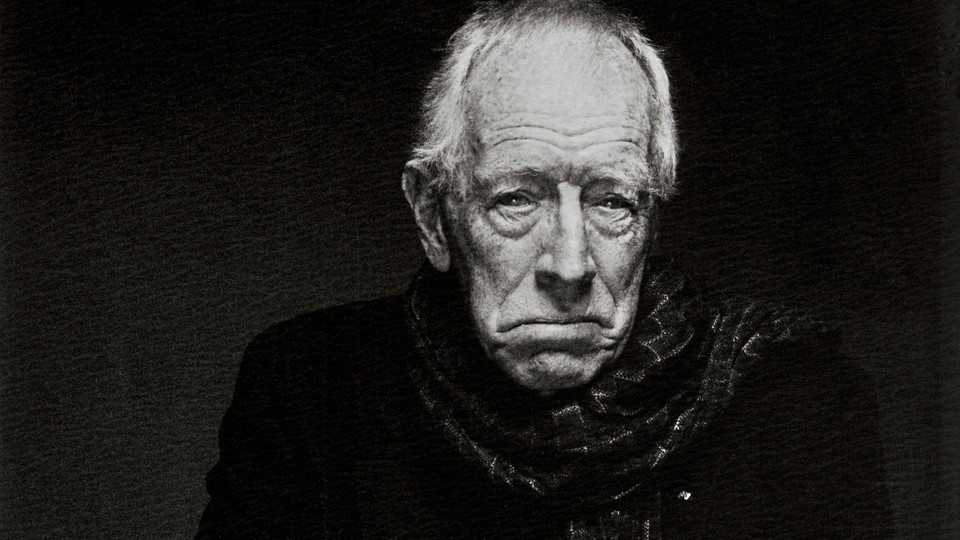

The Greatest Actor Alive

The rich career of the 87-year-old Max von Sydow, whose late-in-life projects include Star Wars and Game of Thrones

The swedish actor Max von Sydow first entered the consciousness of moviegoers as the medieval knight playing chess with Death in Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957). For a significant portion of his six decades onscreen, he has been the greatest actor alive. Now, in his 87th year on Earth, he may be on the verge of becoming a pop-culture icon. In December, he’ll be seen in Star Wars: Episode VII—The Force Awakens, in a role so fogged in mystery that the fan communities have been half-mad with anticipation. (Could he be Kanan Jarrus, the Last Padawan? Sifo-Dyas, maybe? Or—be still, my heart—Boba Fett?) Sometime next spring, he’ll be joining the high-attrition cast of television’s reigning fantasy-adventure franchise, Game of Thrones, whose almost equally febrile fans at least know whom he’ll be playing—a mentor character called the Three-Eyed Raven. In both parts, it’s probably safe to say, his natural authority onscreen will come in handy. His voice is deep, soft, and rich; his body is long and slender; and he wears fantasy-appropriate costumes (flowing robes, hoods, doublet and tights, whatever) as if he were born in them. His presence is commanding, mysterious. If The Seventh Seal were being made today, von Sydow might well be cast as the other guy at the chessboard, the one playing the black pieces. He’d kill.

He is, in short, having the sort of late career that eminent movie actors tend to have, popping up for a scene or two in commercial stuff that needs a touch of gravity, and receiving, as famous old actors do, the honor of “last billing”: after all the lesser players have been listed, a stand-alone credit that reads “And Max von Sydow.” When actors advance in years, you start to get them in bits and pieces—a moment here, a moment there, and then they’re gone. The ones who have the skill, the craftiness, to make an impression quickly are perfectly at home in these limited parts, and that’s the sort of actor von Sydow has been for his entire career. Even in his Bergman days, he wasn’t always the star. (Bergman, like Robert Altman, had a repertory-company approach to casting, and von Sydow played the lead in only six of the 11 features they made together between 1957 and 1971.)

