselves the wall is liable to split and the whole house to fall.

Related stories:

"Boy Scouts Are From Mars, Girl Scouts Are From Venus" by Kate Tuttle

"In Praise of Summer Camp" by Jared Keller

"Eagle Scouts Publicly Reject Gay-Discriminatory Policy" by James Hamblin