The Graffiti That Made Germany Better

Berlin's architecture blends the tragedy of the past with redemption in the present and renewal in the future.

BERLIN—One Thursday in March, Angela Merkel, the chancellor of Germany, strode the light-bathed halls of the Reichstag building in Berlin on her way to its plenary hall, to address Germany’s parliament on Russian aggression in Ukraine. Her pace was purposeful. And yet, even without stopping, she must have glanced, for the umpteenth time, at the hallways’ walls, as almost everyone does when inside this building, the German equivalent of America’s Capitol. That’s because they are not only pockmarked by bullet holes but also covered by Cyrillic graffiti—faded but meticulously preserved.

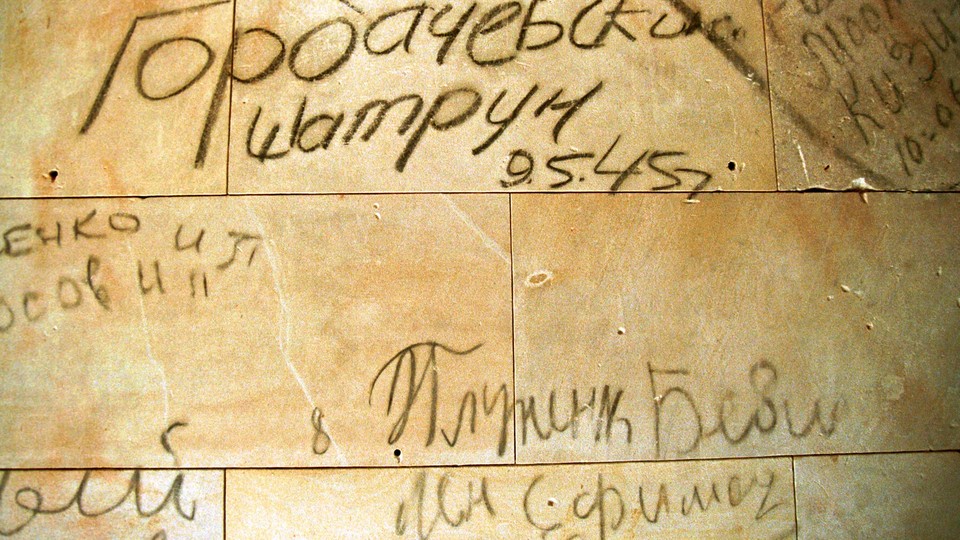

Young Russians scribbled the graffiti after they took the Reichstag on April 30, 1945. The Soviets regarded the building’s capture as symbolic of their overall victory against Nazi Germany because they mistook it for “Hitler’s lair,” as one graffito calls it. (Adolf Hitler, in fact, had never given a speech in this building and committed suicide on the same day in his actual lair, a bunker 10 minutes away on foot, abutting the grounds of today’s Holocaust Memorial.) Some of the Russians wrote on the walls in charred wood that they found lying around. Others wielded red or blue chalk, which they had used during their push into Germany to mark the shifting frontlines on their maps: red for the advancing Red Army, blue for the retreating Germans.

Most simply wrote their names (“Ivanov,” “Pyotr,” “Boris Victorovich Sapunov”) as they would today take selfies. Or they marked the dates and routes of their personal journey (“Moscow-Smolensk-Berlin, May 1945”). “We weren’t proud,” said Sapunov, the first Russian to find his own name again after the graffiti’s restoration in the 1990s. “We were drunk. And we were afraid that we could still be shot right at the end.” Some of his comrades vented different emotions. Their phrases ranged from standard public-toilet fare to the apparently unspeakable (the Germans, often at the suggestion of the Russian embassy, removed some graffiti in the 1990s). Only one vulgarity remains today, barely legible in the building’s southeastern corner: “I fuck Hitler in the arse.”

***

No other capital deals with its past quite as Berlin does. At one extreme are cities like Beijing, where people traversing Tiananmen Square still look up at a huge portrait of Mao Zedong. Such architecture suggests obstinate denial. Jerusalem is at the other extreme. Like Berlin, it arguably has “too much history.” But its past, unlike Berlin’s, is not even really past, with many public spaces still contested by Jews, Muslims, and Christians. It is like Berlin before the Wall fell.

