The American South Will Bear the Worst of Climate Change’s Costs

Global warming will intensify regional inequality in the United States, according to a revolutionary new economic assessment of the phenomenon.

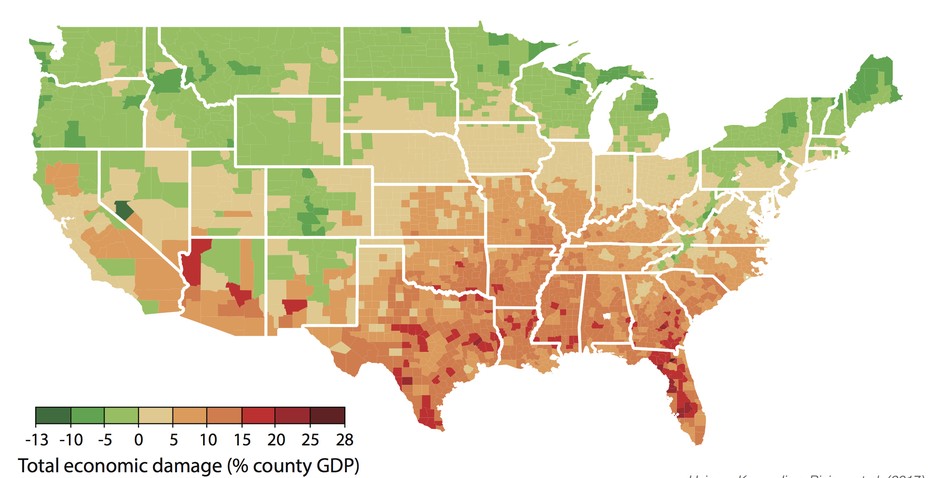

Climate change will aggravate economic inequality in the United States, essentially transferring wealth from poor counties in the Southeast and the Midwest to well-off communities in the Northeast and on the coasts, according to the most detailed economic assessment of the phenomenon ever conducted.

The study, published Thursday in Science, simulates the costs of global warming in excruciating detail, modeling every day of weather in every U.S. county during the 21st century. It finds enormous disparities in how rising temperatures will affect American communities: Texas, Florida, and the Deep South will bleed income in the broiling heat, while some chillier northern states gain moderate benefits.

“We are really sure the South is going to get hammered,” says Solomon Hsiang, one of the authors of the paper and a professor of public policy at the University of California, Berkeley. “The South is really, really negatively affected by climate change, much more so than the North. That wasn’t something we were expecting going in.”

Overall, the paper finds that climate change will cost the United States 1.2 percent of its GDP for every additional degree Celsius of warming, though that figure is somewhat uncertain. If global temperatures rise by four degrees Celsius by 2100—which is very roughly where the current terms of the Paris Agreement would put the planet—U.S. GDP could shrink anywhere between 1.6 and 5.6 percent.

Yet beyond its initial findings, the paper represents a major breakthrough for the field of climate economics. Previously, the best financial forecasts of climate change approximated damages for the entire country at once. This new study worked from the bottom up, building its model from dozens of microeconomic studies into how climate change is already affecting regional economies across the United States. Every algorithm in the model emerges from a previously observed relationship in real-world data.

“This is like the adults entering the room. Economists have, for a quarter century, insisted that more work needs to be done to estimate climate damages. This team has done so,” said Gernot Wagner, a researcher Harvard University and the former lead senior economist at the Environmental Defense Fund, in an email. He was not connected to the study.

But this emphasis on the observed means that the research omitted many serious risks of climate change—even those the researchers considered important—if the data describing them was too paltry. The estimates do not include “non-market goods” like the loss of biodiversity or natural splendor. In other words: Most people agree that dead polar bears have an economic cost, but there’s no consensus on how to approximate it.

The study also doesn’t account for the increased likelihood of “tail risks”—that is, unlikely events with catastrophic consequences. Many researchers believe that global warming will make social strife, mass migration, or global military calamity more likely, but those events are, by definition, hard to predict. The same goes for economic disaster prompted by the onset of a “mega-drought” or the rapid collapse of the Greenland ice sheet.

“When we had the Dust Bowl, we saw everyone clear out of the Midwest and flood labor markets in the urban centers on the coast,” said Hsiang. Nothing like this kind of internal migration is modeled in the Science study.

All in all, the study’s assessments should be interpreted as the most rigorous attempt ever to describe what global warming will cost the United States in a “normal” world. It describes an America that has retained a well-organized economy, held together as a political community, and benefitted from the ongoing general global peace that began 70 years ago.

Even in that harmonious world, climate change will make the United States pay.

Across the country’s southern half—and especially in states that border the Gulf of Mexico—climate change could impose the equivalent of a 20-percent tax on county-level income, according to the study. Harvests will dwindle, summer energy costs will soar, rising seas will erase real-estate holdings, and heatwaves will set off epidemics of cardiac and pulmonary disease.

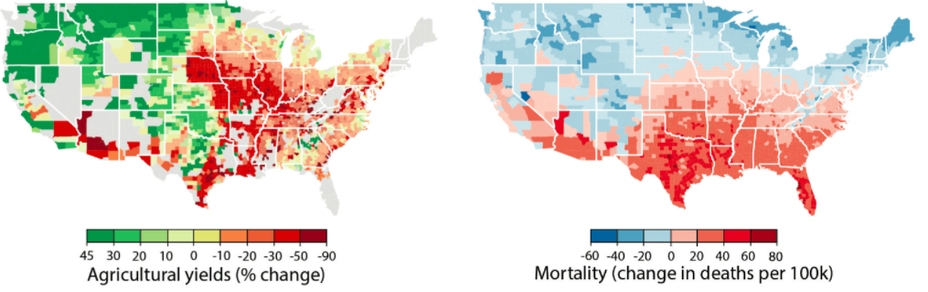

The loss of human life dwarfs all the other economic costs of climate change. Almost every county between El Paso, Texas, and Charlotte, North Carolina, could see their mortality rate rise by more than 20 people out of every 100,000. By comparison, car accidents killed about 11 Americans out of every 100,000 in 2015.

