Hillary Clinton Goes Back to the Dunning School

How do you diagnose the problem of racism in America without understanding its actual history?

Last night Hillary Clinton was asked what president inspired her the most. She offered up Abraham Lincoln, gave a boilerplate reason why, and then said this:

You know, he was willing to reconcile and forgive. And I don't know what our country might have been like had he not been murdered, but I bet that it might have been a little less rancorous, a little more forgiving and tolerant, that might possibly have brought people back together more quickly.

But instead, you know, we had Reconstruction, we had the re-instigation of segregation and Jim Crow. We had people in the South feeling totally discouraged and defiant. So, I really do believe he could have very well put us on a different path.

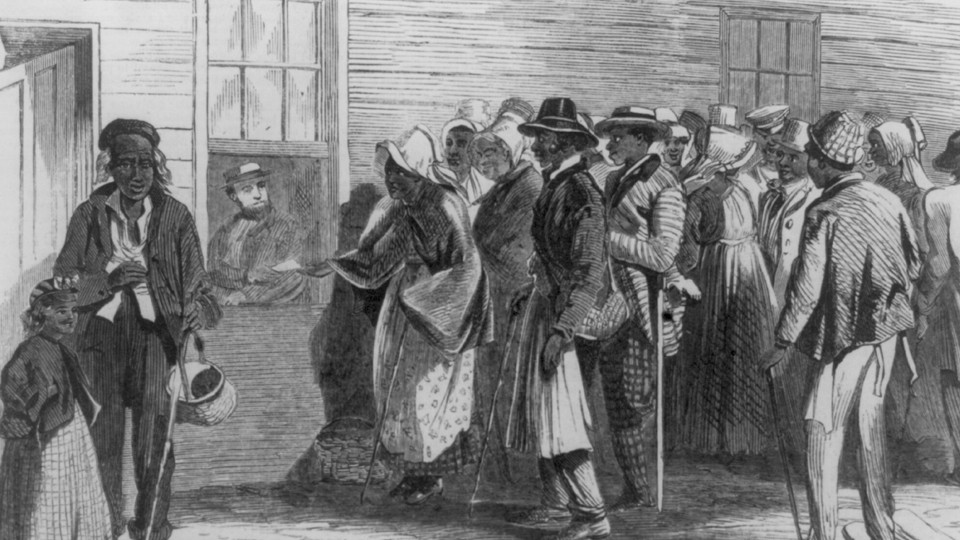

Clinton, whether she knows it or not, is retelling a racist—though popular—version of American history which held sway in this country until relatively recently. Sometimes going under the handle of “The Dunning School,” and other times going under the “Lost Cause” label, the basic idea is that Reconstruction was a mistake brought about by vengeful Northern radicals. The result was a savage and corrupt government which in turn left former Confederates, as Clinton puts, it “discouraged and defiant.”

A sample of the genre is offered here by historian Ulrich Phillips:

Lincoln in his plan of reconstruction had shown unexpected magnanimity; the Republican party, discarding that obnoxious name, had officially styled itself merely Unionist; and the Northern Democrats, although outvoted, were still a friendly force to be reckoned upon … With Johnson then on Lincoln's path “back to normalcy”, Southern hearts were lightened only to sink again when radicals in Congress, calling themselves Republicans once more, overslaughed the Presidential programme and set events in train which seemed to make "the Africanization of the South" inescapable. To most of the whites, doubtless, the prospect showed no gleam of hope.

Notably absent from it is the fact that Lincoln was killed by a white supremacist, that Johnson was a white supremacist who tried to curtail virtually all rights black people enjoyed, that the “hope” of white Southerners lay in the pillage of black labor, that this was accomplished through a century-long campaign of domestic terrorism, and that for most of that history the federal government looked the other way, while state and local governments were complicit.

Yet until relatively recently, this self-serving version of history was dominant. It is almost certainly the version fed to Hillary Clinton during her school years, and possibly even as a college student. Hillary Clinton is no longer a college student. And the fact that a presidential candidate would imply that Jim Crow and Reconstruction were equal, that the era of lynching and white supremacist violence would have been prevented had that same violence not killed Lincoln, and that the violence was simply the result of rancor, the absence of a forgiving spirit, and an understandably “discouraged” South is chilling.

I have spent the past two years somewhat concerned about the effects of national amnesia, largely because I believe that a problem can not be effectively treated without being effectively diagnosed. I don’t know how you diagnose the problem of racism in America without understanding the actual history. In the Democratic Party, there is, on the one hand, a candidate who seems comfortable doling out the kind of myths that undergirded racist violence. And on the other is a candidate who seems uncomfortable asking whether the history of racist violence, in and of itself, is worthy of confrontation.

These are options for a party of amnesiacs, for people whose politics are premised on forgetting. This is not a brief for staying home, because such a thing doesn’t actually exist. In the American system of government, refusing to vote for the less-than-ideal is a vote for something much worse. Even when you don’t choose, you choose. But you can choose with your skepticism fully intact. You can choose in full awareness of the insufficiency of your options, without elevating those who would have us forget into prophets. You can choose and still push, demanding more. It really isn’t too much to say, if you’re going to govern a country, you should know its history.