College-Admissions Hysteria Is Not the Norm

A focus on highly selective schools obscures the experience of the vast majority of American undergraduates.

Every year at this time, headlines reveal once again what everyone already knows: America’s top institutions are selective—very. Harvard took a record-low 4.5 percent of the applicants to its 2023 class. Yale accepted 5.9 percent, the same as the University of Chicago.

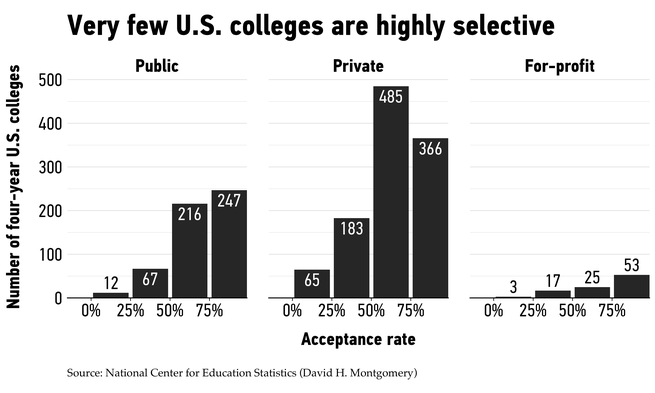

These numbers—albeit wild—are outliers, representing an almost-negligible slice of the United States’ higher-education ecosystem. Approximately 10.8 million undergraduates were enrolled in the country’s more than 2,500 four-year universities in the fall of 2017, according to an Atlantic analysis of raw figures from the Education Department’s data center.

The majority of students—more than 80 percent—attend schools, such as Texas A&M, Rutgers, and Simmons University, that accept more than half their applicants. In 2017, our analysis shows, roughly 3 percent of the country’s bachelor’s-degree candidates were enrolled at a four-year university that accepts fewer than a quarter of undergraduate applicants; only 0.8 percent of undergraduates were attending one of the handful of universities that accept fewer than one in 10 applicants.

Most schools are not these highly selective institutions, and the application process for millions of students is not the stress-inducing nightmare that gets so much public attention. Excluded from the narrative are the thousands of four-year colleges that serve millions of undergraduates, including many historically black colleges and universities—not to mention the 1,000-plus community colleges.

Various characteristics set these more-typical institutions apart from their brand-name counterparts, such as the fact that the former are more likely to enroll Pell grant recipients (read: very low-income individuals), as well as “nontraditional” students (that is, those who are 24 or older and/or have children of their own) and military veterans, according to the New America higher-education policy analyst Iris Palmer. They’re also less likely to be considered research universities—generally those that offer doctoral-degree programs—and more likely to be commuter campuses, according to Georgetown University researchers. Of all the country’s four-year institutions, slightly more than half are private, nonprofit schools, such as Massachusetts’s Endicott College and Texas’s Trinity University. About 29 percent are public—Mississippi’s Alcorn State University, for instance, and the University of California at Merced, near Fresno. The remaining 17 percent are for-profit, such as the College of Westchester in New York, and Oregon’s Pioneer Pacific College.

These schools dominate the options for most American high schoolers; attending them is a far more common experience than that provided by the Dartmouths and Dukes and Davidsons of the country. The landscape of higher education is far more sprawling than a focus on selective schools allows.

Moreover, the student bodies of the upper tier of competitive colleges are not representative of the demographics of the country at large. Research published by Opportunity Insights, a think tank led by the economists Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Nathaniel Hendren, has found that roughly three dozen of the country’s “elite” colleges—schools including Washington University in St. Louis, Trinity College (Connecticut), Tufts, Yale, and Brown—enroll more students from households in the top 1 percent of the income scale than they do students from the bottom 60 percent of that scale. In fact, students from the top 1 percent are 77 times more likely to attend “elite” colleges, here defined as schools that accept fewer than a quarter of undergraduate applicants, than are their peers in the bottom 20 percent.

Another often-overlooked feature of higher education in the U.S.: community colleges. Of the nearly 2 million bachelor’s degrees granted last year, roughly half of the recipients had community-college credit. In some states, a solid majority of bachelor’s-degree recipients at some point attended community college—in Texas, for example, the rate last year was three in four. In the fall of 2017, 5.8 million people were enrolled at community colleges, most of them as part-time students.

The most selective schools produce many of the people who populate the top ranks of American business, media, and political leadership. But the country is much bigger and more multitudinous. The work of educating its people falls by and large not to the small set of famous schools, but to the much wider array of ordinary schools, where millions of Americans go to learn every day.