Then there are those countries—including America, Britain, and Russia—whose architecture constructs a fundamentally heroic narrative of their identity. A visitor to Washington will be awed by memorials to its eponymous founding father and to Jefferson and Lincoln, while the surrounding streets teem with victors on horseback. The style evokes the classical splendor of Rome. Sometimes nostalgia peeks through an urban landscape. Central Paris is in effect less a city than a vast museum to France’s former gloire. Other capitals have already passed through nostalgia and preserve the past with an essentially archeological style, as in Rome or Athens.

Berlin also has a few victors on horseback. Most prominently, there is the Alte Fritz (Old Fred, or Frederick the Great, the Prussian king who turned his country into a great power). But these statues are not the city’s architectural leitmotif. By harking back to the distant and mostly positive Prussian enlightenment, they merely frame the defining disasters of Berlin and Germany: world war, holocaust, defeat, division.

Instead, the dominant narrative is tragic, but with redemption in the present. The reunification of the city (and country and continent) in 1990, and the move of the German capital from Bonn to Berlin during the following decade, provided the opportunity and the physical space to express this narrative architecturally. Many public buildings built or rebuilt during this time visually acknowledge the disasters of the past but surround them with the achievements of the present. The combination constitutes an exhortation for the future. The Reichstag is perhaps the best example of how this distinct style came into being.

***

For half a century after 1945, the graffiti on the Reichstag’s walls were forgotten and indeed inadvertently hidden. After the building’s sloppy first restoration in the postwar years, when the Reichstag was in the British-controlled sector of the city, tacky paneling covered the scribbles and bullet holes. But in 1995 the graffiti re-emerged, as the past is wont to do. A British architect, Norman Foster, was rebuilding the Reichstag to house the reunified Germany’s parliament, which was still seated in the modest and sleepy postwar capital of Bonn. Workers pulled the plaster off the walls and at first didn’t realize what they’d found. Once it became clear, the controversy was instantaneous.

What should Germany do with the graffiti? What was the proper role of these, or any, reminders of Germany’s dark past—of its crimes against humanity and subsequent devastation—in the new Germany’s parliament building and capital?

“‘Away with it,’ said some members of parliament. Others said, ‘That too belongs to our history,’” recalled Rita Süssmuth, a doyen of German postwar politics and the president of the parliament at the time. “Some said, ‘No way, we can’t let ourselves be humiliated again. This is over, and it mustn’t become visible again.’ They were more on the right, but all the way through [the political spectrum]. ... But I always said that this makes us stronger, not weaker. It makes humanity stronger.”

And yet even Süssmuth soon realized that keeping all the graffiti was out of the question. She refused to repeat the worst messages to me but said that some spoke of Russian “sabers” stabbing German “sheaths” or “vulvas.” Süssmuth was eight years old when the war ended and remembers its aftermath, including mass rapes by the conquering Russians. “And the victims weren’t just women, as we saw again in the Balkan war,” she explained. “It was women and men, girls and boys.” Her voice, always feeble, became even more halting when I asked her to recall the horrors of both wars again. Atrocities in the former Yugoslavia were occurring as she made her decisions about the graffiti.

I asked Süssmuth whether she ever imagined an elderly German woman who had been raped in 1945 standing before the most explicit graffiti. “Yes, and I couldn’t have answered for that. There are limits, as in cabaret or comedy, the fine line where it tilts,” she told me. Freedom of speech and opinion is sacrosanct, she thinks, as is art in all forms. But you still have to respect what people can bear.

An initial consensus emerged to merely document what the graffiti said, which in many cases was as simple as “we survived,” she recalled. But she advocated going a step further and preserving and even displaying the messages. “Yes, [the Russians] were here, and that was [the Germans’] end, and simultaneously our liberation,” she told me. Gradually, she convinced her skeptics and her view prevailed.

This transformation in German perceptions of their own Stunde Null (zero hour)—from “our end” to “our liberation”—unlocked what has since, intentionally or not, become a distinct theme in Germany’s political discourse and an accompanying aesthetic in its public art and architecture. The past and its scars must never be hidden. They must instead be acknowledged, preserved, and displayed as an implicit reprimand to be moral and responsible in the here and now.

