What Would Miss Rumphius Do?

Barbara Cooney’s beloved stories and illustrations carry lessons for young Americans about moral courage.

Nineteen fifty-nine was a year of soft amusements for children. Dr. Seuss’s zany Happy Birthday to You! arrived in bookstores and Mattel introduced Americans to the Barbie doll and her frozen plastic gaze. On TV, suburban comedies like Father Knows Best and Dennis the Menace administered doses of mild humor laced with bland moral guidance.

But the Caldecott Medal, the premier American award for picture books, registered a note of dissent. It recognized Chanticleer and the Fox, the first picture book written by a young illustrator named Barbara Cooney. Adapted from the salty Middle English of The Canterbury Tales, the book tells the story of a proud rooster, Chanticleer, who falls prey to a fox’s flattery. Just as the fox is about to devour him, the rooster turns the tables, tricks the fox into opening his mouth, and escapes. The book ends with the rooster and the fox conversing, each ruing his own foolishness and impulsiveness.

In her acceptance speech for the award, the small blond author, gesturing with her long hands, conceded the anomaly of her book. “Much of what I put into my pictures,” she admitted, “will not be understood.” But she had chosen to write it because she thought that the “children in this country need a more robust literary diet than they are getting.” “It does not hurt them,” Cooney insisted before her audience of senior librarians and educators, to hear about the real stuff of life, about “good and evil, love and hate, life and death.” (She did not say so that evening, but she had already experienced a good bit of each.) She vowed that she would never “talk down to—or draw down to—children.”

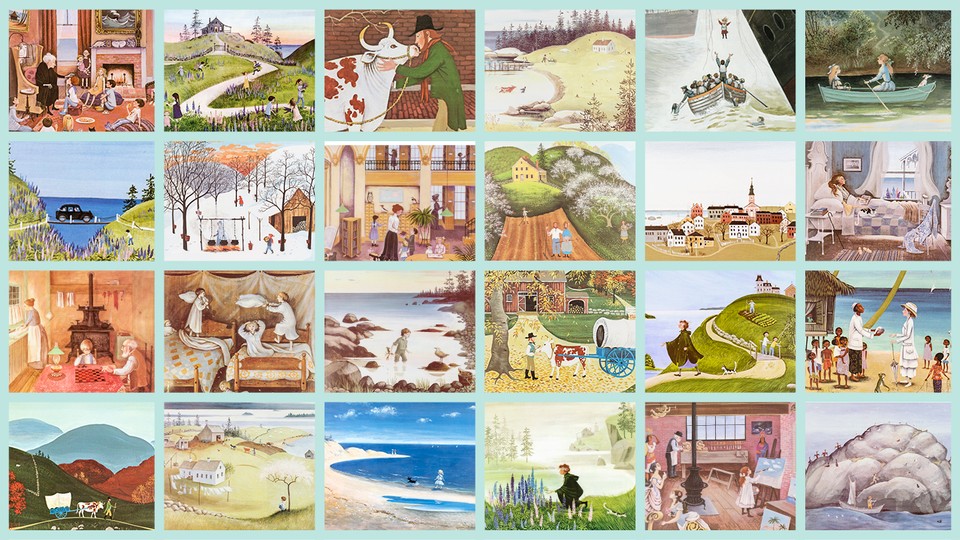

Children’s books are more than just entertainment. They reflect how a society sees its young and itself. By shaping the attitudes and aspirations of children, they help shape the world those children will grow up to inherit. Barbara Cooney went on to have a long and celebrated career in American picture books. She illustrated or wrote some 100, including modern classics such as Miss Rumphius and Ox-Cart Man (which garnered her another Caldecott Medal, in 1980). Her books are still beloved, nearly two decades after her death, by readers who admire their visual charm and rich historical storytelling. But Cooney’s greatest gifts, manifest in her work from the start, are more profound. Her singular vision of young Americans and her unique ideas about how to write for them make her books more relevant to Americans today—and perhaps more necessary—than ever before.

