What Makes a Country Legalize Abortion?

The political science of a volatile issue—and why Ireland could be next

What leads a country to legalize abortion? What’s the tipping point?

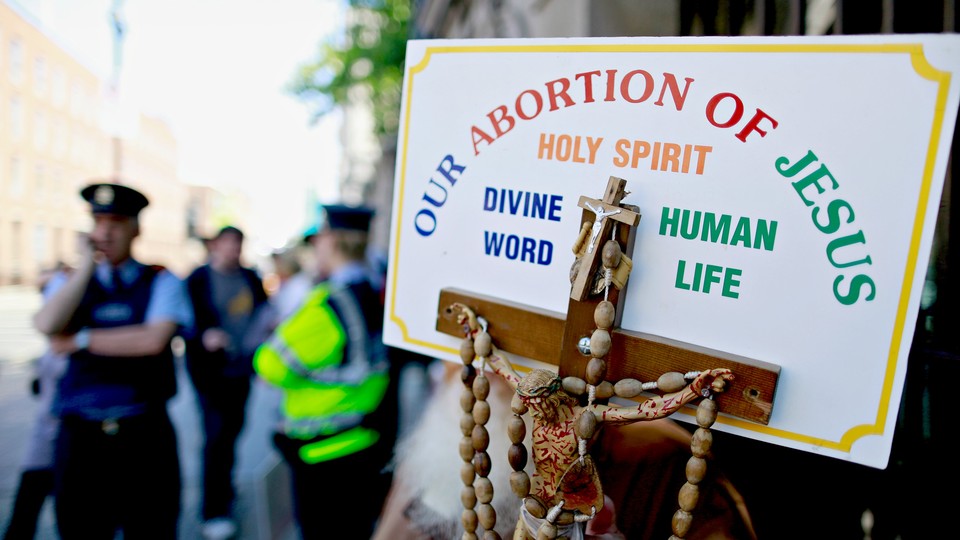

It’s a pertinent question now that a debate over abortion policy is ramping up in Ireland, ahead of an election there this spring. Since the 2012 case of a mother dying after being denied a termination for a miscarriage in progress, the near-absolute ban on abortion in the predominantly Catholic country has come under increased scrutiny. In 2013, a law was passed stipulating that an exception allowing abortions in cases of threat to the mother’s life should include situations in which the mother is suicidal. Last December, Ireland’s high court ruled that a brain-dead woman who was 18 weeks pregnant could be removed from life support, instead of kept alive for a Cesarean delivery.

This summer, a poll by Amnesty International found that 81 percent of respondents in Ireland supported “significantly widening the grounds for legal abortion access,” whether for rape cases, fetal abnormalities, or some other condition. And some polls suggest the number has been that high for years. In the past year, reproductive-rights groups, prominent Irish artists, several Irish politicians, and even the actor Liam Neeson have called for a referendum to repeal the Eighth Amendment of Ireland’s constitution, which was adopted following a similar referendum in 1983. The amendment enshrines a commitment to the “right to life of the unborn,” albeit “with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother,” translating to abortion only being permitted where the life of the mother is clearly at risk. The painter Eithne Jordan, a signatory of a petition from hundreds of Irish artists to abolish the amendment, told The Irish Times that the group has no particular vision for the conditions under which abortion should be legal: “We are not lawyers, we are not doctors. But I think [the amendment] definitely has to be repealed before a real conversation happens.”

If the vast majority of the electorate wants change, why is that change taking so long to materialize?

In fact, this kind of political paradox is not unusual. It has to do with the unique position abortion occupies in the realm of public opinion, according to the Temple University political-science professor Kevin Arceneaux.

One of the remarkable lessons about abortion gleaned from the United States, said Arceneaux, is that unlike other divisive social issues such as gay marriage (which Ireland legalized via referendum in May), “when you look at public-opinion polls there’s not been that much movement over time.” In the U.S., “if you ask people specifics about the circumstances under which abortion can happen you will see some differences. But if you just want to ask the question in general—‘Is this a moral thing?’—on that I think opinions have been pretty stable.” This has to do, he said, with the extent to which abortion is a visceral issue, involving a person’s intuition about what constitutes taking a life.

These gut feelings also mean that the wheeling and dealing politicians typically employ on other policy issues doesn’t work when it comes to abortion. Theoretically, Arceneaux observed, “you could have a party that had more people in it that were opposed to abortion but maybe they’re indifferent about it in some respects or there are other things they care way more about. The party could then logroll on that issue. They could say, ‘Well, the Labor Party really cares about abortion. Our voters don’t really care about abortion but they care about tax policy. We’ll give the Labor Party what they want on abortion and we’ll get what we want on tax policy.’”

But abortion isn’t tax policy. “The problem with abortion is that it’s a very difficult issue to logroll on. It’s difficult to compromise on,” Arceneaux said. Some policies with less public support than legalizing abortion may become law through ordinary political give-and-take, but abortion rights are not the type of thing to be legislated quietly. Which means that however much abortion might seem like a religious issue similar to gay marriage, the discourse about it winds up being more like the U.S. gun-control debate. “Organized interests play an outsized role,” because when you can’t do much to change minds, you need to mobilize the voters for whom this is the deciding factor in which candidate they vote for. In other words, you play to priorities.

