The Dark Morality of Fairy-Tale Animal Brides

Beauty and the Beast, a new collection of folk stories from around the world, explores the strangeness of interspecies relationships.

It’s easy to forget—amid the kicky tap-dancing kitchenware, the twinklingly romantic score, and the swooning waltz in both Disney versions—how strange the central concept of Beauty and the Beast is. Here, presented by the foremost corporate purveyor of children’s entertainment, is essentially a story about a woman who falls in love with an animal. In the 1991 cartoon, the animated Beast’s goofy facial expressions alleviate the weirdness of it all by making him convincingly human-ish (and so endearing that his actual princely form, as Janet Maslin wrote in her review of the first film, is actually a disappointment, a “paragon of bland handsomeness”). But in the 2017 live-action movie, the Beast is unabashedly ... beastlike. His blue eyes can’t quite conquer an ovine face crowned by a majestic lion’s mane and two disturbingly Freudian horns.

In the original version of the story “Beauty and the Beast,” though, published in 1740 by the French novelist Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve, the Beast seems to be an awful kind of elephant-fish hybrid. Encountering Beauty’s father for the first time, the Beast greets him fiercely by laying “upon his neck a kind of trunk,” and when the Beast moves, Beauty is aware of “the enormous weight of his body, the terrible clank of the scales.” But in the most famous adaptation, a version for children abridged by the former governess Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, the question of what the Beast looks like is left to the imagination. De Beaumont specifies only that he looks “dreadful,” and that Beauty trembles “at the sight of this horrible figure.” The Beast could resemble a water buffalo, or a bear, or a tiger; he could also be interpreted as just a plain old man, essentially kind at heart but extremely unfortunate to look at. That’s the point of the story.

De Beaumont published most of her stories in instructional manuals for children, incorporating strong moral lessons into the stories. She wasn’t the only one to do so. “Fairy tales do not become mythic,” Jack Zipes wrote in his 1983 book Fairy Tale as Myth/Myth as Fairy Tale, “unless they are in perfect accord with the underlying principles of how the male members of society seek to arrange object relations to satisfy their wants and needs.” Indeed, as Maria Tatar points out in the superb introduction to her new collection Beauty and the Beast: Classic Tales About Animal Brides and Grooms From Around the World, the story of Beauty and the Beast was meant for girls who would likely have their marriages arranged. Beauty is traded by her impoverished father for safety and material wealth, and sent to live with a terrifying stranger. De Beaumont’s story emphasizes the nobility in Beauty’s act of self-sacrifice, while bracing readers, Tatar explains, “for an alliance that required effacing their own desires and submitting to the will of a monster.”

But “Beauty and the Beast” is also a relatively modern addition to a canon that goes back thousands of years: stories of humans in love with animals. Tatar’s collection features examples from India, Iran, Norway, and Ireland; she includes stories of frog kings, bird princesses, dog brides, and muskrat husbands. Each story is basically an expression of anxiety about marriage and relationships—about the animalistic nature of sex, and the fundamental strangeness of men and women to each other. Some, like “Beauty and the Beast,” prescribe certain kinds of behavior, or warn against being vain or cruel. But many simply illustrate the basic human impulse—common across civilizations—to use stories to figure things out.

“Beauty and the Beast,” Tatar writes, is a love story about “the transformative power of empathy,” but a dark and weird one. Coded inside it are all kinds of cultural neuroses regarding the social and emotional structure of marriage: fear of the other, fear of leaving home, fear of changing oneself by forming a new partnership. De Beaumont’s story, Tatar explains, “reflects a desire to transform fairy tales from adult entertainment into parables of good behavior, vehicles for indoctrinating and enlightening children about the virtues of fine manners and good breeding.” Beauty’s physical charms are matched perfectly by her virtue and selflessness, which contrast in turn with her sisters’ vanity, greed, and wickedness.

When Beauty’s father leaves to meet his ship, newly arrived in port, he asks his daughters what they would like as gifts. Beauty’s sisters ask for clothes and other finery; Beauty, not wanting to trouble him—or to make her sisters look bad—asks for a single rose, which precipitates her fate. Her father is knocked off his horse and welcomed into a mysterious house devoid of people, where he’s fed and sheltered. In the morning he remembers to clip a rose for Beauty, but the impertinence of his action summons the Beast, who sentences him to death, but allows Beauty’s father to send one of his daughters to die in his place.

Beauty, naturally, sacrifices herself. “I would rather be devoured by that monster than die of the grief that your loss would cause me,” she tells her father. Her actions inform readers that to “save” their own families by entering into marriages is noble, while preparing them for the prospect of embarking on their own acts of self-sacrifice. “That the desire for wealth and upward mobility motivates parents to turn their daughters over to beasts points to the possibility that these tales mirror social practices of an earlier age,” Tatar writes. “Many an arranged marriage must have felt like being tethered to a monster.”

