The Silent Victims of the Media Baron

From the doctor’s office to the pop charts, the CBS chief Les Moonves’s desires and grudges reportedly took a variety of less obvious tolls.

Sex or power. Biology or culture. Inevitable or changeable. These are the dichotomies embedded in the debate around the #MeToo movement. On one side are those who tend to say that power is the issue: Harvey Weinstein abused his status in ways that lay bare larger structural inequalities that should be rectified. Others ask whether the problem isn’t just that Weinstein was a special kind of creep whose alleged crimes do not, perhaps, require a comprehensive referendum on gender and other cultural hierarchies.

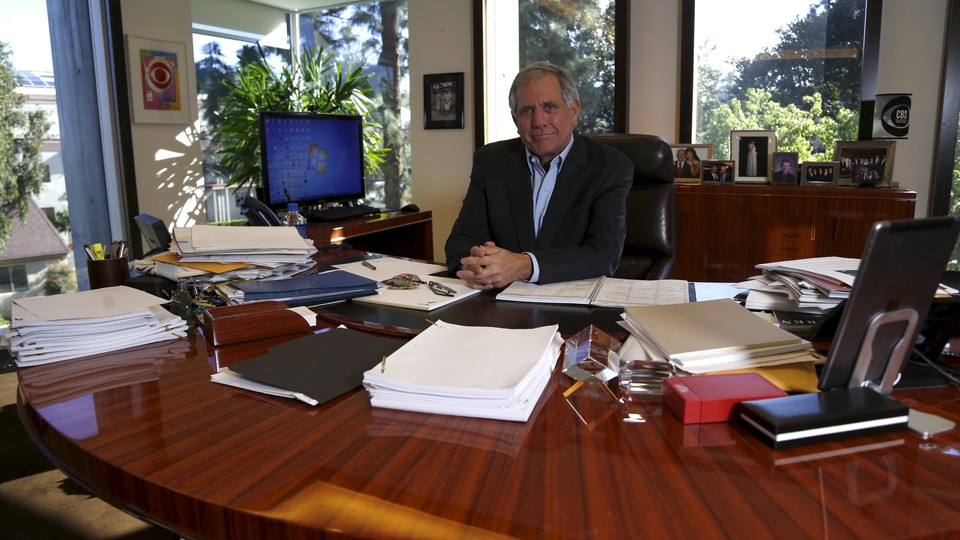

In the basket of allegations against the latest and arguably most significant media man to fall, the CBS chief Leslie Moonves, is intelligence that further clarifies the debate. At least 12 women have accused the now-outgoing TV executive of unwanted touching and vindictive reprisals. Certain specifics create a portrait of Moonves that colors even his conduct unrelated to alleged sexual harassment. What unifies the stories is not only how Moonves acted, though. It’s also the effect those actions had.

The New Yorker has broken most of the allegations against Moonves—which have largely been leveled by people in the film and TV industries—but one telling story arrives from elsewhere. “A Physician’s Place in the #MeToo Movement” read the headline on an Annals of Internal Medicine article published last May by Anne L. Peters, who recounted an anecdote about a “VIP” patient grabbing and trying to kiss her, and then masturbating in front of her when she rebuffed him. The article didn’t identify the patient, but Vanity Fair’s William D. Cohan was told by a source that it was Moonves, who did visit Peters one time in 1999. In a statement issued through a representative, Moonves then appeared to confirm parts of the story: “The appalling allegations about my conduct toward a female physician some 20 years ago are untrue. What is true, and what I deeply regret, is that I tried to kiss the doctor. Nothing more happened.”

Peters’s narrative is most striking for what happened after the incident she describes:

The next day, the patient called and apologized. He said that he had a terrible problem and that he had done the same thing with many other women. That he basically couldn’t control himself when alone with a woman. I told him that he needed to get counseling immediately and to never allow himself to be alone with a woman in a room. I never directly heard from him again. However, he has become ever more powerful and venerated in his professional world.

A terrible problem, one that he couldn’t control: That is the language of pathology. And Peters’s advice—that the man get help and not allow himself alone with a woman—reads as a prescription. If the patient was indeed Moonves, the accusations reported by Ronan Farrow in The New Yorker clearly suggest what form the “terrible problem,” the putative compulsion, tended to take. In account after account, women in the workplace described Moonves unexpectedly grabbing them and/or kissing them, and then becoming cold and vengeful if they rebuffed him.

But the larger point of Peters’s tale is not simply that the incident happened. It’s that Peters was unable to do much about it because of the power differential involved. Patient confidentiality was one factor: “As a physician, I am legally unable to name the patient who harassed me.” And because the man was so prominent, she was discouraged by her employer from reporting the incident to the police. She considered placing a note in his chart for women not to be alone with him. Otherwise, she stayed silent.

If the patient was in fact Moonves, he would, allegedly, not take the doctor’s orders. Farrow reports two incidents in the 2000s when he cornered and harassed women. One of them, Deborah Green, was a freelance makeup artist who says Moonves forced a kiss on her when they were working together. When she rebuffed him, he told her to pack her bags and leave the office. She was subsequently not booked for any more jobs with CBS executives. “Knowing that Les is powerful is why I didn’t speak out at the time,” she told Farrow. “I was a makeup artist who had no voice.”

