‘Segregation Had to Be Invented’

During the late 19th century, blacks and whites in the South lived closer together than they do today.

CHARLOTTE, N.C.—Growing up here in the 1940s and 1950s, Sevone Rhynes experienced segregation every day. He couldn’t visit the public library near his house, but instead had to travel to the “colored” library in the historically black area of Brooklyn, a neighborhood that used to be in the center of Charlotte. He attended a school for black children, where he received second-hand books, and where the school day was half the length of that of white schools, because the black school had too many children and not enough funds. Sixty years later, he says, Charlotte is still a segregated city. “People who are white want as little to do with black people as they can get away with,” he told me.

This is, unfortunately, not a surprising account of North Carolina, or of the South more generally. The South of the 1950s was the land of fire hoses aimed at black people who dared protest Jim Crow laws. Today, schools in the South are almost as segregated as they were when Sevone Rhymes was a child. Southern cities including Charlotte are facing racial tensions over the shootings of black men by white policemen, which, in Charlotte’s case, led to massive protests and riots.

But what few people know is that the South wasn’t always so segregated. During a brief window of time between the end of the Civil War and the turn of the 20th century, black and white people lived next to each other in Southern cities, creating what the historian Tom Hanchett describes as a “salt-and-pepper” pattern. They were not integrated in a meaningful sense: Divisions existed, but “in a lot of Southern cities, segregation hadn’t been fully imposed—there were neighborhoods where blacks and whites were living nearby,” said Eric Foner, a Columbia historian and expert on Reconstruction. Walk around in the Atlanta or the Charlotte of the late 1800s, and you might see black people in restaurants, hotels, the theater, Foner said. Two decades later, such things were not allowed.

As Hanchett, the author of Sorting the New South City: Race, Class, and Urban Development in Charlotte, 1875-1975, puts it, “Segregation had to be invented.”

This amorphous period of race relations in the South was first described by the historian C. Vann Woodward, who wrote in his 1955 book, The Strange Career of Jim Crow, that segregation in the South did not become rigid with the end of slavery, but instead, around the turn of the century. “There occurred an era of experiment and variety in race relations of the South in which segregation was not the invariable rule,” he wrote.

During that time, Foner said, black residents could could sue companies for discriminating against them—and win their lawsuits. Blacks could also legally vote in most places (disenfranchisement laws did not arrive in earnest until about 1900), and were often allied with poor whites in the voting booth. This alliance was strong enough to control states like North Carolina, Alabama, and Virginia at various points throughout the late 19th century.

This alliance was doomed. White elites, cast out of power and facing policies that threatened their economic hold on the state, launched a campaign that they knew would drive black and whites apart. They called it a campaign of “white supremacy,” and sought to unite whites of all economic backgrounds in hatred of black people. It was this campaign that tried to re-enforce the idea of black people as different, as lesser, and as a race that had to be separate from whites. Segregation was created in the South during this time period, and many of the ideas that drove it still exist more than a century later in the South of today.

College Street runs through the heart of Charlotte’s downtown, passing by skyscrapers like the Bank of America Corporate Center, fancy hotels like the Hilton, and the concrete and glass of the Charlotte Convention Center. The street has grown quite a bit since the 1870s, when it was comprised of small homes and businesses right on top of each other, according to Hanchett, who went through city rolls, which list residents’ occupation, race, and address. Neighborhoods were not divided by class—business owners lived next door to workers—or by race—blacks and whites lived on the same block, he found. On the College Street of 1877, for example, the black renter Ben Smith lived next to white bookkeeper Thomas Tiddy and white cotton merchant T.H. McGill. “More than a decade after the Civil War, Charlotte had no hard-edged black neighborhoods,” Hanchett writes, in his book. “Rather, African-Americans continued to live all over the city, usually side-by-side with whites.”

In fact, Hanchett says, it wasn’t immediately clear after the Civil War that race would necessarily be the biggest dividing line in America. The America of the late 19th century was, after all, a country in which social class and family history still played a big role in people’s fates. As the Charlotte Chronicle, a newspaper predominantly for white readers, wrote in 1887, wealth and position erected barriers “more despotic, if anything, than those based on prejudices of color.”