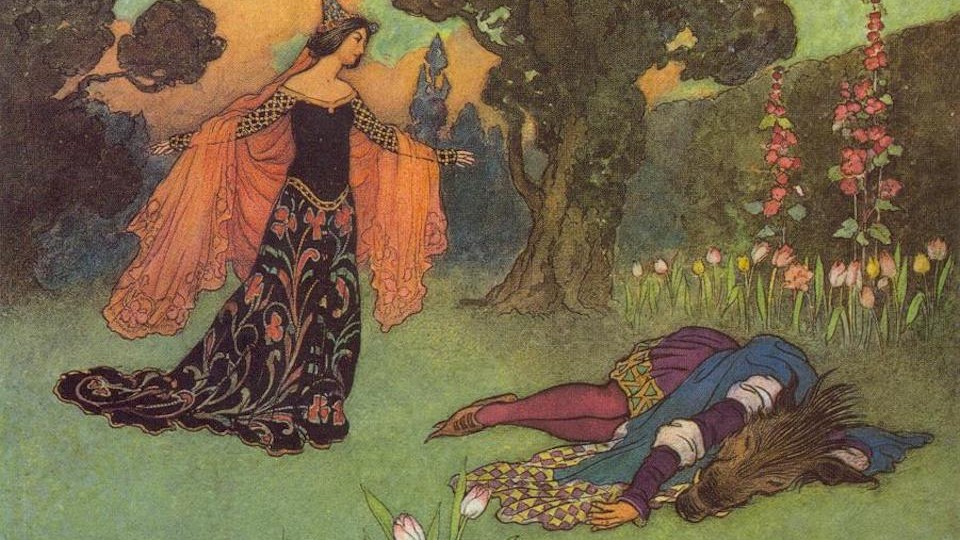

Like this one, many of the stories in Tatar’s anthology are “initiation myths”—tales that allegorize the various rituals of entering adulthood, whether by slaying dragons, traversing countries, or entering into contracts with strange and untrustworthy souls. In “Cupid and Psyche,” one of the earliest versions of the archetype, Psyche is told she must marry a monster, whom she is forbidden from seeing. At night, he makes love to her in darkness. But her sisters (also wicked busybodies) convince her to peek at him with the help of a lamp, at which moment she discovers that he’s actually Cupid, “the most beautiful and charming of the gods.” Her defiance of the rules, though, is catastrophic: Cupid disappears, and Psyche has to endure a number of impossible tasks to prove her worth to Venus, his domineering mother.

In a Ghanaian story, “Tale of the Girl and the Hyena-Man,” a young woman declares she won’t marry the husband her parents have chosen. She picks a stranger instead, “a fine young man of great strength and beauty.” Unfortunately, he turns out to be a hyena in disguise, who chases his wife as she transforms herself into a tree, then a pool of water, then a stone. The tale concludes succinctly: “The story of her adventures was told to all, and that is why to this day women do not choose husbands for themselves and also that is why children have learned to obey their elders who are wiser than they.”

As common as cautionary tales aimed at informing girls of the dangers of self-determination and the consequences of their unchecked curiosity are tales informing boys about the essential wildness of women. When brides are animals, they transform into efficient and dutiful housewives, but their animalistic nature remains within them. In “The Swan Maidens,” a hunter sees young women bathing in a lake after discarding their robes, which are made of feathers. He hides one of the dresses, which leaves one of the maidens stuck in human form, watching her sisters put on their swan robes and fly home. The hunter marries her and they have two children and live happily together, but when she finds her hidden feather-dress one day she immediately puts it on and reverts to her swanlike form, flying away and abandoning her family.

“The Swan Maidens” seems to speak to innate female desires, as well as a sense of loyalty and kinsmanship to one’s original tribe. It warns male readers about the potential alienness of women, who were long understood to be too close to nature, too feral. But it also illuminates what Tatar describes as “the secretly oppressive nature of marriage, with its attendant housekeeping and childrearing duties.” Animal brides make for excellent spouses when it comes to domestic tasks, but at a cost: They cannot be allowed the keys to their freedom.

So many of the primal and cautionary elements within fairy tales are addressed or subverted by Angela Carter in The Bloody Chamber, a 1979 collection of stories inspired by folk tales. In the title story, the heroine sells herself into marriage, ignoring her mother’s doubts; she later travels “away from Paris, away from girlhood, away from the white, enclosed quietude of my mother’s apartment into the unguessable country of marriage.” At the end of the journey lies a husband who is indeed a monster—not an animal but a serial murderer of women. The heroine is eventually saved not by a man but by her adventurous, brave, and nonconformist mother.

Carter writes, in her collection, of fathers who lose their daughters to beasts at cards, and of girls initiated into adulthood in farmyards, where they witness bulls and cows together. The trappings of fairytale morality suffuse her stories, but she refuses to hew to their conventions, instead having women transform themselves into beasts who match their partners in scenes of profound sexual awakening. In “The Tiger’s Bride,” the heroine is traded as “the cold, white meat of contract,” but she willingly abandons that vulnerable skin for a “beautiful fur” as she metamorphoses into the tiger’s equal.

In The Bloody Chamber, Carter writes her own, distinctly feminist fables, and proves that even the oldest storytelling models can be adapted to fit contemporary experiences and anxieties. But Tatar points out, too, that every generation of monsters speaks to the anxieties of its time. Stories about animal brides and grooms gave way in the 20th century, she writes, to stories about “beasts like King Kong and Godzilla, along with aliens from other planets”—modern manifestations of fears about the “other.” In part this was because the industrial revolution gave humans more distance from animals, making them a less powerful presence and source of anxiety.

In the 21st century, the stories we tell have been technologically upgraded, although they’re still following the model of the tales in Tatar’s collection. TV shows and movies are full of humans falling in love with elusive and untrustworthy robots, from Ex Machina to Westworld. In Spike Jonze’s 2013 movie Her, Theodore (Joaquin Phoenix) falls for a sentient operating system, Samantha (Scarlett Johansson), who eventually evolves beyond humans and abandons Theodore to explore her own capabilities. The ending of the film echoes the Swan Maiden leaving her husband behind as she reverts to her innate, alien form. And so the tradition continues to evolve. Robots, like beasts, represent the fear of difference, the challenge of connection, and the thrill of the unknown—as well as a host of new anxieties. “It may be a tale as old as time,” Tatar writes, “but it is never the same story.”