How Surrealism Enriches Storytelling About Women

The author Carmen Maria Machado, a finalist for this year’s National Book Award in Fiction, discusses the brilliance of an eerie passage from Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House.

By Heart is a series in which authors share and discuss their all-time favorite passages in literature. See entries from Colum McCann, George Saunders, Emma Donoghue, Michael Chabon, and more.

As she struggled to complete her debut collection, Her Body and Other Parties, Carmen Maria Machado worked retail at a bath-products store in Philadelphia. It was a difficult time, one that she described to me with an arresting turn of phrase: They wanted my head.

Machado’s not the first writer to chafe against a day job. But her formulation struck me in the way it made daily life’s encroachment on the imagination strangely physical, invasive, even violent. In a conversation for this series, Machado explained how Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House became a kind of call to arms, especially a scene where a little girl refuses an ordinary water glass—insisting instead on drinking from an adorned “cup of stars.” In part, the passage helps explain Machado’s refusal to adhere to the conventions of realism. But it’s more than that: It’s a reminder that the world will try to dull your capacity for magic, and we must learn to refuse.

Her Body and Other Parties features eight stories that manage to be both eerily familiar and also unlike anything you’ve ever read, refurbishing tropes from science fiction, fairy tale, and Law & Order: SVU with formal innovations and psychological insights that make them feel genuinely new. The first story, “The Husband Stitch,” makes they wanted my head disconcertingly literal, revisiting the famous folk tale of the girl with a mysterious ribbon tied alluringly around her neck. As the menacing husband goads the narrator, a master storyteller with a Dickensian gift for performing voices, into untying her green bow, the horror we feel at her decapitation—and resulting silence—resonates throughout as Machado explores the pleasures and perils of the flesh.

Carmen Maria Machado is a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and her work has been published in venues like The New Yorker, Tin House, and Best Women’s Erotica. Her Body and Other Parties is a finalist for this year’s National Book Award in Fiction. She lives in Philadelphia, and spoke to me by phone.

Carmen Maria Machado: A few years ago, I submitted an early draft of “The Resident” to a workshop, a short story that begins with a woman driving up to a writers’ residency in the woods. The comment I got was that the structure reminded people of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, a book I had never read.

This was an experience I’d had before: folks telling me something I’ve written reminds them of a certain writer I’d never read before. It makes sense: It’s the second-hand influence you get when the authors you have read have already internalized the work of someone like Jackson. But when everyone made that comparison, I figured I should probably read this novel.

When I went back home to Philly, I picked up a copy. And I just devoured it. I read it in one sitting. I started reading one night, and when my girlfriend (now wife) went to bed I just kept reading. It scared the shit out of me. Even though the events that appear to be supernatural activity are few and far between, those scenes are so chillingly written—as if Jackson was describing a phenomenon she’d seen before and really understood. The book’s particular brand of surreality felt, to me, like that experience of walking home from a party a little bit drunk, when the world somehow seems sharper and clearer and weirder.

I hadn’t been that genuinely unnerved by a horror novel in a long time. There was just something so instinctive and eerie about the writing, and also the prose was so careful, that it just felt real in this way that was terrifying. I had to go to the bathroom when I finished the book at 3 in the morning but was too scared to get out of bed. Since then, I’ve tried to read everything else Jackson ever wrote: all her short fiction, and most of her novels.

One of my favorite scenes in the book takes place early on, while one of the main characters is on a car trip—the same trip that reminded my workshop of early scenes in “The Resident.” Eleanor has responded to an invitation from a character named Dr. Montague, who is trying to access the supernatural element of Hill House by convening a small group of people with strange, psychic gifts. Eleanor’s this gentle, soft-spoken woman who spent years caring for her ailing mother. But the mother recently died, so she’s living with her domineering sister’s family in this very uncomfortable and unpleasant situation. When she gets Dr. Montague’s invitation, the sister says she can’t borrow the car to go to Hill House—but Eleanor just steals it anyway, which I love. It’s the first gesture this late-blooming character makes to try to take her life back.

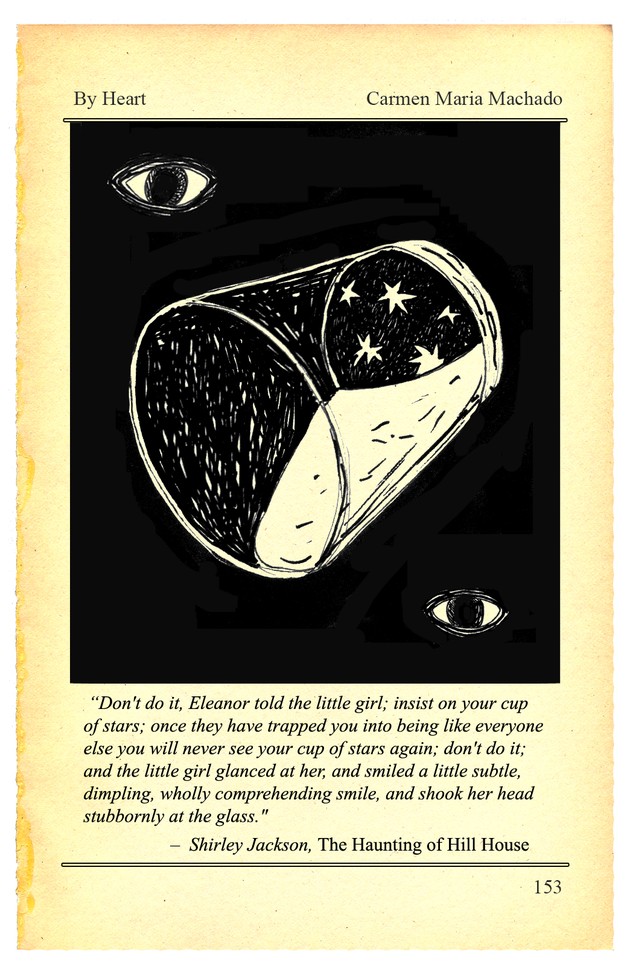

She stops for lunch at this country restaurant, just marveling at how beautiful the scenario is, how good it feels to be on her own. And then she overhears this conversation at a table nearby, where a little girl is refusing to drink her milk. The girl’s mother keeps explaining to the waitress that the girl wants “her cup of stars,” a strange, wonderful detail that at first Jackson allows to remain ambiguous. It turns out that this is the girl’s name for a special cup she has at home, one with stars at the bottom of her glass.