All these “stories of suffering, of the rupture, of the accepting of guilt, this official treatment of guilt is part of German representation,” said Heinz Jirout, an architect and guide in Berlin. “I don’t see that anywhere else.” He certainly does not see it in his own home city, Vienna, which he left more than three decades ago. After World War II, the Austrians rebuilt their capital to regain as much as possible of its old Habsburg splendor. Today, Vienna looks as though nothing much happened there between 1938, when Hitler annexed his native country, and 1945. By contrast, Jirout noted, in the German capital the new aesthetic has subtly become “a basis for a new identity” and “a form of strength.”

All countries, of course, have memorials to their traumatic moments—the Japanese to Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the Americans to Vietnam, and so forth. But these tend to be discrete monuments, standing apart physically and narratively. Even Berlin’s commemorations began in this style. Between 1957 and 1961, officials in West Berlin, then an island behind the Iron Curtain, commissioned the architect Egon Eiermann to rebuild the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtnis-Kirche, usually called the Memorial Church, which had been bombed to rubble in 1943. Eiermann’s plan was to raze it completely and put a modern structure in its place. But after sustained protests, he kept the ruin and surrounded it with a modern tower, church, chapel, and foyer. Yet the old and the new elements are simply standing next to each other, without any interaction. They are not yet integrated into a new narrative. Berliners call the church the “hollow tooth.”

Integrating the old and unbearable with the new and hopeful only became possible after reunification, and perhaps only in Berlin. “When the Wall came down, all the wounds were opened, not only physically but infrastructurally,” recalled David Chipperfield, a London-based architect who rebuilt the famous Neues Museum, best known for its bust of the Egyptian queen Nefertiti, on Berlin’s Museum Island in the Spree River. Sewage systems, railway systems: Everything had been cut asunder and duplicated in East and West.

“From a physical point of view it’s a broken city, so it’s full of gaps,” Chipperfield told me in his Berlin residence, a modern structure of concrete slabs that he built inside a bomb crater in the former East Berlin. “And the gaps are both physical and mental, if you like. If you go to Paris, there are no gaps. In London, there are hardly any gaps.”

One approach to filling these gaps is to build something entirely new. Both in its former West and former East, Berlin has plenty of ultra-modern structures. Chipperfield’s residence is one. The Jewish Museum, built by the Polish-American architect Daniel Libeskind and opened in 2001, is another, with its angular windows and crooked floors signaling a haunted historical backdrop. But for most public buildings in the city center, it seemed more appropriate to integrate the past than to replace it.

In the case of the Neues Museum, which Chipperfield began working on in the 1990s but which only reopened in 2009, he saw a neoclassical temple dating to the mid-19th century in all its war-scarred ruin. The communists had left the building derelict and on the verge of collapse until it was finally reinforced in the 1980s. As usual in Berlin, history presented itself in all its layers: Prussia, then empire, then anarchy, Nazis, war, communism, and finally liberation.

***

This historical layering of mostly painful memories is a characteristic of many public buildings in Berlin. Take the finance ministry, from which Wolfgang Schäuble has lately been directing Germany’s response to the European economic crisis alongside Angela Merkel. Under the Nazis, the building served as the headquarters of the German Luftwaffe (air force) and thus of Hermann Göring, whom Hitler tapped as his successor. A huge swastika once hung in one of the halls in which I now regularly sit for press briefings. After the Nazis’ defeat, the Soviets used the building as their headquarters until 1948. The following year, the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) formally came into being in the building.

In 1965, the building also witnessed one of the most daring escapes in the history of the Berlin Wall. A brave East German, Heinz Holzapfel, had locked himself, his wife, and his son in a bathroom all day. At night, the family snuck up to the roof and Holzapfel threw a hammer attached to a nylon rope over the nearby Wall. His relatives, waiting on the Western side, fastened a steel cable to it, which Holzapfel pulled up to the roof and attached to a flagpole. Using homemade belts, the family slid down the cable as though in gondolas: first the son, then the wife, then Holzapfel. An East German sentry on site missed the entire operation.

The building’s dramatic story does not end there. After reunification, it housed the agency charged with privatizing state-owned East German companies. Many Ossis (former East Germans) still bear a grudge against the agency for, as they view it, selling off the contents of their lives cheaply to greedy Wessis. In 1991, the agency’s boss, Detlev Rohwedder, was murdered in his living room by a terrorist of the far-left Red Army Faction.

