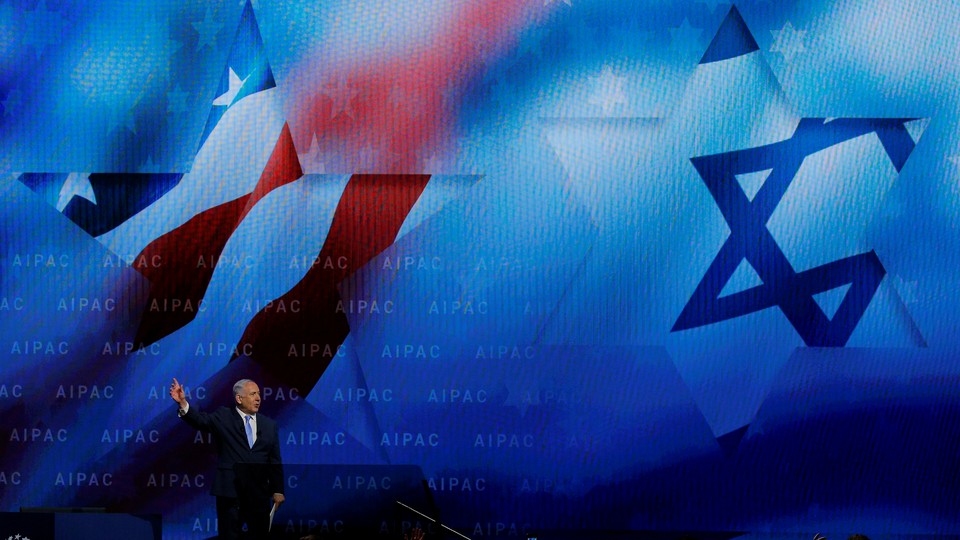

AIPAC's Struggle to Avoid the Fate of the NRA

The organization is desperately trying to maintain its bipartisan membership and avoid the pull of polarization—but it’s almost certain to fail.

Commentators sometimes compare the American Israel Public Affairs Committee to the National Rifle Association. Both are powerful, controversial, single-issue, lobbying organizations. And both have had enormous success in shaping the Washington agenda.

But in their DNA, the two groups are utterly different. The NRA thrives on culture war. It produces videos attacking “lying member[s] of the media,” “Hollywood phon[ies],” and “athletes who use their free speech to alter and undermine what our flag represents.” Last week, at the annual Conservative Political Action Conference, NRA head Wayne LaPierre warned of “socialists” who seek “to deny citizens their basic freedoms.”

Many of the progressives who loathe the NRA loathe AIPAC, too. But you’ll never find AIPAC’s leaders at a CPAC conference. That’s because while the NRA feeds off of ideological and partisan polarization, AIPAC fears it. While the NRA can maintain its influence via hardcore partisanship, AIPAC can only succeed by working with whoever is in power.

AIPAC fears polarization because its mission requires wielding influence inside both parties. The NRA doesn’t need to work with Democratic presidents. It needs merely to mobilize its largely Republican congressional allies to block any gun-control measures a Democratic president might push. AIPAC, by contrast, is constantly massaging the relationship between Washington and Jerusalem. That requires good relations with the members of Congress chairing the Foreign Affairs and Armed Services committees. It requires constant contact with the Pentagon over U.S. arms sales and military exchanges, with the State Department and National Security Council over diplomatic initiatives, and with the Treasury Department over sanctions against common adversaries like Iran.

Unlike the NRA, AIPAC must do business with whoever runs Congress and the White House, policy disagreements notwithstanding. Thus, when President Obama in 2011 invited the NRA to the White House to discuss gun safety, LaPierre responded: “Why should I or the NRA go sit down with a group of people that have spent a lifetime trying to destroy the Second Amendment?” But that December, AIPAC CEO Howard Kohr attended the White House Hanukkah party.

But AIPAC doesn’t only fear polarization because it could undermine its influence. It also fears polarization because it could split the organization in two. Unlike the NRA, which according to a 2017 Pew Research Center poll boasts a membership that is more than three-quarters Republican, AIPAC’s members are likely split fairly evenly between the two parties. When Vice President Mike Pence praised Trump on Monday night, around half of the AIPAC attendees stood up to applaud.

AIPAC’s problem is that its bipartisanship is becoming harder to maintain. Democrats may constitute roughly half of AIPAC’s members, but their share could plummet in the years to come. The reason is simple. Many older American Jews see Israel through a different lens than other issues. Their broader liberalism inclines them to vote Democratic. But their anxiety about Jewish safety and commitment to the Zionist project incline them to join AIPAC.

AIPAC’s problem is that younger American Jews are less likely to bifurcate their views in this way. They are less likely to have personally experienced anti-Semitism. They are less likely to know relatives who survived the Holocaust. And they are less likely to have witnessed events like the 1967 and 1973 wars, when Israel’s existence appeared to be in peril. To the contrary, they have come of age seeing both American Jews, and the Jewish state, as privileged and powerful.