In the 1890s, an economic depression spread through the country, and white and black farmers and factory workers shared the belief that the pro-industry policies of the Democrats—usually elites who held land or owned businesses—weren’t serving them well. Black and white farmers were forced into sharecropping, which kept them mired in poverty. White workers in nascent factories were subject to terrible working conditions for low wages.

In 1894, black Republicans and white Populists joined together to create a “fusion” ticket of candidates to oppose Democrats. They shocked the political establishment and won two-thirds of the legislature.

This wasn’t the first time whites and blacks had allied politically. In Virginia in the late 1870s, black and poor white voters formed the Readjuster Party, which worked together to overcome the power of white political elites. In North Carolina; they also worked together to write the Constitution of 1868, which mandated the creation and funding of a state system of public education.

Yet the Fusion Party proved to be more powerful than anyone had anticipated. In 1896, it gained even more seats and elected a Republican as governor of North Carolina after decades of Democratic rule. (Fusion tickets also gained power in other Southern states, but none to the extent of the ticket in North Carolina, according to James Leloudis, a professor of history at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.)

Fusion was a ticket of the working class, and the alliance soon began implementing policies that helped its supporters. They capped interest rates, increased public-school funding, and allowed symbols to be put on ballots to enfranchise people who could not read or write. Their policies were designed, in the words of one supporter, to protect “the liberty of the laboring people, both white and black,” according to Leloudis.

The white elite were threatened by these new policies, especially because Fusion had shifted the burden of taxation from individuals to corporations and railroads. Yet they had little connection with poor voters, and so had few ideas about how to address their economic concerns. Instead, they tried to convince poor whites that they should not associate with blacks in any way. Democrats began to talk of blacks as an “other,” warning of the dangers of miscegenation, portraying blacks as rapists who would come after white women.

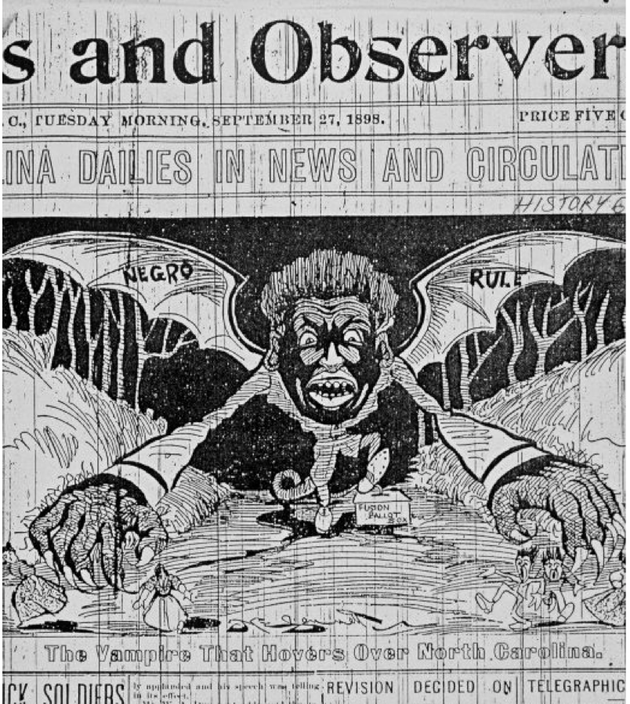

Democratic-controlled newspapers published cartoons about the horror of “Negro Rule” that had emerged from a Fusion ballot box, and stepped up coverage of black crime. “The Anglo Saxon Must Rule,” an editorial from the Charlotte Observer argued. A rising Democrat, Charles Aycock, gave speeches across the state urging Democrats “to unite the white people against the negroes, an infamous race,” according to Hanchett.

To ensure that they’d win in the elections of 1898, Democrats also resorted to physical intimidation. Their paramilitary arm, the Red Shirts, marched on black communities across North Carolina, disrupting black church services and Republican meetings.

The places they couldn’t win, they seized by violence. When the Red Shirts found out the Fusion ticket had won in Wilmington, North Carolina in the elections of 1898, a mob marched on town, killing black residents and forcing the mayor, board of aldermen, and police chief to resign at gunpoint. It was the only successful coup in American history.

