When Demagogic Populism Swings Left

During the Great Depression, a Trumpian figure established unprecedented political control in Louisiana and attracted criticism for his autocratic methods—while pursuing a radical progressive agenda.

Here are three things you should know about Huey Long: He served as first the governor and then a senator for Louisiana in the late 1920s and early 1930s. While in office, he pursued a populist agenda by aggressive means that many critics saw as autocratic and unlawful. And he held on to popular support, in spite of the critics, right up until one of them killed him.

In an Atlantic article written two months after Long was assassinated in 1935, George Sokolsky remembered having asked Long if he was a fascist. “Fine,” Long told him in a conversation that took place less than a year before he was killed. “I’m Mussolini and Hitler rolled into one. Mussolini [force-fed dissidents] castor oil; I’ll give them tabasco, and then they’ll like Louisiana.” Then he laughed.

The accusation of fascism was nothing new for Long. He was a controversial figure in American politics, attracting a passionate base of support on one hand for effectively pushing progressive legislation and widely condemned on the other for alleged corruption and abuses of power. Rather than denying these allegations outright, Long tended to play them off, as he did to Sokolsky. “I used to get things done by saying please,” he said after the state senate tried, and failed, to impeach him in 1929. “That didn’t work and now I am a dynamiter.” Then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt regarded him as “one of the two most dangerous men in America.”

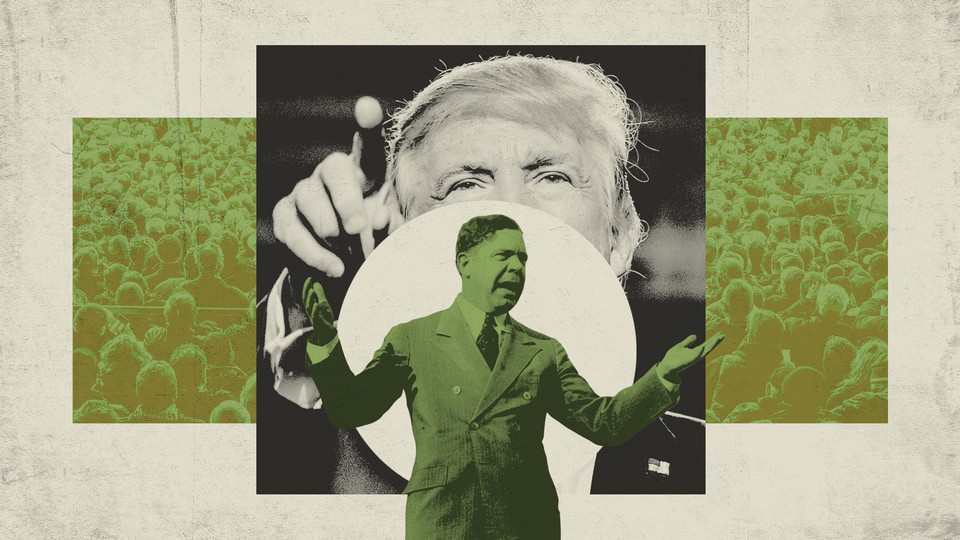

Few American politicians have provoked such devotion and recrimination at the same time. But Long has one notable modern counterpart: Donald Trump. In many ways, his final years paralleled Trump’s 2016 campaign and presidency. Both men rose to national political prominence in the aftermath of a global financial crisis, with ethnic violence on the rise, automation putting workers’ jobs in doubt, and autocratic leaders gaining political power worldwide. Both made waves with sweeping populist rhetoric and policy proposals that challenged their parties’ more moderate establishments and promised to make government work for the common people. Both encapsulated their pledge to elevate the nation in a catchy slogan: Trump’s “Make America Great Again” and Long’s “Every Man a King.” And both, once in power, showed little concern for norms and standard legislative procedures when pursuing their goals.

But while Trump ran on a reactionary brand of populism, blending anti-establishment rhetoric and promises to restore prosperity and order with appeals to racist and nativist anxiety, Long pursued a progressive agenda and steered clear of the race-baiting common in Southern politics at the time. In this sense, Long is an interesting foil for Trump, who registered as a Democrat at several points in his life and expressed support for some typically Democratic policies even as he turned to the right. Though he died before he could run for president, much less take office, Long’s brief political career provides a mirrored vision of Trump’s demagogic populism—a glimpse of what could happen if a left-wing politician channeled a similar message and disregard for political mores.

Much of the appeal of that kind of populism cuts across eras and party lines. Mark Brewer, a professor of political science at the University of Maine, identifies several factors that have led American populism to gain traction in certain moments, regardless of political affiliations: perceived conflict between “elites” and “common people”; a sense of economic unfairness; distrust of centralized authority, particularly the federal government; and a desire to “maintain a previously existing arrangement that’s under threat and, in a lot of cases, probably gone already.”

Throughout American history, he says, populist voters have felt “a sense of a loss of control about what was going on in their society. Things were happening and things were changing, and the change was unsettling, but they couldn’t do anything about it. It was almost like they were being acted on from above.” That feeling has engendered the rise of parties and leaders, conservative or progressive, that promise to fight the system on behalf of average Americans.