But in the South and Southwest, other damages stack up. Some counties in eastern Texas could see agricultural yields fall by more than 50 percent. West Texas and Arizona may see energy costs rise by 20 percent.

Simultaneously, the study finds that some regions may reap moderate economic benefits from global warming. New England, the Pacific Northwest, and the Great Lake states may all prosper as growing seasons lengthen, and the number of frigid, deadly winter days decrease. In the most optimistic scenarios, some counties could see their incomes rise by 10 percent by the middle of the century.

This may make some Americans scratch their heads. The high costs of climate change will fall on many of the places where people today seem least worried about the phenomenon.

“Most of the risk maps show that climate change is going to be terrible for Trump country. Like, it’s not clear at all—from these maps—why reducing climate change is not a more urgent issue for Republicans, purely as a matter of representing their people,” said Joseph Majkut, the director of climate policy at the Niskanen Center, a libertarian think tank, in an email. He was not connected to the study.

Hsiang explained the disparity as a consequence of the hot places getting hotter. “If you’re in a hot location already, then increasing the temperature tends to be much more damaging than if you’re somewhere that is cooler. Moving from 70 to 75 [degrees Fahrenheit] is not as big a deal as going from 90 to 95,” he told me. “The South, today, is already very hot. So as the country warms up, the South is disproportionately bearing the burden.”

In fact, the only factor of climate change that doesn’t specifically hurt the South is a projected rise in property crime associated with climate change. The incidence of nonviolent property crime doesn’t rise on summer days, but it tends to fall on the coldest days. “It’s hard to burgle houses or steal cars when there’s a lot of snow on the ground,” said Hsiang, laughing.

As the North’s winters get less icy, the region will see property-crime rates increase. But scorching summer days won’t alter the South’s crime rates. This is, however, a very small factor, Hsiang cautioned.

He also warned that the paper’s economic projections end in 2099. If climate change continues unabated into the 22nd century, the North will likely eventually “flip over” into much higher temperatures and more severe economic damages, Hsiang said.

The Science paper is the first product of the Climate Impact Lab, a 25-person consortium of economists and policy experts led by researchers from the University of California, the University of Chicago, Rutgers University, and the Rhodium Group. This study is the first part of their new global assessment of the economic costs of human-caused climate change.

“What has happened over the last 10 years is there’s been a revolution in our ability to measure the relationship between the climate and the economy, partly out of new, real-world data,” Hsiang told me. “This paper somewhat came out of the realization that all that new research wasn’t going anywhere. It wasn’t informing how we think about climate and the economy because those older models weren’t built in a way to absorb new findings.”

Their new program is called SEAGLAS. It’s designed to integrate new research into the regional and local effects of policy into a larger, holistic view of a certain country or part of the world. So while this study focused on U.S. county-level data about crime, human health, agriculture, labor supply, and energy demand, the researchers intend to fold new sectors and data sources into it in the future.

“It’s a great development, and the future of climate economics,” said Majkut. “This new study puts us on much more satisfying empirical ground as we consider the relationships between climate change and economic output. For that alone it should be praised.”

He did question one of the assumptions underlying the project: whether previously observed relationships will continue to hold in a future world. “If the high rates of human mortality can be eliminated or reduced with adaptation (more air conditioning, sports gels, better medicine, or people moving out of the South) then the economic picture really changes and the costs of climate will be reduced dramatically,” he said.

For that reason, Majkut said, “the research has a long way to go before it approaches anything like a comprehensive estimate of climate risk. Meanwhile, we emit.”

“SEAGLAS provides a terrific framework to build upon,” said Wagner in an email. “We’ve always known that there are enormous regional disparities across the globe. The fact that damages vary so much within a rich country like the U.S. is striking.”

So if climate modeling remains imperfect, what’s the point of doing it? Researchers have spent the last 25 years trying to forecast the economic damages of climate change. Eventually, they hope to arrive at the social cost of carbon—the damage to the economy dealt by every additional ton of carbon dioxide—which would inform the creation of a carbon tax. Yet across all those years, political opposition to a carbon tax has only hardened, and the amount of carbon in the atmosphere has only gone up.

Hsiang said that precision is still important. “If we have a rough number, is that good enough?” he asked. “I definitely think we’re never going to know the cost of climate change to seven decimal places. But it’s unclear what a rough number means, because there’s been very little benchmarking to any real-world data.” (An additional paper in this edition of Science clarifies that, so far, SEAGLAS has produced social costs of carbon that are fairly similar to two of the three most-famous economic climate models.)

“To be honest, transforming the global energy system is not a cheap task. It’s not a small thing,” Hsiang said. “And in some places, a lot of the concerns about implementing policy are related to concerns about the reliability of the numbers being used. It’s a little like the doctor coming in and saying you’re sick and he has some medicine which might work. You’ll feel much more comfortable about the medicine if you know there’s been clinical research and systematic control trials demonstrating it works.”