Statewide, the white supremacy campaign was effective. In 1898, Democrats won 52.8 percent of the vote in North Carolina, and ousted many Fusionists from office. “Fusion Downed. The State Democratic. Whites to Rule,” The Charlotte Observer blared after the election.

Back in power, Democrats were determined to never lose power again. There were two ways of ensuring this, according to Leloudis: making sure blacks could no longer vote, and making poor whites feel superior to and animosity toward black voters.

In the 1899 legislative session, Democrats wrote an amendment to the state constitution that required that anyone who wanted to vote demonstrate to local elected officials that they could read and write any section of the Constitution. Voters ratified it in 1900, disenfranchising the state’s black voters for decades. Between 1890 and 1908, every state in the South adopted new state constitutions that sought to disenfranchise black voters. Democrats reigned in North Carolina and in the South for the next 60 years.

“The Democratic Party fought back, and said, ‘Look, the only way to stop this kind of thing is to take the vote away from black people,” Foner said.

The elite then set about normalizing imagined racial hierarchies, according to Leloudis. It was in 1899 that North Carolina passed its first Jim Crow law requiring separate seating for blacks and whites on all trains and steamboats. New regulations in Charlotte in 1899 required that blacks and whites be seated separately in courtrooms, and that separate Bibles be provided. In 1905, when Charlotte opened its first city-owned recreation ground, the local government passed a law stipulating that black people were not allowed inside. In 1907, North Carolina passed a law requiring segregated seating on all inter-urban trolleys in the state. Jim Crow laws were “a way of encouraging whites to see people of color as outcasts and pariahs,” Leloudis told me. They were a direct reaction to the short-lived political alliance between blacks and whites.

As whites were more and more encouraged to see blacks as the “other,” they increasingly lived in separate places, too. In 1876, for example, African Americans were scattered throughout the First Ward (the center of downtown) in Charlotte. Only three blocks of the ward were all black, according to Hanchett. By 1899, Charlotte’s First Ward blocks were mostly all black or all white, although those black and white blocks alternated and were close to one another. But between 1889 and 1910, segregation accelerated. What Hanchett calls “micro-segregation” gave way to patterns of sizable black and white clusters. Writes Hanchett: “In a topsy-turvy world, it might well be wise to put some physical distance between one’s own group and these others who could seem so strange. During the late 1880s to late 1920s, Charlotte leaders set to work to re-create their town in a modern urban image, abandoning old-fashioned salt-and-pepper intermingling in favor of a city sorted out into a patchwork quilt of separate neighborhoods for blue-collar whites, for blacks, and for the ‘better classes.’”

Charlotte today is an extremely segregated city. Whites largely live in a triangle in the city’s south, between South Boulevard and Providence Road, where neighborhoods are between 80 and 95 percent white. “Drive down our street, just about everyone is white,” Jimmy Carr, a white resident of that triangle, told me.

Blacks and the city’s growing Latino community live everywhere else. Census tracts in the north and west parts of the city are 70 percent black or more. And 43 of the 51 tracts that are 70 percent or more black or Hispanic are high poverty, according to 2014 Census data.

This segregation has proven an increasingly uncomfortable fact for a city that prided itself on racial harmony in the 1990s, as my colleague David Graham has written. In September, the city experienced demonstrations and riots after a police officer shot black resident Keith Lamont Scott.

And the city has been reckoning with damning data from the economist Raj Chetty that suggests that poor children in Charlotte have a worse shot at economic mobility than do poor children in 49 of America’s largest metro areas. Segregation plays a central role in that.

Of course, it wasn’t just the nasty politics of the early 1900s that made Charlotte into the segregated city it is today. Redlining in the 1930s made it difficult for black homeowners to get loans to buy or repair their homes. Federal highway construction in the 1960s and 1970s decimated traditionally black neighborhoods and displaced whole communities to the outer edges of town (including the neighborhood where former transportation secretary Anthony Foxx grew up). Gentrification continues to displace black and Latino Charlotte residents from neighborhoods where they had long lived.

But the policies that continue to segregate Charlotte and other Southern cities have their roots in the nasty racial battles of the late 19th century. To segregate residents, there had to first be an idea that white people were superior and that black people deserved less. That idea was a strategy pushed by elite whites to make sure they could hold onto power. It took hold and has never lost its grip.