How the Dutch Do Sex Ed

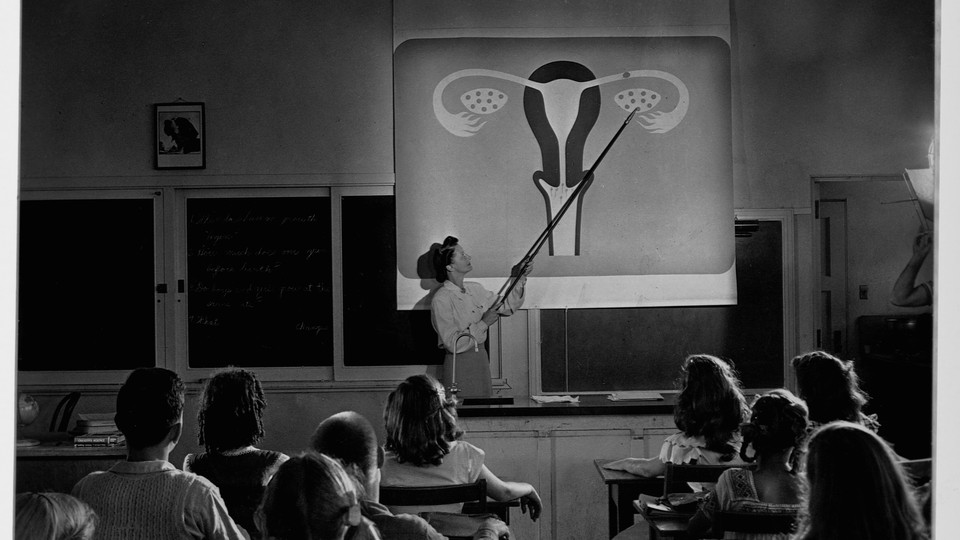

In the Netherlands, one of the world’s most gender-equal countries, kids learn about sex and bodies starting at age 4.

Stepping into Nemo, Amsterdam’s science museum, visitors encounter the usual displays: bubbling vinegar, kinetic games, chain reactions, hydropower demonstrations, and experiments with lenses, prisms, and mirrors. But upstairs in the Teen Facts gallery, an area dedicated solely to puberty and sex, unsuspecting parents might be forced into a quick decision: proceed with the kids, or hightail it to another exhibit?

As an American parent visiting Nemo over the years, I’ve noticed that Dutch families hardly blink at the permanent Teen Facts display. There, guests of any age can put their arms in tongue puppets to mimic French kissing. They can learn about hormones, mood swings, and zits. Guests can peer into a tank of white ooze representing a lifetime’s manufacture of semen, then settle in to watch a giant cartoon, on loop, in which a boy and a girl traverse puberty side by side.

Behind a velvet curtain for patrons ages 12 and older, there’s more: a video about orgasms (faces only), a display of novelty condoms and old-fashioned birth-control methods, and a shelf of wooden mannequins glued together in zoo-like acts from the Kama Sutra. On the wall, a guide to good sex printed in Dutch and English encourages plenty of educational “solo sex” and honest partner communication: “Tell or guide your partner around your body. Don’t worry about losing control ... Your pleasure is your partner’s delight.”

Over the past 30 years, more and more American sex-ed classrooms have shifted toward abstinence-only messages and away from more effective curriculums. Yet, over that same time period, Dutch sex education—in classrooms, but also in public spaces like Nemo—has gotten progressively more comprehensive, and the Netherlands now outperforms most countries on various global metrics for sexual-health outcomes. On average, Dutch and American teenagers have sex for the first time around the same age—between 17 and 18—but with dramatically different results. Teen pregnancy has been on the decline in the U.S. for the past three decades, but American teenagers still give birth at five times the rate of their Dutch peers, who also have fewer abortions. In the United States, people under 25 make up half of all new STI cases each year, while young people in the Netherlands account for 10 percent of new cases in the country. Socially, sex is different, too: Sexually active young people in Holland sleep around less, communicate more often with their partners about their likes and dislikes, and report higher rates of sexual satisfaction.

