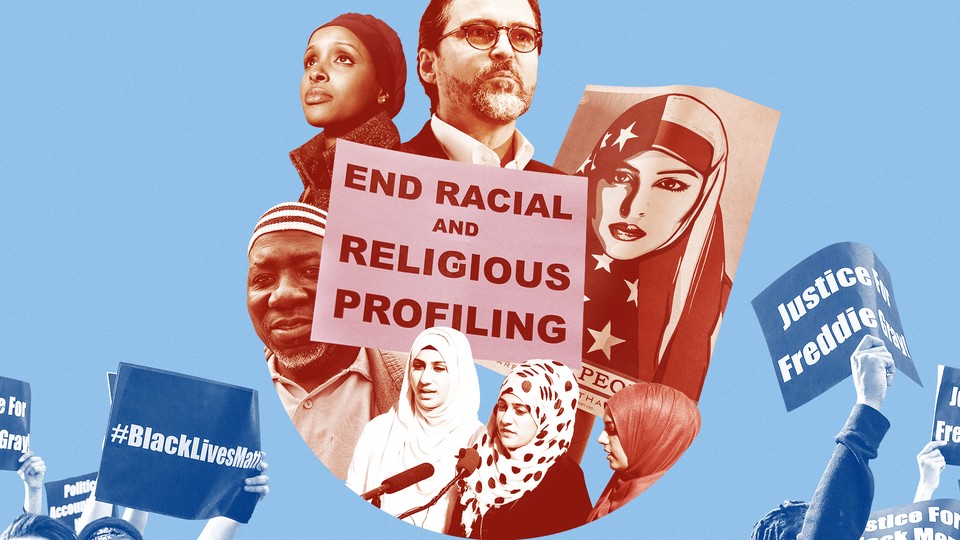

Muslim Americans Are United by Trump—and Divided by Race

Facing increasing hostility from the administration, the religious community also has to cope with its own internal tensions.

When weary Muslims gathered in Toronto in December for an annual retreat, marking the end of a tumultuous U.S. election year, they probably didn’t expect the event to turn into a referendum on racial tensions within the American Muslim community. But it did.

One session was led by Hamza Yusuf, a well respected white scholar who co-founded Zaytuna College, which claims to be America’s first Muslim liberal-arts college. At the end, he was asked whether Muslims should work with groups like Black Lives Matter. “The United States is probably, in terms of its laws, one of the least racist societies in the world,” he replied. “We have between 15,000 and 18,000 homicides per year. Fifty percent are black-on-black crime, literally. … There are twice as many whites that have been shot by police, but nobody ever shows those videos.”

He went on. “It’s the assumption that the police are racist. It’s not always the case,” he said. “Any police now that shoots a black is immediately considered a racist.”

The backlash on social media was swift and immense. “For black Muslims, hearing this from somebody we’ve all come to love and trust—it was a cold slap in the face,” said Ubaydullah Evans, the executive director of the American Learning Institute for Muslims, who is black. He said he saw Yusuf’s comments as a way of perpetuating myths about “black pathology” and blaming African Americans for violence. Yusuf’s statements were indeed somewhat misleading: While a greater number of white people have been shot by the police compared to black people, that statistic doesn’t account for population size. When that adjustment is made, historical data shows that black people are more likely to be shot by police than white people.

Even though slightly less than one-third of American Muslims are black, according to Pew Research Center, American Muslims are most often represented in the media as Arab or South Asian immigrants. The distinction between the African-American Muslim experience and that of their immigrant co-religionists has long been a source of racial tension in the Muslim community, but since the election, things have gotten both better and worse. While some Muslims seem to be paying more attention to racism because of Donald Trump, others fear that any sign of internal division is dangerous for Muslims in a time of increased hostility.

While the Toronto conference was upsetting, Evans said, he doesn’t think it’s representative of the biggest racial problems in the American Muslim community. White racism toward black people is “not the kind of racism that circumscribes my life as an American Muslim,” he told me. “It’s the social racism I experience from people of Arab descent, of Southeast Asian descent. This is the racism no one is talking about.”

The wave of immigration that shaped today’s American Muslim population began in the 1960s, after Congress lifted previous race-based restrictions on immigration. In many ways, this surge was directly connected to the work of black Muslims and others involved in the civil-rights movement: The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 allowed far greater numbers of people from Asia and Africa to emigrate to the U.S. As of 2014, an estimated 61 percent of Muslims were immigrants, according to Pew, and another 17 percent were the children of immigrants. Many of the perceived racial tensions among Muslims come from conflicts between these immigrant communities and non-immigrants, who are often black.

“Immigrant Muslims had a convenient comfort zone,” said Omar Suleiman, an imam based in Dallas who serves as president of the Yaqeen Institute for Islamic Research. As each new immigrant community established its own mosques and community centers, portions of the Muslim American population became segregated by ethnicity and income. For non-black Muslims who grew up in the suburbs, attended private schools, and rarely encountered black Muslims in their mosques, it’s easy “to internalize many of the poisonous notions about the black community that … diminish the pain of those communities,” he said.

“I think a lot of African American Muslims see a hypocrisy sometimes with immigrant Muslims,” said Saba Maroof, a Muslim psychiatrist with a South Asian background who lives in Michigan. “We say that Muslims are all equal in the eyes of God, that racism doesn’t exist in Islam.” And yet, cases of overt racism aren’t uncommon, like when South Asian or Arab immigrant parents don’t want their kids to marry black Muslims. “That happened in my family,” she said.