Huey Long pledged to do just that throughout his contentious political career, and often delivered. While Trump has most aggressively leveraged his executive powers to manifest the anti-immigration plank in his populist platform, introducing a “Muslim ban,” radicalizing ICE, and, most recently, declaring a national emergency in order to fund a border wall, Long used his authority to establish public works programs for the poor. In his four-year tenure as the governor of Louisiana, Long built an extensive network of highways and bridges through the isolated rural areas of the state, expanded lower-class access to health care and education, and implemented strict new regulations in the state banking industry that improved consumer protections.

After reaching the Senate in 1933, he pushed to implement a similarly progressive agenda on a federal level. Feeling that the New Deal was too moderate, he introduced a more radical alternative called the Share Our Wealth program, which would limit personal assets and earnings for the wealthiest Americans and redistribute money to guarantee a partial annual income to every family, fund old-age pensions for every senior, improve pensions and healthcare benefits for every veteran, and make a free college education and vocational training available to every student. Much of his vision remains an unrealized dream for progressives in the present day.

His efforts to fight poverty, rooted in his own lower-class upbringing, endeared him to poor voters and secured the support of his base from the beginning. “All the forces of the Federal Government … cracked down on him,” Sokolsky wrote. “He held because he gave people schools and roads and jobs and money; because he relieved the lower strata of the heaviest burdens of taxation; because he made it possible for the poor to vote. The sum total of Huey’s administration was that it accomplished something constructive.”

But in pursuit of those ends, Long worked to consolidate and expand his power by means that many felt were authoritarian. He gained a reputation for punishing political opponents early in his career, firing hundreds of bureaucrats and civil servants at every level of the Louisiana state government who didn’t support him and replacing them with people who did in the days after he took over the governorship. When politicians or institutional leaders opposed his agenda, he blocked funding and authorization for programs they wanted, ousted their family members from government jobs, and targeted them with retributive legislation. Incensed by negative coverage in the press, he founded his own newspaper. Later he co-founded an oil company, extending his powers of patronage beyond politics and into industry. Even after joining the Senate, he continued pushing bills through the Louisiana state legislature and retaliating against enemies and promoting supporters using his personal connections and state funding.

These tactics, Frank R. Kent summarized in a 1933 Atlantic article, “enabled Huey to win the battles waged against him, to save himself by a hair from impeachment, to elect himself to the Senate, to substitute a creature of his own to succeed him as Governor, to elect his personal counsel as his Senatorial colleague, to dominate all but one of the Louisiana House delegation, to force the publisher of one of the hostile New Orleans newspapers to eat out of his hand—in short, to reduce his opponents, who include the best people in the state, to a condition of complete impotence.”

Long was neither the first nor the last American populist leader to display authoritarian tendencies. In the 1830s, Andrew Jackson was dubbed King Andrew the First because of his liberal use of executive power. At the same time Long was amassing political capital, the Catholic priest and radio personality Charles Coughlin used his platform to promote fascism and racism to his listeners. In the 1960s, the Alabama governor George Wallace infamously blocked the racial integration ordered by the Supreme Court with his own body. Today Trump is attempting to circumvent Congress’s authority over the federal budget by claiming emergency powers.

For Long, those tendencies ultimately spelled a death sentence: He was assassinated at the age of 42 by the son-in-law of a political opponent he was attempting to oust from office. He never ascended to the White House. No progressive populist like him ever has.

But that might change. Even as right-wing populism has gained power in recent years through Tea Party politicians and Trump, left-wing populism has also resurged. Earlier this decade, Occupy Wall Street launched mass protests and popularized the dichotomy of the 99% and the 1%. In the 2016 presidential primaries, Bernie Sanders won millions of votes in a campaign fueled by small-money donors and full of populist rhetoric. Some of Long’s radical progressive goals, like free college and universal basic income, have become more mainstream within the contemporary Democratic Party.

“We don’t know where Long would have ended up,” Brewer says. “Certainly, the assassin’s bullet stopped him short of where he wanted to go.” Long was an aggressive and popular proponent of progressive ideas still less than halfway through his first term in the Senate; he could have pushed the Democratic Party further left, if he hadn’t made too many enemies along the way. As Sokolsky wrote, “Huey Long never could have been elected President of the United States, but he forced one President to adopt an absurd fiscal program, and succeeded in balancing the political scale so accurately that he was, after Franklin D. Roosevelt, the most significant political personality of his day.”

But he was also a staunch isolationist and an autocratic hoarder of power. As first World War II and later the Cold War and the civil-rights movement came to dominate American politics, the country’s populism grew more reactionary and nationalist. Gerald L. K. Smith, the man who co-founded the Share Our Wealth Party with Long, went on to lead the isolationist, racist, anti-Semitic, and anti-immigrant America First Party. Long’s abrupt and early death makes it unclear what path he would have taken, or what his aggressive brand of progressive politics would have looked like given more federal power, and more time.

If left-wing populism continues to gain traction within the Democratic Party, it could become more clear what that power would look like—with or without Long’s particular edge of authoritarianism.