How Many Photographs of You Are Out There In the World?

Now that cameras are ubiquitous, photographs of ordinary people are everywhere, too.

Most of us probably have one weird question that consumes them. No? Okay, well, I do. A lot of places I go, people I don’t know are taking photos. I wind up in some of them, inadvertently. I think about this all the time.

I live in New York City, a place full of people (tourists and non-tourists) taking photos. Every time I bike over the Brooklyn Bridge, as hundreds of tourists take selfies and panoramas, I’m in the background. As people take photos of each other—of Lake Louise, of the White House, of a Bloody Mary at brunch—other people end up in the frame. But how many? How many photographs out there feature you or me in them, in the background, beneath the Eiffel Tower or at the table next to the birthday party? Is it 100? 1,000? 5,000? 10,000? More?

This might seem like a ridiculous question. But theoretically, we’re not far off from a future in which companies using facial-recognition technology could tag you in all those pictures. In fact, Facebook can recognize you in photos even if your face isn’t in them—using what it knows about your body type, your clothes, and your posture.

But right now, actually figuring out how many pictures exist of any one person in the world is probably impossible. Even trying to find someone, anyone, to help me think through this question was a bit like an academic game of hot potato. Every scholar, historian, and academic I contacted referred me to someone else, who then referred me to someone else, who sometimes referred me back to the first person, and so on.

So, it’s tough even to estimate, but bear with me as I try.

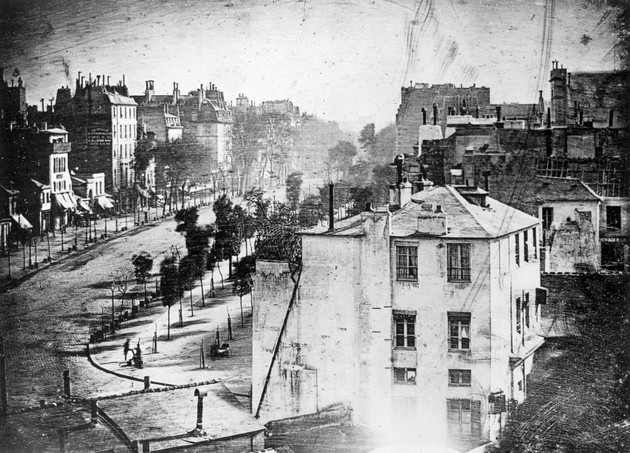

The oldest known photograph with a person in it is the exact kind of photo I’m talking about. The picture was taken in 1838 by Louis Daguerre, and it shows Boulevard du Temple, in Paris.

The street is lined with lamps and trees, and in the middle of the frame is a tiny figure. A man getting his shoe shined, who likely had no idea his image was being captured at all. (In fact, Boulevard du Temple is and was a busy street. When Daguerre took the photo, there were carts and people streaming up and down the street and sidewalks, but only this one man shows up because the photograph had to be taken over the course of 10 minutes. Only the man standing still shows up after such a long exposure.)

A lot has changed since 1838. Cameras have become faster, cheaper, and easier to use. With those changes has come an astronomical increase in the number of photographs taken. According to Photoworld’s estimates, Snapchat users share 8,796 photos every second. In 2012, in a document filed to the SEC, Facebook wrote that “on average more than 250 million photos per day were uploaded to Facebook in the three months [that] ended December 31, 2011.” In 2013, according to Internet.org’s whitepaper, people uploaded 350 million images to Facebook each day.

And those are just numbers from a handful of social-media companies. Weibo, What’sApp, Tumblr, Twitter, Flickr, and Instagram all add to the pile. In 2014, according to Mary Meeker’s annual Internet Trends report, people uploaded an average of 1.8 billion digital images every single day. That’s 657 billion photos per year. Another way to think about it: Every two minutes, humans take more photos than ever existed in total 150 years ago.

Which raises a tricky question about undertaking this calculation in the first place. “Are you talking about any photo that’s ever existed, or photos that exist right now? If you delete the photo does that count? If you have thousands of photos on your hard drive but nobody ever sees, does that count?” asks Sarita Yardi Schoenebeck, the director of the Living Online Lab at the University of Michigan.

After all, that 657 billion number is just photos that were uploaded online, not ones that are stored on someone’s computer. It also doesn’t include security cameras, or closed-circuit systems, or body-worn camera footage, or aerial-drone shots. The United Kingdom has 6 million surveillance cameras in service. According to CrimeFeed.com, the average American is caught on camera 75 time a day. Some of that footage is stored and backed up, while some of it is lost immediately. There’s a channel on my television that broadcasts traffic cameras across the city, including one at Times Square, where there are always people who probably have no idea I’m watching them in my living room. There’s a livestream of Abbey Road. And real-time footage of Piazza di Spagna, one of the famous public squares in Rome.

