How Americans Got Red Meat Wrong

Early diets in the country weren't as plant-based as you might think.

The idea that red meat is a principal dietary culprit has pervaded our national conversation for decades. We have been led to believe that we’ve strayed from a more perfect, less meat-filled past. Most prominently, when Senator McGovern announced his Senate committee’s report, called Dietary Goals, at a press conference in 1977, he expressed a gloomy outlook about where the American diet was heading.

“Our diets have changed radically within the past 50 years,” he explained, “with great and often harmful effects on our health.” These were the “killer diseases,” said McGovern. The solution, he declared, was for Americans to return to the healthier, plant-based diet they once ate.

The justification for this idea, that our ancestors lived mainly on fruits, vegetables, and grains, comes mainly from the USDA “food disappearance data.” The “disappearance” of food is an approximation of supply; most of it is probably being eaten, but much is wasted, too. Experts therefore acknowledge that the disappearance numbers are merely rough estimates of consumption.

The data from the early 1900s, which is what McGovern and others used, are known to be especially poor. Among other things, these data accounted only for the meat, dairy, and other fresh foods shipped across state lines in those early years, so anything produced and eaten locally, such as meat from a cow or eggs from chickens, would not have been included.

And since farmers made up more than a quarter of all workers during these years, local foods must have amounted to quite a lot. Experts agree that this early availability data are not adequate for serious use, yet they cite the numbers anyway, because no other data are available. And for the years before 1900, there are no “scientific” data at all.

In the absence of scientific data, history can provide a picture of food consumption in the late-18th- to 19th-century in America.

Early Americans settlers were “indifferent” farmers, according to many accounts. They were fairly lazy in their efforts at both animal husbandry and agriculture, with “the grain fields, the meadows, the forests, the cattle, etc, treated with equal carelessness,” as one 18th-century Swedish visitor described—and there was little point in farming since meat was so readily available.

Settlers recorded the extraordinary abundance of wild turkeys, ducks, grouse, pheasant, and more. Migrating flocks of birds would darken the skies for days. The tasty Eskimo curlew was apparently so fat that it would burst upon falling to the earth, covering the ground with a sort of fatty meat paste. (New Englanders called this now-extinct species the “doughbird.”)

In the woods, there were bears (prized for their fat), raccoons, bobolinks, opossums, hares, and virtual thickets of deer—so much that the colonists didn’t even bother hunting elk, moose, or bison, since hauling and conserving so much meat was considered too great an effort. A European traveler describing his visit to a Southern plantation noted that the food included beef, veal, mutton, venison, turkeys, and geese, but he does not mention a single vegetable.

Infants were fed beef even before their teeth had grown in. The English novelist Anthony Trollope reported, during a trip to the United States in 1861, that Americans ate twice as much beef as did Englishmen. Charles Dickens, when he visited, wrote that “no breakfast was breakfast” without a T-bone steak. Apparently, starting a day on puffed wheat and low-fat milk—our “Breakfast of Champions!”—would not have been considered adequate even for a servant.

Indeed, for the first 250 years of American history, even the poor in the United States could afford meat or fish for every meal. The fact that the workers had so much access to meat was precisely why observers regarded the diet of the New World to be superior to that of the Old.

“I hold a family to be in a desperate way when the mother can see the bottom of the pork barrel,” says a frontier housewife in James Fenimore Cooper’s novel The Chainbearer.

In the book Putting Meat on the American Table, researcher Roger Horowitz scours the literature for data on how much meat Americans actually ate. A survey of 8,000 urban Americans in 1909 showed that the poorest among them ate 136 pounds a year, and the wealthiest more than 200 pounds.

A food budget published in the New York Tribune in 1851 allots two pounds of meat per day for a family of five. Even slaves at the turn of the 18th century were allocated an average of 150 pounds of meat a year. As Horowitz concludes, “These sources do give us some confidence in suggesting an average annual consumption of 150–200 pounds of meat per person in the nineteenth century.”