Power like Moonves’s can be used to silence in yet-more-direct ways, ways that don’t necessarily have to do with sexual harassment. Take for example the recently reported revelations about the infamous 2004 Super Bowl halftime “wardrobe malfunction” involving Justin Timberlake and Janet Jackson, which happened when Moonves was the head of Viacom. Jackson and Timberlake issued public apologies, saying the nipple reveal was an unplanned mistake that happened when Jackson’s bra “collapsed.” Timberlake’s career more or less continued apace, but Jackson faced long-term damage professionally. Awards-show invites were revoked, her new album was ignored by radio and TV programmers, and the woman who had been one of pop’s great trailblazers was made a national punch line.

According to reporting by HuffPost’s Yashar Ali, the lasting effect on Jackson’s career was attributable in no small part to a personal vendetta held by Moonves. After the halftime show, Timberlake reportedly apologized directly—and “tearfully,” Ali writes—to Moonves. By contrast, Moonves felt that Jackson was “not sufficiently repentant” to him. In retribution, he allegedly barred her from the 2004 Grammys, where she’d been scheduled to appear, and ordered MTV, VH1, and Viacom-owned radio stations not to play her music. Years later, when Jackson signed a book deal with Simon & Schuster—then part of Moonves’s portfolio—he was reportedly enraged. “How the fuck did she slip through?” he asked a staffer.

The reasons for Moonves supposedly blackballing Jackson were, according to Ali’s sources, rather personal: She didn’t repent correctly to him, whereas Timberlake did. But from the outside, the unequal fates of the two stars came to stand in for very broad social inequalities. Jackson, many fans and critics believed, was being shunted into the racist and sexist “jezebel” archetype. Her troubles were, at least, a sign that women couldn’t expect equal treatment.

“If you consider it 50–50, then I probably got 10 percent of the blame,” Timberlake himself said in a 2006 MTV interview. “I think America is harsher on women. I think America is unfairly harsh on ethnic people.” He was right about that. But Moonves’s alleged involvement puts a fine point on how it can be individuals—whose own biases and bugaboos can be amplified by their holder’s status in a hierarchical system—who perpetuate and feed such unfairness.

Other stories are emerging about Moonves freezing women out of the industry for mysterious reasons. Linda Bloodworth-Thomason, the creator of the hit sitcom Designing Women, writes at The Hollywood Reporter that she found herself serially sabotaged by Moonves, who’d reportedly hated the “loud-mouthed” characters of her show. Stars would express interest in her projects and then find themselves barred from above. Scripts would be praised and then killed. She suspected it was because she was peddling feminist material to an executive interested in, as she puts it, “macho crime shows featuring a virtual genocide of dead naked hotties in morgue drawers.” But even that was just a theory. “It was like a personal vendetta,” she writes, “and I will never know why.”

While the Jackson and Bloodworth-Thomason tales don’t involve harassment, they share much with the other stories being reported about Moonves. Accuser after accuser tells not only of the executive’s violations, but also of Moonves using his influence in the aftermath of those violations to deprive women of work. There’s Deborah Green, who lost jobs once she rejected him. There’s the former assistant Jessica Pallingston, whose attempts at stopping Moonves’s advances made him “cold as ice, hostile, nasty” and whose career in TV then “sort of fell apart.” There’s the actress and writer Illeana Douglas, who lost her sitcom gig after encounters with Moonves. “What happened to me was a sexual assault, and then I was fired for not participating,” she told Farrow.

Such allegations are, by now, sadly unsurprising in their contours. For the #MeToo wave has been, in large part, an accounting of grudges held by über-bosses of capitalist-cultural empires against the women who defied them. Ashley Judd saw her reputation slimed by Weinstein to directors and producers across Hollywood. Gretchen Carlson believes that Roger Ailes put a damper on her career when she pushed back against his abuses. When the server Trish Nelson quit her post at the Spotted Pig after the restauranteur Ken Friedman allegedly made a forceful advance on her, she “was terrified to tell anyone why,” as she told The New York Times. “Ken bragged about blacklisting people all the time. And we saw it happen.”

Blacklisting is, of course, an expression of control. It relies on the blacklister having immense influence and sway across an industry. That it is a tool of reprisal and silencing that enables sexual harassment is now clear. The Jackson story, however, also provokes the thought of yet-wider issues due for reckoning. Her difficulties were the subject of books and hashtag campaigns, yet Moonves’s personal role is only now emerging, which suggests just how easily campaigns of revenge can stay hidden. And that Moonves might still exit his post with a $100 million payout and an advisory role at CBS indicates how entrenched, how nearly untouchable, a figure like him can be.

All of which indicates that the accounting process nearly one year after Harvey Weinstein still has entire realms of abuses to touch on—realms that both do and don’t involve sex. How have barons of industry used their status in other questionable, petty, personal ways that worsen an indefensible status quo? How many careers—women’s careers, especially—have been destroyed for failing to show deference and obedience to a boss whose importance makes him or her seem invulnerable? Such questions hint at why #MeToo has been called a revolution: The movement may be modern, but it is drawing on very old lessons about the perils of power, unchecked.