The TSA Is in the Business of 'Security Theater,' Not Security

A tell-all from a former Transportation Security Agency worker confirms pretty much every awful thing you've suspected of the ineffective and invasive airport pat downs. That's okay, though: the TSA's main purpose isn't security so much as "Security Theater."

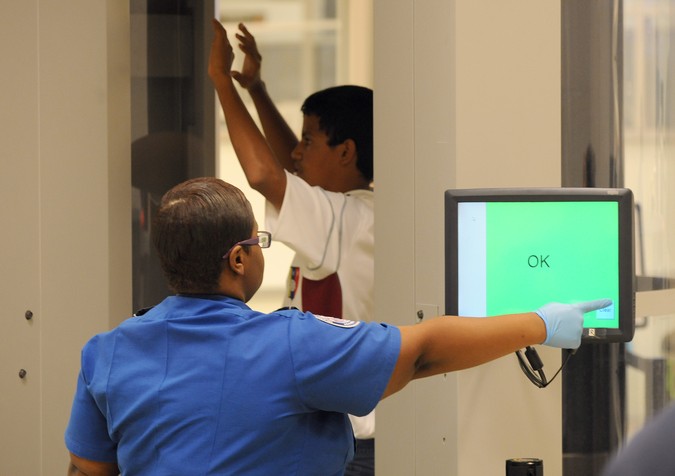

A tell-all in Politico from a former Transportation Security Agency worker confirms pretty much every awful thing you've suspected of those annoying and invasive airport pat downs. But that doesn't mean the TSA is ineffective at its job. That's because the TSA's main purpose isn't security so much as "Security Theater," or the appearance of safety. Let us explain.

Jason Harrington, a former TSA agent, explained in Politico the everyday ridiculousness of the job, a fact that all agents simply accepted as a fact of life. Yes, TSA agents are ogling or making fun of your naked physique in the full-body scans. Yes, they are racially and politically profiling certain people for extra screening ("So it was mostly the Middle Easterners who got the special screening," he writes.) Yes, the body scans are ineffective and can be easily manipulated. (“They’re shit,” a scan instructor said.) So despite being invasive and annoying, the TSA still has some major problems in its security.

But Harrington recognizes the job's clearer purpose — to create the illusion of security. "It was a job that had me patting down the crotches of children, the elderly and even infants as part of the post-9/11 airport security show," he writes. Later, he points to his frustration with "the theatrical quality of nearly all airport security." Essentially, Harrington is referring to "Security Theater," an idea security expert Bruce Schneier explained in detail to CNN in 2009:

Security is both a feeling and a reality. The propensity for security theater comes from the interplay between the public and its leaders.

When people are scared, they need something done that will make them feel safe, even if it doesn't truly make them safer. Politicians naturally want to do something in response to crisis, even if that something doesn't make any sense.

As Schneier later notes, the best terrorist prevention is not to reflexively combat specific bomb plots, but to more invisible tactics like investigations and cultural experts. However, that desire to do something to combat the fear of another attack has simply morphed the TSA into a reflexive body whose rules are consistently a step behind. Terrorists use box cutters ... so no more box cutters or Swiss army knives. A terrorist puts a bomb in his shoe ... so the TSA requires all shoes to go into the X-ray machine. A terrorist puts a bomb in his underwear ... the TSA uses full-body scans. And so on, with liquids and winter jackets and belts and toiletries, all reacting to old methods.

Harrington readily notes that these reactionary policies, as they stand, are ineffective at actually stopping terrorism, as potential attackers can simply change tactics. But this is in many ways an effective way to combat the perception of American insecurity. Terrorism is, by definition, an act that seeks to create fear in its target. By battling those specific fears of shoe and underwear bombs, the TSA can claim some success on the security stage. However, now that Harrington has blown the lid on that theater, don't expect anyone at the TSA to take a bow.

Oh, and in case you were wondering what happens to your confiscated liquids? Well...

One thing I left out of that Politico piece: HELL YES airport employees often drink those bottles of alcohol you surrender at the checkpoint

— Jason E. Harrington (@Jas0nHarringt0n) January 30, 2014