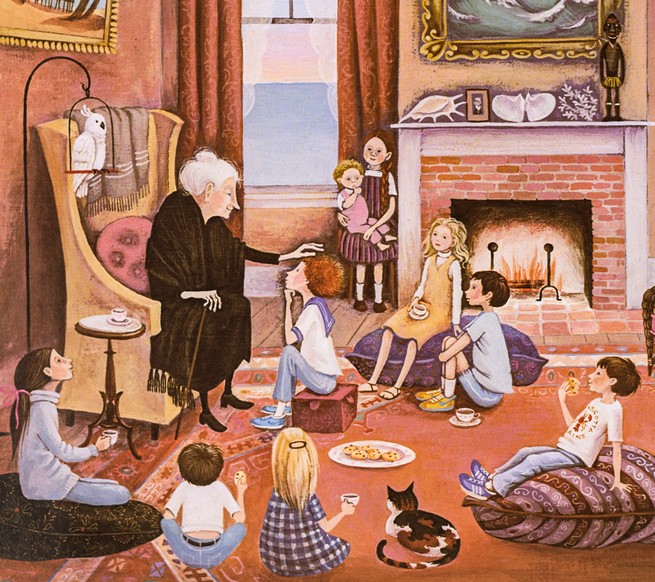

I first discovered Cooney when a friend gave my 3-year-old daughter a copy of Miss Rumphius (1982). As happens with some children and some books, Suzanne demanded to hear it over and over. The deceptively simple story follows Alice Rumphius through the arc of her life. The book begins with the young girl listening to her immigrant grandfather’s “stories of faraway places.” She declares that she, too, will travel and then return to live in a home by the sea. Her grandfather likes her idea, but adds that she must also “make the world more beautiful.” “All right,” Alice says, and for the rest of the book she strives toward her three goals. On the next-to-last page, we see the circle of her life completed as Alice’s niece—also named Alice—has the same conversation with her now-aged namesake in her home by the sea.

As the readings multiplied, instead of becoming tired of the book I found myself more and more immersed. There is much to like in Miss Rumphius. Cooney’s pictures, in rich colors with a spare, faux-naïf flatness that evokes American folk painting, are filled with fine details that catch the eye. Alice’s journey to “make the world more beautiful” is touching. The cyclical, generational architecture of the story, in which the young girl of the first pages is an old woman by the end, is very satisfying.

Still, the story pulled at something more in me, something deeper. Cooney draws the portrait of a rare kind of person: someone with an inner compass who allows herself to be guided by it even when the course it charts is not so easy. Miss Rumphius never marries and has no family of her own. (Cooney leaves unstated that this decision would have made her highly unusual in the book’s early-20th-century setting.) Alice encounters obstacles and setbacks on her path, as we all do, but she remains absolutely steady, absorbing the judgments of others and her physical failings with equanimity. Without the slightest hint of preaching, Cooney models for her young readers how they can live an intentional life, one in which they imagine a future for themselves and go toward it without fear.

What impressed me most about this portrait was Cooney’s refusal to sugarcoat it. Following her own course, Alice lives a solitary life. Cooney explores with unsparing frankness the loneliness enlaced with her protagonist’s self-possession. Though Alice makes “friends she would never forget” everywhere along her journey, Cooney dwells visually on her moments of solitude. There she stands alone beside her house by the sea; there she goes, accompanied only by a cat, scattering lupine seeds to make the world more beautiful. After she starts her sowing, the people of her town dismiss her as “That Crazy Old Lady.” Don’t think it’s easy, Cooney seems to whisper to her readers, to live such a self-directed life.

Barbara Cooney knew what it meant to be lonely. She was born 100 years ago, in 1917 in Brooklyn, to a prosperous German Irish family. Both sides of her family had risen from immigrant roots to wealth and social prominence by the turn of the 20th century. Cooney’s father went to Yale, her mother attended the elite Packer Collegiate Institute in Brooklyn, and Cooney herself matriculated at Smith College.

Cooney was the odd one out in her family. Her father, Russell, playing the conservative patriarch, favored her three male siblings. The slight, unconventional girl found her greatest happiness during summers at the family’s compound in Waldoboro, Maine. The little New England town settled by Germans in the 18th century had a comfortable feeling for Cooney and her mother.

After finishing college, in 1938, she returned to New York hoping to write for children. She had little formal artistic training, and her career got off to a spluttering start. The small but prestigious publisher Farrar & Rinehart issued three charming chapter books, all set on the Maine coast, which she wrote and illustrated in plain black and white. None of them had great success.

Soon after her first book appeared, Cooney met and quickly married Guy Murchie, a tall and worldly writer, and a son of one of Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. Within the space of three years they had two children, whom Cooney named Gretel and Barnaby, after characters in classic fables. But the marriage did not last. Cooney discovered that Murchie was a “cad” and a “womanizer,” as her children later put it. Having suffered through several painful years, she decided to move out.

At a time when divorced single parenthood was exceedingly rare, striking out on her own cannot have been simple. Cooney’s father and twin brother had disapproved of her marriage and disowned her. She supported her family by setting aside her own writing and turning full-time to illustration. She took on seemingly every project she was offered, including a collection of folk songs for children and several progressive educational tracts, with titles like Teacher Listen, the Children Speak. She integrated her small family into her work, setting up an antique drafting table in the living room and using her children as models.