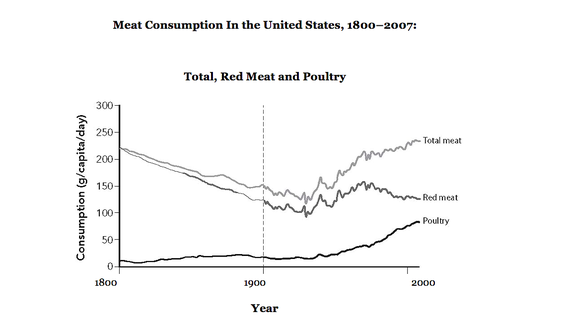

About 175 pounds of meat per person per year—compared to the roughly 100 pounds of meat per year that an average adult American eats today. And of that 100 pounds of meat, about half is poultry—chicken and turkey—whereas until the mid-20th century, chicken was considered a luxury meat, on the menu only for special occasions (chickens were valued mainly for their eggs).

Yet this drop in red meat consumption is the exact opposite of the picture we get from public authorities. A recent USDA report says that our consumption of meat is at a “record high,” and this impression is repeated in the media.

It implies that our health problems are associated with this rise in meat consumption, but these analyses are misleading because they lump together red meat and chicken into one category to show the growth of meat eating overall, when it’s just the chicken consumption that has gone up astronomically since the 1970s. The wider-lens picture is clearly that we eat far less red meat today than did our forefathers.

Meanwhile, also contrary to our common impression, early Americans appeared to eat few vegetables. Leafy greens had short growing seasons and were ultimately considered not worth the effort. And before large supermarket chains started importing kiwis from Australia and avocados from Israel, a regular supply of fruits and vegetables could hardly have been possible in America outside the growing season. Even in the warmer months, fruit and salad were avoided, for fear of cholera. (Only with the Civil War did the canning industry flourish, and then only for a handful of vegetables, the most common of which were sweet corn, tomatoes, and peas.)

So it would be “incorrect to describe Americans as great eaters of either [fruits or vegetables],” wrote the historians Waverly Root and Richard de Rochemont. Although a vegetarian movement did establish itself in the United States by 1870, the general mistrust of these fresh foods, which spoiled so easily and could carry disease, did not dissipate until after World War I, with the advent of the home refrigerator. By these accounts, for the first 250 years of American history, the entire nation would have earned a failing grade according to our modern mainstream nutritional advice.

During all this time, however, heart disease was almost certainly rare. Reliable data from death certificates is not available, but other sources of information make a persuasive case against the widespread appearance of the disease before the early 1920s.

Austin Flint, the most authoritative expert on heart disease in the United States, scoured the country for reports of heart abnormalities in the mid-1800s, yet reported that he had seen very few cases, despite running a busy practice in New York City. Nor did William Osler, one of the founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital, report any cases of heart disease during the 1870s and eighties when working at Montreal General Hospital.

The first clinical description of coronary thrombosis came in 1912, and an authoritative textbook in 1915, Diseases of the Arteries including Angina Pectoris, makes no mention at all of coronary thrombosis. On the eve of World War I, the young Paul Dudley White, who later became President Eisenhower’s doctor, wrote that of his 700 male patients at Massachusetts General Hospital, only four reported chest pain, “even though there were plenty of them over 60 years of age then.”

About one fifth of the U.S. population was over 50 years old in 1900. This number would seem to refute the familiar argument that people formerly didn’t live long enough for heart disease to emerge as an observable problem. Simply put, there were some 10 million Americans of a prime age for having a heart attack at the turn of the 20th century, but heart attacks appeared not to have been a common problem.

Ironically—or perhaps tellingly—the heart disease “epidemic” began after a period of exceptionally reduced meat eating. The publication of The Jungle, Upton Sinclair’s fictionalized exposé of the meatpacking industry, caused meat sales in the United States to fall by half in 1906, and they did not revive for another 20 years.

In other words, meat eating went down just before coronary disease took off. Fat intake did rise during those years, from 1909 to 1961, when heart attacks surged, but this 12 percent increase in fat consumption was not due to a rise in animal fat. It was instead owing to an increase in the supply of vegetable oils, which had recently been invented.

Nevertheless, the idea that Americans once ate little meat and “mostly plants”—espoused by McGovern and a multitude of experts—continues to endure. And Americans have for decades now been instructed to go back to this earlier, “healthier” diet that seems, upon examination, never to have existed.

This post is adapted from Nina Teicholz's The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat, and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet.