‘6 Months Off Meds I Can Feel Me Again’

In tweets about abandoning psychiatric medication for his art, Kanye West promotes a dangerous myth about creativity.

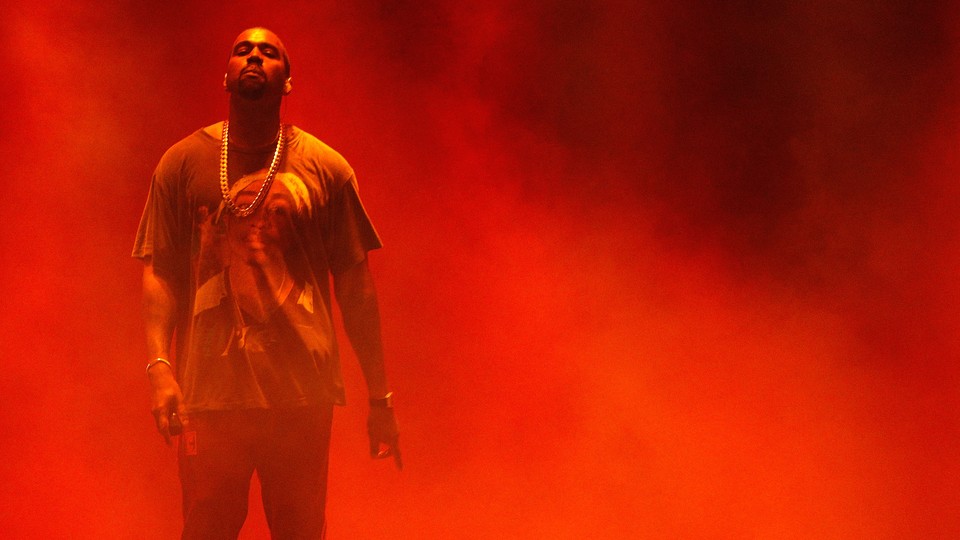

Kanye West has been tweeting again.

Last weekend, the always provocative rapper posted several dozen times on Twitter, which is often his public megaphone of choice. Many of the tweets concerned a topic that has been central to both his creative output and his public persona: his mental health. West, who revealed his diagnosis of bipolar disorder in 2017, declared he had been off his medication for six months, for the good of his music. “I cannot be on meds and make watch the throne level or dark fantasy level music,” he said in one tweet. My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy and Watch the Throne, a collaboration with Jay-Z, are two of West’s most beloved albums.

The tweets are part of a pattern of erratic behavior in the past year that has left fans concerned for his well-being. In June, he told The New York Times that he was “learning how to not be on meds” and that he’d taken medication only once in the previous week. In an October meeting with Donald Trump, West told the president that his bipolar disorder had been a misdiagnosis. Now, in apparently quitting his psychiatric medication for the sake of his creativity, West is promoting one of mental health’s most persistent and dangerous myths: that suffering is necessary for great art.

West may be the most recent public example of how this myth affects the lives of artists living with mental illness, but it has a long history that includes the struggles of people such as Vincent van Gogh and David Foster Wallace. Nevertheless, the notion isn’t logical, according to Philip Muskin, a Columbia University psychiatry professor and the secretary of the American Psychiatric Association. “Creative people are not creative when they’re depressed, or so manic that no one can tolerate being with them and they start to merge into psychosis, or when they’re filled with numbing anxiety,” he says.

Esmé Weijun Wang, a novelist who has written about living with schizoaffective disorder, has experienced that reality firsthand. “It may be true that mental illness has given me insights with which to work, creatively speaking, but it’s also made me too sick to use that creativity,” she says. “The voice in my head that says ‘Die, die, die’ is not a voice that encourages putting together a short story.”

Among people who deal with mental-health issues, it’s mostly people who experience mania—a sustained state of intense energy, racing thoughts, and elevated irritability—who complain that their medication makes them feel creatively blunted, says Muskin. That puts people with bipolar disorder, such as West, at particular risk for quitting medication. “I can understand wanting an internally directed high by the chemicals in your brain—that’s euphoria,” Muskin says. “You spend hours at the computer, and you feel like you’re writing something brilliant.”

What’s often not clear to people in the throes of mania is that although they might be superhumanly productive, that doesn’t mean what they’re producing is good. The way mania affects perception puts people who experience it in a particularly difficult position, explains Muskin: Despite its often negative consequences, to some people it can feel like a superpower, which might lead them to internalize the idea that their illness is the source of their talent.

Based on his work with patients, Muskin likens the experience of making art while manic to how brilliant people often think they sound while stoned: “You smoke with some friends and you record your brilliant discussion of Kafka or whatever. The next day, you listen to it and say, ‘Wow, we’re idiots.’” Not only does treatment not erase your creative abilities, Muskin says, but the correct combination of medication and therapy can make you more attuned to how your work’s quality will be perceived by people who aren’t in your mania with you.

Simon Kyaga, a researcher at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, echoed Muskin’s view of medication’s potential upsides for artists. “By reducing the risk for things like depression, medications may in fact increase the likelihood of being creative,” he says. He points to a 1979 study that found that lithium was a creative boon to people with West’s diagnosis. Any treatment that makes day-to-day life more livable and survivable for artists is good for their art, he reasons.

In 2012, Kyaga led a study of more than a million Swedes to investigate the connection between mental illness and creativity. His team found that creative people are more likely to have a psychiatric diagnosis of some sort, which means that the people treating them need to be sensitive to how treatment may interact with patients’ artistic processes. If treatment is mismanaged or medication isn’t prescribed appropriately, it can indeed cause problems for creativity. “I always stress the necessity to tailor treatment from an individual perspective,” he says. “This may sometimes mean adjusting the dose of medication or considering less well researched types of psychotherapy.”

Not all people with mood disorders need to or should be medicated, according to Muskin. But with all that researchers know about medication’s potential to help those who need it, why do so many people avoid treatment or quit it midstream? In the United States, at least, a big part of the problem for people without West’s resources is the inaccessibility of mental-health care. Many insurance plans don’t cover it. And that’s if you even have insurance—many people with psychiatric disorders don’t, often because mental illness can make it difficult to get a job. Even those with good insurance often face problems finding treatment because of the United States’ current shortage of mental-health-care providers.

Stigma against treatment is another big thing that keeps many people out of doctors’ offices. According to Muskin, the idea that medication’s aim is to obscure your truest self or make you a zombie can also encourage people who are on medication to quit altogether instead of seeking needed adjustments to their prescriptions. To them, he says, it can be easy to mistake the need for change for proof that their fears about psychiatric medication were correct: “The term is illusory correlation—it’s when you believe something, so you filter information to substantiate your belief and exclude everything else. We’re all vulnerable to it. We want to believe what we want to believe, and it truly prevents people from getting help.”

To Wang, the possibility of treatment means something good is on the horizon for creative people with mental illness. “The suffering makes for worse, not better, art,” she says. “Be excited about the art you can make when healthy.”