While researching my new book on sex education, I observed how Dutch parents, health-care workers, and educators achieve these public-health results by being almost unbelievably open with children of all ages about bodies and relationships. And, in part because of its low teen-birth rate, the Netherlands ranks as one of the most gender-equal countries in the world, placing third on the United Nations Development Program Gender Inequality Index. The U.S., meanwhile, doesn’t even crack the top 40.

Research shows that starting sex ed early can help prevent unwanted pregnancies and even sexual abuse later down the road. For the U.S., where talking about human sexuality, particularly with kids, is still in many ways taboo, the Netherlands provides a useful reminder of how robust sex education, and a comfort with seeing and speaking about sex and bodies, can pay major dividends.

In the Netherlands, younger children commonly play naked outdoors and in public wading pools. In doctors’ offices, Dutch parents can access health guidelines encouraging them to support babies and children who want to explore their own bodies. While today’s recommended script for an American adult catching a kid with a hand in their pants is “it’s okay in private,” it’s accepted in the Netherlands that privacy isn’t always practical in the early stages of physical self-discovery (or even a concept kids understand). Many Dutch parents and even teachers permit children to play “doctor” or other show-me games together, as long as children follow set rules: mutual agreement, no hurting, and respect for boundaries. In contrast, American experts usually say such play should be stopped. As kids get older and teen romance blooms, instead of forbidding sex, it’s common for Dutch parents to keep open lines of communication with their children, supporting them in decision making and preparedness.

Since 2012, the Dutch education minister has mandated that all students, beginning in primary school, receive some form of sexuality education that includes lessons on health, tolerance, and assertiveness. The core objectives are to prevent sexual coercion, crossed boundaries, and homophobic behavior, as well as to promote inclusion. And new research confirms that students who receive comprehensive sexuality education in school—that is, lessons on sexual diversity and inclusiveness in addition to biological lessons—are less likely to engage in name calling and more willing to intervene when a LGBTQ or female peer is bullied in school.

In Dutch schools that use the country’s most popular sex-ed curriculum, Kriebels in je buik (Butterflies in Your Stomach), yearly lessons begin with 4-, 5-, and 6-year-olds talking about differences between male and female bodies, learning about reproduction, and discovering their own sexual likes, dislikes, and boundaries. Third-graders learn about love, including how to be kind to your crush. Before middle school, children get lessons on sexual diversity, gender identity, deciding when to have sex, and how to use barriers and contraceptives. All along, students are schooled in healthy relationships and how to reject gender-role stereotypes. (Gender-stereotypical thinking is a risk factor for poor sexual-health outcomes.)

In contrast to the nationwide blanket approach to school sex ed in the Netherlands, fewer than half of American high schools and only 20 percent of middle schools—let alone elementary schools—provide instruction on all 16 topics that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevents (CDC) considers critical to sexual-health education. Schools mostly operate under state and local, not federal, control, meaning that the quality of American sex ed differs enormously from state to state and district to district.

Of course, no country is immune to sexual violence, but sex ed serves as an important bulwark against it. As the CDC reported in 2016, “comprehensive sex education programs have been shown to reduce high risk sexual behavior, a clear factor for sexual violence victimization and perpetration.” In the Netherlands, Kriebels in je buik and other sex-education curricula attempt to instill known preventative factors such as empathy and concern for how one’s actions affect others.

While health matters such as birth control and abortion access are considered private rather than public concerns in the Netherlands and other more gender-equal countries, in the U.S., partisan politics can whiplash policies and programs geared toward sexual health. For example, the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program, initiated in President Obama’s first term and credited with a massive reduction in teenage pregnancy, has been transformed by the Trump administration to favor abstinence-only education, despite a mountain of evidence showing that abstinence programs are ineffective at preventing sexual activity and can leave young people uninformed and unprepared when they do have sex.

Americans overwhelmingly favor medically accurate sex ed in schools, and calls to action in the #MeToo era have parents and teachers wondering how to bring new, more egalitarian ideas about sex and gender to the next generation. The answer may rest in emulating those who normalize human sexuality by getting the facts of life out in the open early and often—at home, in school, or even at the science museum. Given how politicized sex education is in the U.S., it may be easier for families to impart these lessons at home than to change curriculums at a national level. But teaching young children that human anatomy and reproduction are normal—even mundane—makes way for the most essential lessons about our bodies: how to care for, respect, and enjoy them.