In 1949, Cooney remarried and settled in Pepperell, Massachusetts. She and her new husband, the town physician, Charles Talbot Porter, had two more children. In spite of their newfound stability, though, Cooney and her family stood out. In a town where almost no women of her class had a career, she regularly put in six-hour days at her desk, illustrating as many as half a dozen books a year. Just as unusual, Cooney interacted with her children as though they were not simply her charges but her friends. She eagerly encouraged their creative impulses. They built canoes, tried to mine for coal in the yard, and put on a circus complete with a lion tamer and a high-wire act. And every night, the whole family came together for long discussions over a late, candlelit dinner.

Barnaby, the main character of The Little Juggler (1961), the second picture book Cooney wrote, might have been at home in the Porter household of the 1950s. He is an orphaned tumbler living in medieval France. In Cooney’s version of the often retold French legend, the penniless boy is chagrined that he has no Christmas gift to offer the Virgin Mary. Even without possessions, though, he realizes that he still has his tricks. On Christmas Eve, he sneaks into a chapel and performs before a statue of the Virgin until he collapses. Two monks are scandalized by what they take to be his levity. But when the Virgin appears and revives the little tumbler, they realize their error and allow him to stay with them.

Cooney’s Barnaby is unlike the Barnaby that one finds in most other versions of the tale. In her hands, the story is not about the naive wisdom of a child or a simpleton. Cooney reimagines Barnaby as the equal of any adult. He suffers real penury and makes deliberate decisions that lead to his offering in dance. The Virgin’s rebuke of the monks and her embrace of the child serve as supernatural confirmation of the child’s natural parity with his elders.

Barnaby, wittingly or not, is part of a very old argument about the nature of children, which Americans have been having both in and out of books since long before there was a United States. Are children basically like adults, or are they essentially different from us? In premodern times, the French scholar Philippe Ariès famously argued, there was no childhood in the sense that we understand it. Children were imagined as little adults, just the way that they were depicted in many paintings. Books for them were made to match. When New England children studied the alphabet in The New England Primer, for instance, they learned that they had to choose whether they would be sinners or saints, whether they wanted to live or die.

In the early 19th century, a “Romantic vision of childhood” (as the historian Steven Mintz calls it) supplanted these earlier ideas. Middle-class Victorians reconceived of childhood as an idyll, free from worry and fears of all kinds. They thought that it had to be so, because they imagined their children as fragile and incapable beings. To enjoy this period of life, children had to be shielded from the discomfiting realities of grown-up existence. It is no surprise that Victorian books for children skewed toward sanitized fairy tales, tame fantasies, and anachronistic histories. More than a century later, these notions continue to echo in the vast number of children’s books that paint a rosy, untroubled picture of the world, as though that were all young minds were able to bear.

For Cooney, the Victorian vision of children made no sense. Influenced by her experiences as a child and as a parent, she thought that children were moral and intellectual agents—and should be taught to see themselves as such. (Her encounters with progressive education may have also encouraged this belief.) Like Alice Rumphius, Barnaby the tumbler has a kind of moral seriousness and resourcefulness about him, which makes him more reminiscent of the hardy offspring of Puritans than the innocent babes of Victorian fantasy.

The moral gravity of her child characters lends Cooney’s stories an old-fashioned air. But the view of children’s capacities that she embraced has come to seem rather prescient. Experiments in child psychology over the past 30 years have revealed that children are far more morally and intellectually sophisticated than many people once believed. Toddlers engage in inductive reasoning. From a very young age, children can distinguish right from wrong. Indeed, in some ways, children draw more readily on their abilities than we do on ours. They are quicker than adults, for instance, to learn and generalize from their experiences. Cooney didn’t know about this research. But she came to similar conclusions on her own and wove her respect for children’s minds into all her books.

The success of Chanticleer and the Fox gave Cooney a wider berth than she had had before to pursue her vision. She had always been deeply interested in folktales and fables from around the world. Publishers now associated her with that genre and offered her a regular stream of them to illustrate. During the 1960s and early ’70s, she made pictures for more than a dozen books based on folktales. As she had with Chanticleer, she aimed to meticulously reconstruct each story’s historical setting. She began to do research abroad. Cooney traveled extensively over several decades, including to France, Spain, Greece, North Africa, Mexico, and Oceania. She returned from each trip with notebooks full of interlaced text and images, as well as hundreds of photographs and boxes of reference books.