Besides, being an icon isn’t all that tough, compared with real acting. The audience’s memories of past performances do a lot of the work for you. Von Sydow has appeared in well over 100 movies and TV shows, which makes for plenty of memories. Even relatively casual, non-art-house viewers may recall, say, his sodden King Osric in Conan the Barbarian (1982), or the mute, ornery tenant of Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close (2011), or the dapper assassin in the fedora in Three Days of the Condor (1975), or the shifty-eyed bureaucrat of Minority Report (2002). If nothing else, they will surely remember the title character of The Exorcist (1973), in which von Sydow, as a frail, elderly Jesuit, engaged the devil in some pretty fierce soul-to-soul combat.

His role in The Exorcist was in fact the closest he’s come to iconhood before now, and in many ways was a sort of preview of the current “And Max von Sydow” stage of his career. Then in his mid-40s, he aged himself a good 30 years to play the hired-gun demon-fighter Father Merrin; he looks younger than that now. (With his craggy face and receding hairline, and a healthy lack of vanity, von Sydow has never had a problem playing older characters; he seems to relish the challenge.) The role isn’t large—Merrin’s on-screen for only a few minutes at the beginning and then, of course, during the noisy, nausea-inducing exorcism climax—but von Sydow’s quiet power makes the character seem huge, a spiritual force of sufficient size to take on Evil itself. His Merrin combines a gunslinger’s sangfroid and an old man’s terror. During the exorcism, you can feel the effort of will it takes for the old priest to muster his concentration and his strength. What von Sydow brings to The Exorcist is more than the skimpily written part demands, maybe more than it deserves, but this is what he does in even the smallest, poorest roles. Like a novelist, he finds the human details that vivify the character.

Real movie icons don’t bother with that sort of thing. Their familiar personas are all they need. It’s difficult, for example, to imagine Clint Eastwood as Father Merrin, even though in some superficial ways he and von Sydow resemble each other. They are just a year apart in age, are exactly the same height (6 foot 4), have similar lanky builds, and are both unusually striking figures on the screen. (Clint has better hair; Max speaks better English.) Somehow, though, the idea of Eastwood chanting “The power of Christ compels you” in his whispery tough-guy voice seems, not to put too fine a point on it, absurd. When von Sydow recites the line, over and over, it has titanic incantatory power and a very moving undertone of desperation; it sounds like something more complex than God’s version of “Make my day.” Eastwood had to become a director in order to express himself completely. Von Sydow—who directed one lonely picture, Katinka, back in 1988—never needed to. He’s the auteur of any scene he’s in.

Von Sydow has over the years taken on almost every kind of role, in practically every genre. He has played Jesus (in The Greatest Story Ever Told, 1965), the devil (in Needful Things, 1993), and Sigmund Freud (in an episode of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles, 1993). He’s appeared in films by Martin Scorsese (Shutter Island, 2010), Steven Spielberg (Minority Report), David Lynch (Dune, 1984), John Huston (The Kremlin Letter, 1970), Wim Wenders (Until the End of the World, 1991), Ridley Scott (Robin Hood, 2010), Woody Allen (Hannah and Her Sisters, 1986), and Dario Argento (Sleepless, 2001). He has been a voice on The Simpsons. He has played many villains, and more than his share of patriarchs. He’s almost never been cast as a romantic lead, but he’s exceptionally good at husbands.

His roles have come in all shapes and sizes, and in several languages. One of his loveliest late-career performances is in Julian Schnabel’s French-language The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007), in which he plays the 92-year-old father of a stroke victim. In the first of von Sydow’s two scenes, a flashback, he’s being shaved by his son, bickering and bantering—mostly about women—all the while; in just a few minutes of screen time, with lather on his face, he sketches a swift, deft portrait of an old Parisian roué whose powers are fading but whose sense of himself remains miraculously (and very Frenchly) intact. Shave over, he looks in the mirror and says, only half in jest, “God, they don’t make them like me anymore.”