So trying to figure out what infinitesimal percentage of the 657 billion photos uploaded to social-media sites this year I am in is, perhaps, a ridiculous idea. But that has not stopped me from trying.

First I tried to really narrow the question down as much as possible to this: How many photos that have been uploaded to social-media sites, and still exist on those sites, am I in the background of? This eliminates photos that may have never been uploaded, photos that may not exist online anymore, Snapchats, security cameras, and video footage of tourists who are recording their entire walk through a museum or monument.

The number of photographs you’re in is a direct function of the number of places you’ve been that are highly photographed. “If you go to many places around the world like the Taj Majal, it’s not as though every person in the world is visiting there, it’s some subset of people,” Schoenebeck says. In other words, rich people get to travel more, and are therefore probably in more photos.

To eliminate this variability, I decided to just try to estimate my own photo-footprint. So the first thing I did in my futile attempt to estimate this number, was make a list of all the places I’ve been that might be photography hot-spots. I live in New York City, so that’s one big place for photographs. And I’ve been to six of what TripAdvisor calls the “top 50 tourist attractions in the world.”

But how many photos are taken at each of those places? That’s hard to figure out too. Google has a site called Panaramio, a mashup of photo sharing and geo-tagging. And a site called Sitesmap shows how many photos have been uploaded to Panaramio in each location. But these are just photos that have been shared using Panaramio, which isn’t a particularly popular service. Looking at a single photo-sharing service like Flickr could give one sense, but it would be a small slice of the photographic pie. And on many social sites, geotags aren’t easily searchable.

Then there’s the question of whether any of this matters. Right now there are some number of photographs that include me in the background. So what?

“It’s like that thing about the tree falling in the forest,” Schoenebeck says “It’s so easy to take and delete digital photos, and you may not know they exist, you may never know they existed, what does that mean for your own digital identity? Does it even matter?”

Martin Hand, a sociologist at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada, has the same question. “Unless you’ve got a tag, you’re not going to know you’re in it, unless you stumble across it. There are these ghost profiles floating around, sort of ephemeral versions of you that you’re unaware of. They’re kind of like wallpaper.”

Schoenebeck studies how parents and teens relate to digital photos—she looks at things like moms posting baby-photos online, and how teenagers feel about their earlier selves immortalized in digital images on Facebook. She and Hand both talked about how teens today take a lot of care in the photos they post. Instead of dumping all 30 photos they took at the Eiffel Tower into a Facebook album, they’ll post two. Their relationship with photos isn’t one of personal memory, but rather of public identity. Hand describes the thinking: “Of course you take images in order to distribute them, that’s what they’re for.”

In the past, technological constraints required careful decision making on the front-end of the photo-taking process: With only a couple-dozen photos on a roll of film, you had to be deliberate about when and what to shoot. Today, technological advances allow a kind of reverse. Smartphones and digital cameras mean a person can take hundreds, even thousands, of photos all at once. People used to post all those photos online, in massive Flickr or Facebook albums. Now, they’re more selective. But in both cases, the deliberation comes after you’ve taken them.

There are, out there in the world, photographs in which your appearance is incidental, on the side, perhaps not looking the way you want to look. That’s been true since long before the Internet came along. But online programs have introduced new wrinkles.

Consider Google’s imagery, for example. There are Google cars winding their way through the streets, capturing the convergence of people and places in time. This surveillance can lead to astonishing outcomes. There are several stories of people finding images of their parents, now dead, captured by the Google Street View cars. “Before my father died, Google cameras captured him—healthy and happy—tending his yard,” wrote Bill Frankel in a story for Modern Loss. “For years after his death, I visited him frequently in cyberspace.”

The Guardian runs a photography series called “That’s me in the picture,” where they resurface images from old news stories and find the folks in them. Brigitte Kleinekathöfer was photographed in Essen, West Germany, in 1985 as part of a photography project that compared life on either side of the Berlin Wall. Carol Cuffe was captured at a Beatles concert in 1963. People often enjoy reliving moments captured on film, and published in newspapers years ago.

Other times, it’s not so positive. There are also several stories of cheaters being caught by the Google cameras. Or drunk people puking or passed out in a lawn, or drug deals in action, or a painful-looking tumble off a bicycle. But these images are ostensibly anonymous. Google blurs the faces of people it capture, and the only reason you’d come across one is if you were perusing Google Street View. But faces soon aren’t going to be necessary for a place like Facebook to tag you.

When Google+ first launched, I started getting strange notifications. The site would show me an image, and ask something like, “is this you?” I remember a few of them, images of family dinners, parties, smiling people. But they were never me. “No,” I told Google+, those aren’t me. And eventually it stopped asking. I’m just waiting for the day it starts to ask again, and when it does, it’s really me somewhere in those pictures.