These stereotypes are sometimes perpetuated by leaders like Yusuf. Toward the end of the Toronto conference, he apologized for the ambiguity of his previous comments, but clarified that he believes “the biggest crisis facing the African American community in the United States is not racism. It is the breakdown of the black family.” The line won huge applause in the presentation hall where Yusuf was speaking. But online, there was yet more backlash: Kameelah Rashad, a black Muslim chaplain at the University of Pennsylvania, started tweeting out pictures under the hashtag #blackMuslimfamily, for example, to protest Yusuf’s remarks. (Yusuf declined a request for an interview.)

Some Muslims believe “we shouldn’t talk about anti-blackness within the community, because we’re under siege by Islamophobes. This is not the right time to air internal laundry,” Rashad said. But “if I have to contend with anti-Muslim bigotry outside of the Muslim community, and within my own community, I’m having to push back on anti-black racism, I’m kind of fighting a war on two fronts.”

Racial dynamics have long shaped Muslims’ political identities. There’s a “tendency to regard issues that impact black people—and by extension, black Muslims—as not thoroughly Islamic,” said Evans. “If we’re talking about a social issue in Palestine or Chechnya or Kashmir or Saudi Arabia or anywhere else, those things can properly be engaged as ‘Islamic issues.’ [If] we’re talk about economic injustice, or gentrification, or ex-offender re-entry, or recidivism, those things aren’t really regarded as ‘legitimately Islamic.’ It’s like, ‘Why would a Muslim of conscience be talking about that stuff?’”

As Muslim leaders have taken up visible roles in anti-Trump activism, these dynamics have intensified. Progressive leaders have condemned the so-called Muslim ban—the executive order that originally affected people from seven Muslim-majority countries—putting the focus in the Muslim community on immigration. But when protesters swarmed airports in large American cities following the order’s release, some black Muslims stayed home, said Margari Hill, the co-founder of the Muslim Anti-Racism Collaborative, who is also a black Muslim. “They have this long-term struggle. Not much has changed—it’s always been kind of terrible,” she said. And “when it comes to the spectacle of black death, we don’t necessarily see a lot of Middle Eastern or South Asian Muslims showing up for Black Lives Matter.”

In activist spaces, black Muslim leaders are sometimes discounted as well. “We’re often questioned, undermined, and asked to bring other experts as the voice of authority,” said Asha Noor, the former leader of an anti-Islamophobia campaign called Take on Hate, who is a Somali-American Muslim. “I’ve seen a lot of black Muslims retreat into our own spaces because they are safe spaces for us.”

As American Muslims have dealt with everything from arson to assault because of their religious identity over the past several months, leaders have increasingly called for unity. But attempts to unify can also stifle diversity, said Hill. Even though three of the seven countries originally included in Trump’s immigration order are in Africa—Libya, Sudan, and Somalia—Hill said she rarely sees people from those countries featured in the news. Instead, media outlets typically go for “people who are ethnic, but not too much,” she said. “You have to be a little attractive.”

There’s also debate within the community on the right way for Muslims to show their patriotism. The red, white, and blue hijabi was a visible symbol in the Women’s March on Washington in January, but not all Muslims think that image sends the right kind of message about the religion. “It feels like a performance,” said Rashad. “As a black American, I am fully cognizant of the fact that that kind of performance does not lead to equality.” While Muslim immigrants have often viewed America as a meritocracy, she said, “For black Muslims, our history is complicated. This hasn’t been a place of opportunity or meritocracy.”

Despite these tensions, Trump’s election has inadvertently prompted some new conversations about race among Muslims. Maroof compared Muslims’ new interest in race to a recent skit on Saturday Night Live: A room full of white people watching the 2016 election results start to realize America has issues with racism, while their black friends just nod along. After the election, Maroof started a book club to learn more about political activism, and asked Rashad, who also works in mental health, for recommendations. She suggested The New Jim Crow, a book about racism and mass incarceration. “The awakening I see some non-black Muslims experiencing is very similar to some of the awakening I’ve seen my white friends going through,” Rashad said.

Maroof said she has been aware of racial tensions among Muslims for a long time, but feels like it’s particularly important to pay attention to these issues now. “Even after 9/11, it wasn’t this bad. There was not this travel ban or things like that,” she said. But she recognizes that for a lot of Muslims—herself included—starting conversations about intra-Muslim racism will inevitably come with uncomfortable moments. “Maybe people are sometimes afraid they’re going to say the wrong thing,” she said. “Nobody wants to be known as a racist.”

Meanwhile, some black Muslims are having a political awakening of their own on issues like immigration. “There wasn’t as much outrage with the Obama administration,” said Hill. Obama used less inflammatory rhetoric to talk about immigration, but his administration still removed a record-number of undocumented immigrants from the United States. “Things that were invisible to many of us who have privilege as non-immigrants—now we see it,” she said.

The irony of Islamophobia is that it may eventually produce the exact cultural effect Islamophobes fear: Muslim Americans may find a newly consolidated sense of identity and unity because of their religious affiliation. If some Muslims once hoped to be fully assimilated into elite American culture—to live in nice neighborhoods, attend fancy schools, and fully blend in with white America—that’s likely impossible now, Evans said. “The first blow to that aspiration was 9/11. Then ISIS happened. The prospect began to look even farther off,” he said. “With the Trump election, I really think it was finished off. It’s over now.”