The mother and father are trying to convince the girl to settle for this standard-issue cup.

“You'll have your milk from your cup of stars tonight when we get home,” the mother says. “But just for now, just to be a very good little girl, will you take a little milk from this glass?”

Her parents act as if they would be spoiling the little girl by allowing her to act on these whims. But Eleanor, overhearing all this, silently urges the girl to demand her cup of stars. This wordless command leads to this beautiful moment between them:

Don’t do it, Eleanor told the little girl; insist on your cup of stars; once they have trapped you into being like everyone else you will never see your cup of stars again; don’t do it; and the little girl glanced at her, and smiled a little subtle, dimpling, wholly comprehending smile, and shook her head stubbornly at the glass. Brave girl, Eleanor thought; wise, brave girl.

It’s almost as if Eleanor’s saying: Demand what you want in this world, and don’t let them talk you into anything else. And the girl almost seems to hear her somehow, turning around to give a knowing smile. It’s an incredible moment, and every time I read it I marvel at what a beautiful scene this is.

For me, the cup of stars is a reminder that you are allowed your own fantasies, the particular fancies of your own mind. That everyone deserves this, and should insist upon it. That—even as others tell you the things you want are unrealistic, outrageous, not permitted, or silly—it’s okay to say, I want this.

There absolutely is a gendered element to it—this is an exchange between a woman and a girl, after all. Women are much less allowed their indulgences, in life as well as in fiction. If you think of Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle, I literally cannot comprehend a version of that book written by a woman—not because she couldn’t write it, but because I don’t think she’d be permitted to publish it. I just feel that we, as a society, would not allow a woman to express her rich-enough inner life by writing down every single thing she does and putting it into a book—can you imagine the accusations of self-indulgence? I think that’s where a lot of the energy in Jackson’s work comes from, actually: You sense this dissatisfaction with women’s narratives, the way that women are thought about and portrayed in fiction.

In my work, I think non-realism can be a way to insist on something different. It’s a way to tap into aspects of being a woman that can be surreal or somehow liminal—certain experiences that can feel, even, like horror. It allows you to defamiliarize certain topics like sexual violence that some people might unfortunately dismiss as “oh, just another story about rape.” Non-realism makes room for mythic expressions of the female experience, and I think can be a way to satisfy the hunger for narratives in which women have rich inner lives.

Being queer, too, can feel surreal. There’s this sense that you’re seeing things that other people don't, which I think is true of many groups of people who exist apart from the more culturally dominant perspective. You pick up on currents that other people don’t notice. I remember seeing the new Ghostbusters movie and having a gay revelation about Kate McKinnon’s character—I assure you, that character is queer, even if my straight friends can’t see it. Or the “friendship” between Theodora and Eleanor in The Haunting of Hill House, which is unmistakably some of the gayest shit I’ve ever read, though another reader might miss it entirely. It’s very surreal to have this perspective where you experience reality in a slightly different way, and I think that’s one of the things I’m interested in exploring.

It took about five years to write these stories. A few of them I wrote at Iowa—“Difficult at Parties,” “Real Women Have Bodies,” and “Especially Heinous.” All the others came after. The hardest part was after graduate school, where I didn’t have any funding anymore and I was working retail, which made me cranky and miserable and tired all the time.

I was working at Lush—they make luxury bath and beauty products. I love their products, actually, and still use them, but it was horrible working there. I was unhappy and exhausted, and just felt like I was never going to have time to write again, would never publish anything. At work, I just wanted to be alone, to have the space to think. But people were constantly demanding things from me—of course they were, that’s the job. Sometimes, I could have a moment’s quiet in the back, where cutting soap and weighing it and wrapping it could be this meditative, physical process. But even then, people always seemed to want to fill that space with talking. I just felt like they wanted my head.

What helped, finally, was going to residencies. I work really well when I’m in a space that’s removed from everything and I can focus. I can’t work in snatches—five minutes here, 10 minutes or an hour there. What I need is to be able to tell myself: I have nothing to do today except write, and I’m going to write all day. It was residencies that finally gave me that space.

The world finds ways to weigh on you, to take away that free time, to tell you that you don’t deserve your cup of stars. And I feel that it affects women disproportionately. I’m lucky I don’t have to think about children when I plan my time. I know mothers who really want to go into a residency, but it’s just super hard because they can’t leave their kids. There are some residencies that allow mothers, or have accommodations for children, but most do not. That’s just one example. We don’t allow certain types of people that space for all kinds of reasons; there are so many ways the real world doesn’t value our purest time. When I think about the art that didn’t get created because of stuff like that, it makes me sick and sad.

I am driven to find that. Even if it’s just my own mind, I want to have my cup of stars. The response to that attitude can be: Oh, that’s so selfish. Or: That’s so not accommodating to other people’s needs. Or: How dare you demand that thing? But you have to. “I want it,” we deserve to say. “Give it to me.”