The ’60s engrossed Cooney. She had never been overtly political, and she remained more of an observer than an active participant. What really interested her about politics was its human drama: how it revealed the “struggles” of individuals, as her daughter-in-law put it, to make their way in life. There was now a great deal of such drama to watch, even in Pepperell. Cooney eagerly followed the progress of the civil-rights movement, supported John F. Kennedy and George McGovern, and swam along with the feminist movement. She read Simone de Beauvoir, perhaps in the original French, and became more vocal about her long-held belief in women’s rights.

Cooney started experimenting with new visual forms. Until the early ’60s, she had worked largely in scratchboard (a technique that involves using a stylus on a specially prepared board). Now freed from the obligation to work in cheap-to-print media, she began using colored pencils and acrylic and oil paints. Even as she shifted to different ways of illustrating, though, she retained the flatness and sharp contours that had become a hallmark of her pictures during the decades of work in scratchboard.

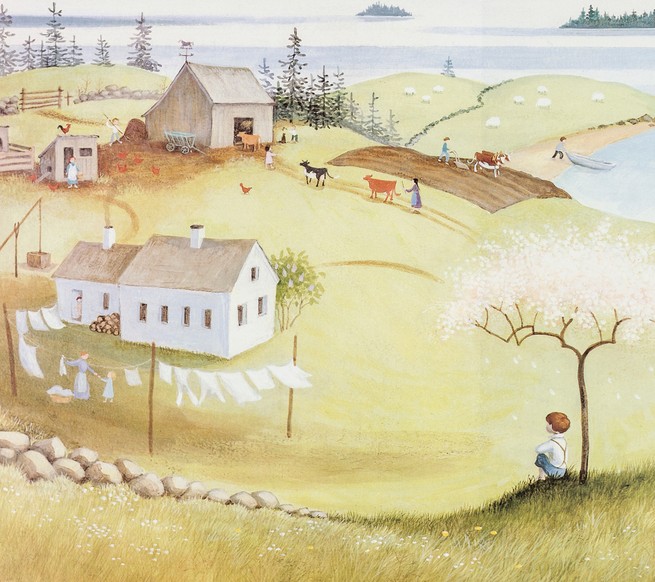

Her new style had fully matured by the time she illustrated Ox-Cart Man, the 1979 book that won Cooney a second Caldecott Medal. The rhythmic, nearly hypnotic text by the poet Donald Hall depicts the cycle of a premodern New England family’s life. It starts with the family loading a cart in the fall with goods to take to market. By the end, we are in late spring, watching the family accumulate the exact same set of goods for another year. This is a book in which, by a certain measure, nothing really happens at all.

Cooney’s pictures, though period-appropriate to a tee, transform the story into a meditation on love and loss. At the center of the book, she devotes a full page to a single line of Hall’s text: The farmer “sold his ox, and kissed him good-bye on his nose.” Cooney shows the farmer, his hands gently embracing the ox’s head and his face serious, about to put his lips to his companion’s pink muzzle. The only other presences in the picture are a skeletal tree and a carpet of fallen leaves. Half a dozen pages later, though, the sprightly tail and hindquarters of an ox calf in the barn assure us that the cycle is recommencing.

Like Miss Rumphius, which appeared in print three years later, Ox-Cart Man is about change and stability, the two poles of a small child’s life (and of any life). The genius of both of these books is how they use the stability of cycles to steady the destabilizing reality of change. A cycle, whether of seasons or generations, is after all just a form of change that promises continuity and return. The loneliness of Alice Rumphius and the passing of the years on the farm are subsumed, each in turn, by the reassuring thrum of the larger rhythms of life.

Miss Rumphius and Ox-Cart Man both appeared as the conservative movement’s triumph brought a close to liberalism’s long postwar reign. Ronald Reagan and the movement’s other storytellers fueled their assault on the liberal consensus with a vivid and nostalgic retelling of the national past, celebrating cultural homogeneity, hierarchy, and an up-by-the-bootstraps ethos of success. It is surely no coincidence that just as this narrative spread, Cooney, an avowed liberal, began for the first time in her long career to create her own American myth. In a string of books that are among her finest, including three that she wrote and illustrated—Island Boy (1988), Hattie and the Wild Waves (1990), and Eleanor (1996)—she sketched an alternative vision of the American past.

Cooney’s books from these years set one of her habitual outsider figures—immigrants, loners, people guided by an inner light—at the center of an unmistakably American story. Island Boy, which echoes Miss Rumphius at several points, tells the story of Matthais Tibbetts, a boy living off the Maine coast in the 19th century. Hattie is a lightly fictionalized biography of Cooney’s mother and her upbringing in turn-of-the-century immigrant Brooklyn. Eleanor is the story of Eleanor Roosevelt’s childhood. Each protagonist’s life offers a counterpoint to the Reaganite fantasy: an American history built on moral precocity, empathy, and an abiding concern for others.

