Uncovering the Roots of Caribbean Cooking

A lush book of recipes pays homage to the inventive culinary contributions of enslaved African women.

It has been said that enslaved Africans wore necklaces of seeds for good luck, seeds from the ackee plant, when they were forced onto ships’ hulls bound for the New World. Ackee, which is now known as the national fruit of Jamaica, is not indigenous to the land, but is native to western Africa. It made its debut in Jamaica in the late 18th century during a peak period of the British slave trade, which by its official end, in 1807, had brought more than 1 million Africans to the island.

Saltfish and ackee is one of the most popular dishes from Jamaican cuisine today. For those unfamiliar, ackee has a unique and earthy taste. It is a pear-shaped fruit whose skin ripens red, then opens petal-like, revealing three or four arils with black seeds atop each. As a source of protein, the fruit was essential for the survival of the women, men, and children forced to work grueling hours on the sugar plantations scattered throughout the Caribbean.

Salted fish was an imported commodity, too, from North America, and planters would occasionally share that bounty with their hungry slaves. African women, who were charged with arduous and unyielding labor on plantations, and who also had to generate sustenance for themselves and their families, mixed the leftover salted fish with ackee along with “Food,” shorthand for the prepared combination of starchy root vegetables like cassava, yam, and taro, which they grew and cultivated themselves. Saltfish and ackee represents the unseen labor of generations of women who, in the two centuries since the end of slavery, shaped how millions eat and survive in the Western Hemisphere.

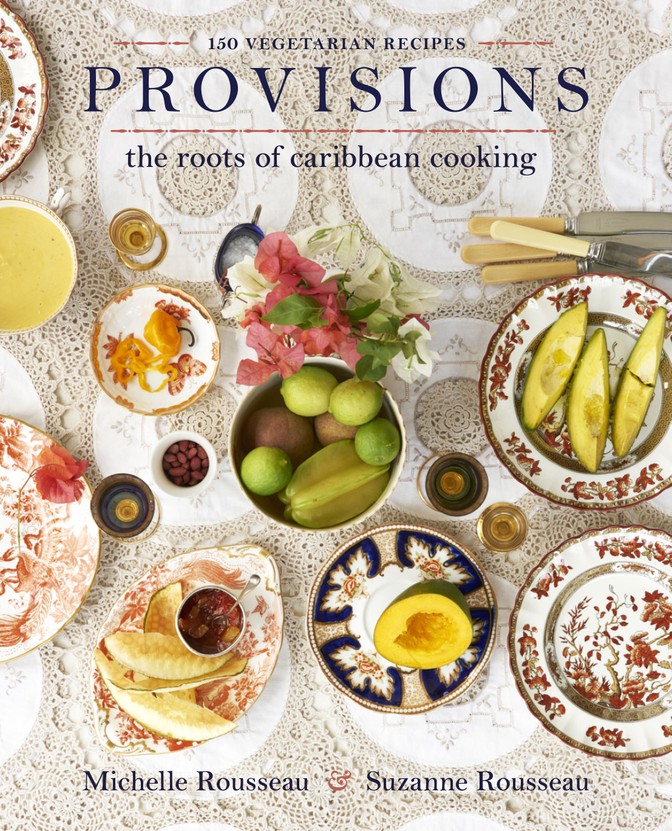

It is in this context that the sisters Michelle and Suzanne Rousseau situate Provisions: The Roots of Caribbean Cooking, a lush and artful work—one part cookbook, one part canonical and historical text. A modern collection of vegetarian comfort-food recipes, the book details the lineage of the invisible contributions of African women, and the savvy meal refinement of their descendants, self-reliant and creative West Indians who innovated the region’s most beloved foodstuffs.

The Rousseau sisters, who are both professional chefs, discovered through research of their own family stories that they are not simply outliers in their decades-long journey with cooking, entertaining, and entrepreneurship. Their path is, in fact, an inheritance. The sisters’ great-grandmother, Martha Matilda Briggs, began as a domestic and became a business owner, opening a café selling her much-reputed patties, baked black crabs, and pastries. She later expanded to a restaurant in the downtown district of Kingston, Jamaica, in 1936—an unusual feat for a single mother of seven during that time. Yet, Briggs was the embodiment of the resourceful creativity demonstrated by multitudes of Afro-Caribbean matriarchs, who had to innovate with meager resources to feed and sustain their families.

Provisions is bookended by deeply researched stories mined from the 19th century: journals once belonging to planters’ wives, rare narratives from enslaved women, and old cookbooks that give readers some sense of how Africans essentially made manna from heaven in the crucible of slavery. The Rousseaus draw a definitive line connecting the foods of survival from the past to their present iterations as delicacies.

Cassava, they highlight in the section covering recipes for ground provisions, is native to the region and similar to yam, a food familiar to African slaves. Yet, it was the indigenous communities of the Caribbean, the Rousseaus write, who taught early slaves “methods for its processing and consumption.” For instance, when cassava is grated and dried, it can mimic the qualities of flour. This dried iteration lends itself to bammy, a Jamaican flatbread made from “grated cassava that has been soaked in water, transferred to a cloth, and pressed to extract as much liquid as possible. The cassava is then flattened into a thick, disc-shaped flatbread and cooked over dry heat.” The sisters highlight this staple in their updated recipe for steamed bammy with coconut, pumpkin, ginger, and tomato.

Readers are also informed that plantains—ubiquitous in so many Caribbean dishes—did not originate in the area, but were also imported and planted everywhere to feed enslaved masses and supplement starchy provisions. In their modernized recipe for roasted ripe plantain with African pepper compote, the sisters write, “This knowledge has been passed down over generations, and it never ceases to amaze us how intricately connected we still are to our motherland, Africa … It is easy to see that the roots of our dining habits are deeply entrenched in a shared heritage with our ancestors from across the seas.”

Provision grounds, small tracts of the least desired land, were allocated by planters to slaves so that they could grow their own food for their survival. The planters conceded to this arrangement to avoid absorbing the expense of feeding the slaves they imported to power their sugar plantations. The deal only compounded the burdens of the enslaved—specifically the women, who were charged with duties that sustained the operations of the plantation (as kitchen cooks, servants, seamstresses, or field workers), in addition to being responsible for preparing meals for other parties. Yet this subterfuge lent itself to expedient invention.

And it had to. In the Caribbean of the 18th and 19th centuries, sugar cultivation dominated the region, spiking the demand for labor. Moreover, as the New York Times columnist Brent Staples notes, it was “an industry that earned its reputation as the slaughterhouse of the trans-Atlantic slave trade by killing more people more rapidly than any other kind of agriculture.” The enslaved were never really meant to survive. But on the backs of black women, they did. Through the sisters Rousseau’s mindful curation of foods that generations have come to cherish, readers learn more about how women created a life out of such brutality. Their names may never be known, but their epicurean knowledge passed around kitchen tables in times of feast or famine will endure for posterity.