Thus, they are more likely to inherit their parents’ progressivism than their parents’ Zionism. The same concern for human rights and equality that informs their general political outlook makes them unsympathetic to Israel’s policy of holding millions of Palestinians under military occupation, without basic rights, in the West Bank. Which puts them at odds with AIPAC. They are also generally more assimilated than their parents, which means that—irrespective of their politics—they care about Israel less. Which means they’re less likely to join AIPAC.

It’s not that AIPAC doesn’t attract young people. It does. But those young people are disproportionately Orthodox. Orthodox Jews are rising as a share of the American Jewish population. And younger modern Orthodox Jews—many of whom attend intensely Zionist yeshiva day schools and spend a year studying in Israel between high school and college—generally feel a stronger connection to Israel than their non-Orthodox counterparts.

For AIPAC, this rising cohort of young Orthodox Jews is both a blessing and a curse. It’s a blessing because it means AIPAC can sustain itself at a time when assimilation is weakening many other Jewish institutions. But it’s a curse because it undermines AIPAC’s bipartisanship. Orthodox Jewry has become overwhelmingly Republican. Last September, an American Jewish Committee poll found that 71 percent of Orthodox Jews approved of Trump.

Younger Orthodox Jews aren’t bifurcating either. The same emphasis on security, nationalism, and traditional religious morality—the same tendency to see the world in zero-sum, us-versus-them terms—that makes them hawkish on Israel makes them comfortable inside the GOP. You can see the ideological effects of this growing Orthodox influence in the smaller Zionist Organization of America, which has hosted Steve Bannon, endorsed Trump’s travel ban, and fought to keep Black Lives Matter out of public schools. And you saw it in Ted Cruz’s presidential campaign, which developed an entire Orthodox fundraising strategy. Were AIPAC to surf these demographic and ideological trends, it would become heavily Orthodox, overwhelmingly Republican, and more and more openly hostile to the American left—a pro-Israel version of the NRA.

If this year’s AIPAC conference had a theme, it was a loud, almost desperate, vow by the organization’s leaders to not let this happen. On Sunday morning, the group’s lay president, Mort Fridman, explicitly addressed “my friends in the progressive community.” He insisted that, “The progressive narrative for Israel is just as compelling and critical as the conservative one. There are very real forces trying to pull you out of this hall and out of this movement and we cannot let that happen—we will not let that happen!” That evening, Kohr explicitly endorsed “two states for two peoples”—thus putting AIPAC, at least rhetorically, to Benjamin Netanyahu’s left. In between their talks, AIPAC featured former Michigan Governor Jennifer Granholm, who called Israel a “progressive paradise.” The evening ended with a performance by the Howard University Gospel Choir.

AIPAC is conducting a remarkable experiment. It’s doubling down on bipartisanship and ideological diversity even as tectonic shifts in American politics and culture make that harder and harder. It’s doing so even though it could alienate its rising base on the right, who might defect to groups like the ZOA. Indeed, the ZOA slammed Kohr’s endorsement of the two-state solution, as did Breitbart.

It’s fascinating to watch, and it’s likely to fail. It won’t fail because younger liberals can’t find things to admire in Israel. They can. It will fail because the thing about Israel that young liberals admire least is its half-century long policy of denying Palestinians in the West Bank basic rights like free movement, due process, and citizenship in the country in which they live—and entrenching that denial by building settlements where Jews enjoy rights that their Palestinian neighbors are denied. Kohr’s endorsement of the two-state solution notwithstanding, AIPAC remains the most powerful force in American politics opposing pressure on Israel to end the occupation. Thus, young liberals can only embrace AIPAC if they place their support for Israel ahead of their opposition to its occupation.

That’s not likely to happen. To the contrary, young American Jewish liberals are more aware of—and more disturbed by—the occupation than their elders. That’s partly because young, non-Orthodox, American Jews are less likely to excuse Israeli behavior in the name of Jewish survival. And it’s partly because the United States contains a growing population of American-born Palestinians, Arabs, and Muslims who speak fluently the language of the American left. These young Palestinian, Arab, and Muslim Americans find it easy to frame their criticisms of Israel in terms that other people of color find compelling. Thus, on college campus after college campus, progressive activists unite in fierce opposition to Israel’s policies, if not its very existence. Progressive Jewish students respond by either embracing that critique, ignoring it, or combatting it, which tends to push them into the arms of the right.

The Millennial campus activists of today are the Democratic Party activists of tomorrow. Already, they are pushing the party leftward. Polling suggests it’s happening on Israel too.

AIPAC understands these trends well. And it’s desperate to counter them, to find a message that keeps progressives in the tent. But, at the end of the day, most young liberal American Jews don’t think AIPAC has a message problem. They think it has a moral problem. AIPAC, in their view, is asking progressives to support Israel’s right to deny to one religious-ethnic group the rights it guarantees to another. Which means that AIPAC, as they see it, is asking progressives to not really be progressive at all.