At the United Nations, Chicago Activists Protest Police Brutality

The activist group We Charge Genocide described alleged human rights violations to the UN's anti-torture watchdog.

This August, police shot and killed a young black man in Ferguson, Missouri. Witnesses say the victim, Michael Brown, had surrendered and had his hands in the air when he was shot. Numerous protests resulted, as the community demanded that the police release the shooting officer's name and the autopsy results.

That description applies to the death of Michael Brown at the hands of the Ferguson police. But it could also refer to the killing of 19-year old Roshad McIntosh in Chicago on August 24. A number of those who saw the shooting say that McIntosh's last words painfully echoed the chants of Ferguson protestors: "Please don’t shoot, please don’t kill me, I don’t have a gun."

McIntosh's shooting is discussed in a report by We Charge Genocide, a Chicago organization that works to highlight the grinding ubiquity of police violence against people of color in the city. McIntosh's death stands out because of its chilling parallels with the shooting of Michael Brown, but the report makes it clear that police brutality in Chicago is not an isolated or unusual occurrence.

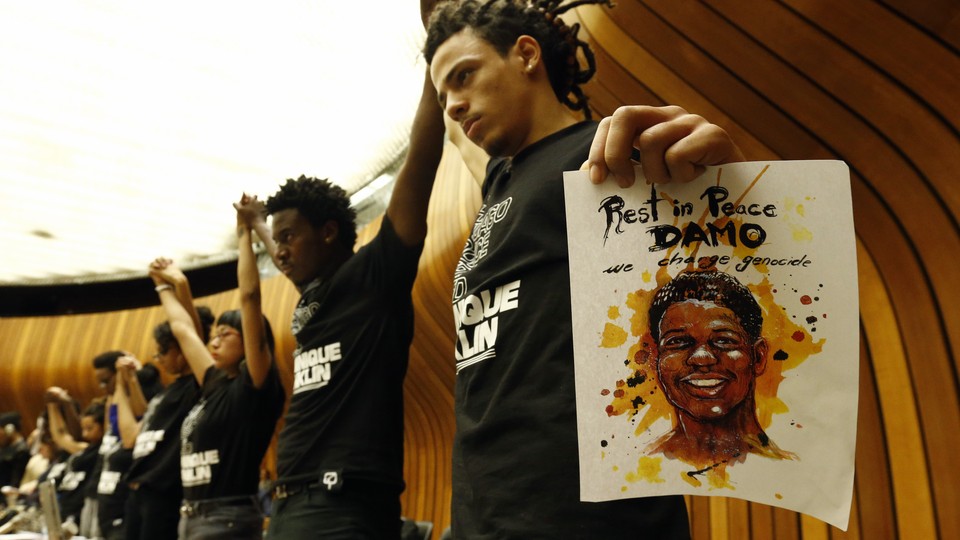

Between 2009 and 2013, more than 75 percent of police shooting victims in Chicago were black, even though African-Americans in Chicago are only about 33 percent of the population. In the first half of 2014, 23 of 27 police shooting victims were black. Taser use is similarly disproportionate: 92 percent of police use of tasers was directed at black or Latino targets. And while tasers are supposed to be a safe form of restraint, they can kill. In May, 23-year-old Dominique "Damo" Franklin was tasered after allegedly stealing a bottle of liquor from a Walgreens. He died in the hospital.

Franklin's death was part of the inspiration for the We Charge Genocide report, according to Mariame Kaba of the Chicago Taskforce on Violence against Girls and Young Women. Franklin had just begun to get involved with activist organizations in Chicago. His death, Kaba said, led to a feeling of "overwhelming despair" and helplessness among many in the community.

In response, Kaba and others in the community turned to history for inspiration. We Charge Genocide was a name first given to a civil rights report by the Civil Rights Congress (CRC), and presented to the United Nations in December 1951. The report detailed lynchings, legal discrimination, and, most relevantly, instances of police brutality. Though largely forgotten in popular memory, the 1951 We Charge Genocide report created a major controversy at the time. The U.S. government accused the CRC of aiding the Soviet Union, and seems to have intercepted copies of the report that had been mailed to UN delegates. U.S. authorities forced CRC secretary William L. Patterson to surrender his passport after he appeared in person at a UN meeting in Paris.

Kaba says that for the new We Charge Genocide organizers, the 1951 precedent was important in that it framed police actions not just as injustice or violence, but as “a deliberate targeting of a group of people for unaccountable violence”—a genocide. Among other abuses, Kaba mentioned the use of torture by police under police Commander Jon Burge between 1972 and 1991, which resulted in false confessions that put innocent men in prison for decades. “The constant surveillance, targeting, [and] torture is as rampant today in this city as it was in 1951,” she added.

The 1951 petition also offered an important plan of action. Last week, eight young activists from Chicago presented their report to the United Nations Committee Against Torture in Geneva, Switzerland. Their report calls on the UN to specifically identify the Chicago Police Department's actions as torture. We Charge Genocide also asked the UN to pressure the CPD to respond with a plan to end its violence against black people in Chicago. Finally, the report asks the UN to recommend a U.S. Department of Justice investigation of the CPD. The Chicago Police Department did not respond to a request for comment.

The UN’s involvement is vital, according to the We Charge Genocide delegation, because local and national authorities have failed over and over again to take action. "The state has proven that it is violent against black people," the We Charge Genocide delegation told me in a group interview, asking to be credited collectively. "We see the system as not just broken, but as fundamentally racist. The problems we see are not things that can be fixed or solved from within that system." A large part of the report, the delegation said, is about the culture of impunity in the CPD, where there seems little institutional will or interest in reducing violence against black people. In one instance, CPD officer Glen Evans was named in 45 excessive force complaints between 1998 and 2008, more than any other CPD officer during that decade. The Independent Police Review Authority recommended his dismissal, but instead he currently serves Commander of District 11 in Chicago.

In the face of what they describe as aggressive indifference by local leaders, the We Charge Genocide delegation said that they were "overwhelmed" at the response of the UN Committee against Torture. The committee, the delegation said, "recognized that black folks and people of color in the United States are victims of endemic and systematic violence at the hands of the police. And that was extremely powerful." They were especially grateful to Essadia Belmir of Morocco, vice-chair of the Committee on Torture, who referred to Dominique Franklin and other victims by name during the hearing.

The international acknowledgement of U.S. violence against its black citizens is important, Kaba explained. "The delegation that's gone is a delegation of young people of color," she told me, “and for them to be able to stand there and recognized, and to speak the name of Damo, and for them to hear the UN use Damo's tasing to ask the U.S. what it's doing…Well, that's amazing."

"Nobody would have known this young's man name,” she added. “They wouldn't have cared. And now maybe something will change around the use of tasers by the CPD. And that matters, if only to the community of the people who cared about him. But maybe it'll matter for other families in the future too."

While the UN may know Damo's name, the rest of Chicago and the U.S. remain largely ignorant of his death. Michael Brown's family also testified last week before the UN Committee against Torture, but most news reports have not mentioned the presence of We Charge Genocide. Even Chicago media has been mostly silent—the Tribune, the Sun-Times, and the Reader do not have a single article on We Charge Genocide between them, as far as I could find.

No doubt all these outlets and more will hurry to cover the Michael Brown grand jury decision, which could come as early as Monday. But that decision, no matter what it is, can only be understood in the context that We Charge Genocide provides. Their report makes clear that Mike's Brown's death wasn't unique. It's part of a routine of violence, only unusual in that the media and the public happened to have noticed. Black youth like Michael Brown, Roshad McIntosh, and Dominique Franklin are dying all the time in America. We Charge Genocide wants the world to know their names.