What does one do with such a building? One option is to destroy the structure and replace it with something new, Chipperfield told me. Another is to recreate what it looked like before all the bad stuff. And then there are all the options in between. In the case of the finance ministry, the answer was to preserve its outside much as it looked under Göring, but to make the inside bright, modern, and welcoming. Photo exhibits in the lobby and upper rooms document the building’s gruesome past. The past is there, but the story told on the inside overwhelms the one told by the facades.

***

These decisions never come easily. When Chipperfield redesigned the Neues Museum, he decided that as an architect “my responsibility is to the building. As if it was a Greek vase or a Florentine chapel or anything else. I was the guardian of the fabric that history had left.” But for the Berliners who had lived through the city’s traumas, the task was more confusing and painful. “Nobody really likes the evidence of destruction,” Chipperfield told me. When he decided to preserve the bullet holes on the museum’s walls, somebody came up to him and said, “I was here when the Russians came, I don’t want to see bullet holes in the wall. I saw it the first time around.”

Chipperfield understood the sentiment, but he ignored it. Or rather, he overrode it. He kept the bullet holes and other scars of history, but merged them with new structures. Modern columns prop up older and damaged walls, for example. Most visitors find the juxtaposition beautiful.

“I think it helped that I was from the outside,” he now reckons. Chipperfield, like Norman Foster, is British—a fact that has added a sense of resolution and irony to the public debate over Germany’s architecture. “Destroyed by Britons, rebuilt by Britons,” as Jirout, the Austrian-born architect, put it to me.

But timing and location were the crucial factors. Cities in West Germany were rebuilt quickly after the war, often with structures that now look cheap and deface formerly beautiful places such as Stuttgart or Hanover. Many East German cities were rebuilt to fit the ideological aesthetic of communism and look even uglier. And neither West nor East Germany in the postwar years was very interested in integrating the past into its designs. But central Berlin, long rendered untouchable by the Wall’s no-man’s-land, offered gaps, holes, and rubble for new architectural visions at just the right time. The past was neither too distant nor too close. Above all, the past, both Nazi and communist, was by the 1990s overcome, with all of Germany a stable, open, and free democracy.

It is therefore in central Berlin where examples of the integrationist-historical style accumulate. Germany’s foreign ministry, like the finance ministry, has a modern section and a Nazi-era remnant that interact with one another around a courtyard. The Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities is one of several buildings in which modern glass atriums top former courtyards where the walls still bear bullet holes. The train station at Friedrichstrasse nods on one side to the Holocaust, with statues of Jewish children who once boarded the Kindertransporte from there. On the station’s other side stands the Palace of Tears, now a museum but formerly the checkpoint where East Germans bid farewell to their West German visitors before they took the train back to West Berlin.

This new style has had a profound impact on Germans and visitors alike. The work done to the Reichstag during her term as parliamentary president, recalled Süssmuth, “was decided with very small majorities” in the legislative body. But through these long debates “something very democratic came through,” as all the controversy “quieted down” and gave way to a new consensus that this style was appropriate and uplifting.

Today, the Reichstag building is a testament to the transparent practice of democracy. Its cupola is open to visitors, who can walk a spiral path to the top and peer down through glass at the plenary hall below. Parliamentarians, in turn, can look up and see the visitors. The very first time I watched Angela Merkel give an address—it was a hot June evening in 2012, when parliament had to take an historic vote to rescue the euro—I started inside the chamber and then went up to the cupola, before descending again to see her finish the speech.

Do all visitors understand that this new “transparency”—this intimacy between the people and their representatives—is meant to contrast with the mock-democracy of the Weimar Republic that once foundered in the same place? Do they understand that the Russian graffiti in the halls is a subtle warning against nationalism, hubris, and jingoism? “I think it works. But not everything explains itself,” said Jirout. Then again, that is the nature of effective art and architecture: It’s rarely explicit.

“We shape our buildings, and afterwards our buildings shape us,” Winston Churchill once said. Süssmuth, a professor of pedagogy before entering politics, expands this point to education. “I can turn aggressive kids into [good] ones,” she told me. “I don’t even like the word ‘turn’—that is too much, because the kids actually do it themselves, under the influence of art, or music, or…” She paused, visibly moved. Then she circled her finger, as though taking in the surroundings of her office near the Brandenburg Gate, the center of the reunified Berlin.