“If you’re a politician, it would be suicide in many [U.S.] districts to support any gun-control legislation. You only need 10 to 15 percent of the district to say, ‘I’m going to vote for anybody else but you because of that,’” Arceneaux noted. Changing a public-opinion poll by 5 percent generally doesn’t matter much. Finding 5 percent of the electorate who will show up to the polls every time, and vote on a given issue every time, does.

In the United States, abortion was legalized through a court decision—a relatively rare occurrence among Western countries. In the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Italy, to name just a few examples, abortion has been legalized primarily through legislation, although in Germany and Italy judicial rulings on cases that showed a lack of clarity in existing law have provided the impetus for change.

What factors are behind these decisions to legalize abortion? One dynamic that appears repeatedly in political-science research is the role of special-interest groups and particularly, although not exclusively, the strength of a country’s women’s rights movement. Reviewing the paths to abortion liberalization in Europe in a study this past year, the German political scientists Kerstin Nebel and Steffen Hurka concluded that public advocacy by women’s movements, in addition to “women vot[ing] with their feet, travelling to other countries where abortions were legal, or alternatively obtaining their abortion illegally in their home country,” were frequently decisive—not least because women obtaining abortions one way or another “in turn activated the courts, which increasingly found themselves under pressure to clarify the legal situation,” which in turn “paved the way for governments (and more importantly parliaments) to reform their countries’ abortion laws, which were considered hopelessly outdated.” But additionally, a country’s specific political system could exert a profound influence on how quickly pressure resulted in change.

In Ireland’s case, the structure of political parties and special interests might make it more resistant to change in this area than other countries are. In a 1992 paper, the University of Essex government professor Vicky Randall laid out a number of ways that the politics of abortion in Ireland have been unique among European countries. While left-wing parties elsewhere in Europe have tended to channel support for abortion reform into a broader interest group with political clout, Ireland’s left-wing parties have historically been fairly weak—in part because, when they were founded, their identities had more to do with the extent of their nationalism, rather than some working-class or socialist platform that would provide the basis for strong identity politics going forward. And while medical doctors have tended to lead the charge for decriminalizing abortion in the United States and Europe, in Ireland, “prominent members of the medical elite led the Pro-Life Amendment Campaign.” Ireland’s feminist movement got a late start, and just didn’t have the firepower to push for abortion liberalization in an organized fashion that would translate into votes.

Nor was the feminist movement maneuvering what guns it had into battle formation, according to Evelyn Mahon, a researcher at Trinity College Dublin’s School of Social Work and Social Policy. Looking in 2001 at how Ireland differed from other European states, she pointed out that “abortion has been a marginal rather than a central feature of the women’s movement,” which tended to focus on “generat[ing] empathy and understanding for women who have abortions” rather than legislative lobbying. “Demands for abortion law reform have divided rather than unified the movement,” she wrote.

Activists in Ireland aren’t as pessimistic about changing minds as political scientists might be. “For so long,” said Janet Ní Shuilleabhían, a spokesperson for the Abortion Rights Campaign, “health care and reproductive care were something that wasn’t spoken about. So terminations, people coming forward talking about having to travel for terminations—the idea that somebody would want an abortion, ask for an abortion has really been quite radical in this country.” (Reproductive-rights groups estimate that around 5,000 women in Ireland travel abroad each year for abortions.) Ní Shuilleabhían thinks that as information spreads, opinions might change.

Other campaigners point to ignorance about the current abortion law as further evidence that minds can be changed. The Amnesty International poll in August showed that not even one in 10 respondents were “aware of the correct criminal penalty for abortion when the life of the mother is not at risk [up to 14 years in prison], with two thirds unaware that it carries any criminal penalty.” Once informed of the legal penalty, nearly nine in 10 thought it was unreasonable. Sixty percent said they strongly agreed that abortion should be decriminalized, with an additional 7 percent saying they slightly agreed.

But does “strongly agreed” mean “I will vote on it”? Even if abortion policy turns out not to be a major factor in the election results, the recent work of abortion-rights groups could still have an impact, just not quite in the way they think: De-stigmatizing the discussion of abortion issues could lead to more court cases, which could in turn put pressure on politicians to make the law more consistent and enforceable. In spite of the 2013 law permitting abortion for suicidal mothers, an immigrant woman last year was denied an abortion eight weeks into her pregnancy even after being diagnosed as suicidal, and was forced by court order to undergo a Cesarean section at 25 weeks once she went on a hunger strike. That’s the sort of story that could push lawmakers to rethink abortion policy, if only for the sake of clarity. Equally, the more uncertain the law seems to be, the more doctors and health-care providers may push for reform. As one Irish obstetrician told Amnesty International in June, “Under the [current law] we must wait until women become sick enough before we can intervene. How close to death do you have to be? There is no answer to that.”