Matthais and Hattie share the self-awareness of Alice Rumphius. Like her, both declare their intentions for the future at a young age. Little Matthais longs to be useful around the farm, in spite of his older brothers’ scornful dismissal. Hattie announces to her skeptical family her plan to become a painter. They share Alice’s occasional lonesomeness, too. On the second page of Island Boy, baby Matthais is already alone, sleeping apart from his many brothers and sisters. And when his brothers give him the brush-off, he goes to sit by himself “under the red astrakhan apple tree” beneath which, many pages later, he will be buried. An “island boy” indeed.

The child protagonists of these three books have an extraordinary empathy for other outcasts and strangers. Eleanor always thinks about “people less fortunate—about the newsboys and the people of Hell’s Kitchen.” The boy Matthais, in perhaps the most affecting passage of a moving book, adopts a baby seagull he finds orphaned on the “Egg Rock.” He cares for it, feeding it seafood and “pie and doughnuts,” and the little bird follows him everywhere. Eventually he teaches it to fly and sends it “home.” Matthais’s empathy helps make him into something of a feminist avant la lettre. When he and his wife, Hannah, return to the island and have three girls, his brothers again scoff—“A farmer needs sons for the heavy work”—but Matthais ignores them. “Women and girls can work mighty hard too,” says Hannah, and her husband seems to agree.

In Eleanor, completed just a few years before her death in 2000, Cooney made her most insistent statement about the attributes that make a great American. The book took shape while Cooney was working on a never-completed project that was to be the story of a male artist’s childhood. Like most of Cooney’s protagonists, Eleanor is lonely. Unlike most of them, she has her isolation thrust on her by others. “From the beginning,” the book opens with a punch, “the baby was a disappointment to her mother.” (Who but Cooney would dare begin a book for children with such dark words?) Things immediately go from bad to worse. Little Eleanor is spurned by much of her family and orphaned at the age of 9. But though she is shy and awkward, she shows glints of that steely Cooney steadiness; she always tries to be brave.

Eleanor’s luck finally starts to turn when she goes away at 15 to boarding school in England. With the help of the school’s headmistress, the “sad young girl” soon finds her footing. She discovers her strengths, learns to “think for herself,” and in short order becomes a mentor to other “lonely girls.” She returns home to America “poised and confident, brave, loyal, and true.” The book’s epilogue, which telegraphically recaps her later life, concludes with Adlai Stevenson’s eulogy to the United Nations General Assembly: “She would rather light candles than curse the darkness.” The line never fails to leave me with tears starting in my eyes.

Like so much of Cooney’s work, these late books have an oddly timely quality. What it means to be an American is in question now as much as it was several decades ago, when they first appeared in print. The civic virtues that they model are no less under threat. To read Island Boy or Eleanor, or even Miss Rumphius, today is to encounter a vision of America as a nation shaped by those who are on the outside, the oddballs and the introverts. These are the people, Cooney suggests, who know themselves and their minds and who have the steady self-knowledge to build a society. These books, these characters, offer an idealized reflection of an America that could be, a country whose culture values empathy and patience—two qualities that seem now to be in short supply.

Children born today will face no small amount of uncertainty as the future unfolds. Cooney’s characters, by exhibiting the virtues of foresight and moral courage, might be able to help. I can well imagine a child today sitting on a grandparent’s knee, just as Alice Rumphius did, and declaring an intention to make the world better. Cooney would certainly have wanted that. For her, as she said in her 1980 Caldecott Medal acceptance speech, the point was not to make “picture books for children.” The point was to make them “for people.”

My daughter, I have to admit, is getting a bit too old for Barbara Cooney’s books. The excitement Suzanne used to feel in hearing them over and over has dimmed. When she sees them on my desk now, she jokes that they are my books. I feel a little sad about that. But in a funny way, Cooney predicted that this would happen and so robbed the moment of its sting. Life and time, in her world, always move in circles. And so in Suzanne’s loss of interest, I can already begin to see the turning of the wheel: the first increment in the long rotation by which she will go from the child, listening with rapt attention, to the adult who will read them to a daughter or son of her own.

*Opening illustration credits: Ox-Cart Man (1979), Miss Rumphius (1982), Island Boy (1988), Hattie and the Wild Waves (1990), Eleanor (1996). Illustrations © Barbara Cooney Porter. Used with the permission of Viking Children’s Books.