They sure don’t. And as much fun as it is to watch von Sydow transforming a tiny, last-billed part into something unexpectedly resonant, it’s better to see him at full stretch, in chewy, angsty Bergman films like The Virgin Spring (1960) and Shame (1968), for instance, or in Jan Troell’s epic The Emigrants (1971) and The New Land (1972). In those pictures, all in his native Swedish, he exercises his most remarkable gift, for portraying ordinary men in extraordinary circumstances. In The Virgin Spring he’s a medieval landowner, devout and of modest means, to whom something terrible happens: His daughter, on her way to church, is raped and murdered. And he does something terrible in response: With grim determination, he kills her three attackers—one of whom is a young boy—in his own home. For most of the film, von Sydow is steely and righteous, but after he’s taken his revenge, his stern facade begins to crack, his steps become slower, heavier, until at the side of a stream he stops and his erect frame just crumples to the ground, as if it has lost all definition. This is what it looks like when a man’s will, sustained too long, drains suddenly from his soul. Bergman shoots it in a wide shot, from the back; nothing else is required. It’s one of the most beautiful pieces of physical acting you’ll ever see.

In Shame, which is set in the present day, he plays a softer character, a laid-off musician living with his wife (Liv Ullmann, his frequent co-star) on a poor farm on a desolate island. A war breaks out, and the character of the island’s residents is tested; the musician is not among those who pass the test. In this picture, von Sydow’s body language is diffident, indecisive; he shambles around, in pajamas or loose, rumpled clothing, as if he has no idea where he is or what he is meant to be doing. He has a superb comic scene in which, to his wife’s disgust, he utterly fails to shoot a chicken, missing it at point-blank range. (He flaps as uselessly as the bird.) The performance is sometimes painful to watch—this is Bergman, after all—but von Sydow does something very difficult in Shame. He finds poetry in weakness.

The emigrants and The New Land together tell the story of a Swedish farm family that comes to America in the mid-19th century, and because the action of the films covers decades, von Sydow gets to play all the stages of his character’s life, from the early days of his marriage (again to Liv Ullmann) through a trying, work-intensive middle age. Troell’s leisurely style allows for a lot of the quiet, subtle domestic scenes that von Sydow and Ullmann are both particularly good at, and in the course of the movies’ six-and-a-half-hour running time you feel as if there isn’t much you don’t know about these people: how they eat, how they do their chores, how they argue, how they make love, how they trust one another, and, sometimes, how they don’t. The mundane stuff—the moments of strength, the moments of weakness—accumulates, bit by bit, and that approach is, I think, the sort of ground in which an art like von Sydow’s can really flourish. He’s happiest when he can dig deep.

The only Hollywood picture in which he was able to cultivate a character in that way was another 19th-century epic, George Roy Hill’s Hawaii (1966), in which he plays a pious, severe Christian missionary named Abner Hale, who travels from New England to Hawaii and does his damnedest to destroy the islands’ culture. He ages a few decades in this one, too, and although it’s a more conventional movie than The Emigrants and The New Land (and he’s burdened with Julie Andrews as his co-star), von Sydow’s performance is one of his most original, and most memorable. He’s upright and rather forbidding in this, as he was in The Virgin Spring and he would later be in any number of supporting villainous roles, but he isn’t really a villain here. Although the Reverend Hale is wrong about almost everything, his intent isn’t mean-spirited or dishonorable, and as the movie goes along von Sydow manages to instill in the viewer a kind of respect for the character’s stubborn rectitude. He makes us understand, from the inside, a worldview that now seems as strange to most of us as pre-Galilean science.

And 30 years later, in Troell’s Hamsun (1996), he played a man who was even more wrongheaded than Abner Hale and compelled us to understand that man, too. The Norwegian poet and novelist Knut Hamsun was a national institution who in his vain, cranky old age became a vocal supporter of Adolf Hitler—because the Nazis were admirers of his books, and because he believed that the Third Reich would somehow be good for Norway. In the movie, Hamsun is about 20 years older than von Sydow was at the time, and the actor’s portrayal of the character’s irritable, befuddled dignity is improbably, almost inconceivably, moving. Every shaky gesture, every splenetic outburst, every attempt to draw himself up as he once did and assert his flagging pride, tells a story about the discontents of mortality, and you find yourself wondering, How does von Sydow know so much? Did he make a deal with the devil? Or did his opponent in The Seventh Seal whisper in his ear after the game was over? No, it’s just the sort of imagination that some actors, a very few, are blessed with. There’s Laurence Olivier, of course. In the silent era, Lillian Gish. Marlon Brando. And Max von Sydow.