The Other Notre-Dame Was Not Rebuilt

Perhaps France should help Haiti, its former colony, rebuild the cathedral lost in the 2010 earthquake.

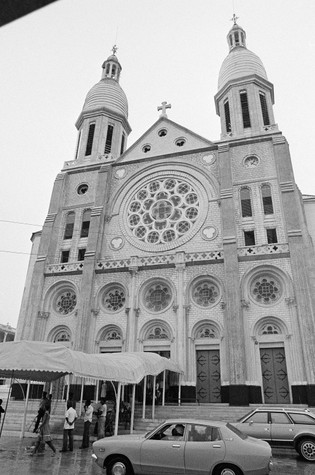

When I watched the fire consume the beautiful spire that for so long graced the roof of Notre-Dame de Paris, I was moved by the destruction, but also reminded of another partly destroyed cathedral, in a very different place, that still lies in pieces, forgotten: Notre-Dame de l’Assomption. The vaulting, overweening Haitian cathedral in downtown Port-au-Prince was brought to its knees in the earthquake of January 12, 2010. That huge seismic event killed hundreds of thousands of Haitians and also managed to knock down almost every government building and many of Haiti’s 19th- and early-20th-century Catholic churches, such as the cathedral, sending huge, heavy bells and shards of stained glass down into the city’s broad streets.

Ever since the earthquake, Haitians have imagined rebuilding this central structure of the capital. Some steps were taken early on, but as they say in Haiti: Epi? Epi anyen. “And then? And then, nothing.” Almost a decade later, I wonder whether Haiti really needs to invest in this symbol of a past era.

Unlike the French government, the Haitian government has been entirely absent from the discussion about reconstruction of the national cathedral, for many reasons. First, if someone else can be made responsible for the work and financial outlay on a project, then the Haitian government, which is usually poorer than, say, Bill Gates or Jeff Bezos, is going to let the other group do the job—in this case, the Catholic Church. Also, Haiti, infinitely more than France, has extreme and pressing problems that are far more serious than the rebuilding of some old building. Education, basic nutrition, health care, energy infrastructure, infrastructure tout court, sanitation. And, of course, security, as elections approach and gang violence escalates. Not that the Haitian government is doing anything much about those either.

Haiti doesn’t have a lot of billionaires hanging around, ready to take special charitable tax deductions by giving huge donations to rebuild the church. Nor is the Haitian cathedral a “world” building in the way that Notre-Dame de Paris had become. So when people saw Notre-Dame de l’Assomption in ruins on TV in 2010, they didn’t know what it had been before. As a piece of architecture and a monument, it had no real meaning outside Haiti; very few people outside Haiti felt it was a part of their lives as humans on the planet—unlike the cathedral in Paris, with its 13 million visitors yearly. Rightly, those who saw reports of the Haitian earthquake turned to more human-focused organizations and projects when they decided to make charitable donations.

Soon it will be a decade since the cathedral fell. Haiti’s archbishop at the time of the earthquake said that it might be 20 years or more before Haiti could put together the $30 million to $40 million necessary to rebuild the cathedral, and that he was eager for parishioners to be contributors, as they had been, to a degree, for the initial building of the church in the early days of the 20th century. But to the informed eye, Haitians in general are far more impoverished now than they were then, far more urban, far more dependent on a trickle of the faltering cash economy, so it’s hard to imagine them ponying up a percentage of their nonexistent income to rebuild the church.

Here’s one illustration of Haiti’s poverty: In Port-au-Prince, people eat spaghetti sandwiches, literally, white bread with white spaghetti in it. That’s starvation. These are not heaping, supersize American things on ciabatta with meatballs and gooey cheese and vegetables. They may, however, include ketchup. Haitians live in destitution that no one should experience. Income inequality is visible, public, and shocking. More shocking even than in Los Angeles, where I live, and where the homeless wander the streets and sleep under the freeway overpasses while … you know.

I’ve been reporting on Haiti for more than three decades, and last year the poverty seemed worse than ever, more unforgivable than ever. There are plenty of explanations for this and plenty of stakeholders, local and international, in the impoverishment of Haitians. The earthquake didn’t help, despite the optimistic chorus of outsiders, led by Bill Clinton, spewing verbiage about how Haiti would be built back better. As Graham Greene wrote so astutely in The Comedians, his 1966 novel about Haiti under François Duvalier, “It is astonishing how much money can be made out of the poorest of the poor with a little ingenuity.”

Unlike Notre-Dame de Paris, Notre-Dame de Haiti was not invented or designed by the people for whom it was built. With a small local economy, Haitians themselves rarely could dream of architecture on a grand scale (except for the Citadelle and the Sans-Souci Palace at Milot, both built with foreign help and in the days just after Haitian independence from France in 1804), and the cathedral, meant for worship of the Christian god, was not exactly in the Haitian tradition. So it wasn’t a statement of Haiti’s Haitianness—whatever that may be—as so many have argued Notre-Dame de Paris is of France’s Frenchness.

As a matter of fact, the Haitian cathedral, on which construction began in 1883—only 23 years after the Vatican deigned to recognize Haiti—was more French than Haitian. It was designed by a French architect, André Michel Ménard, who imitated many French cathedrals. The design even included late-Gothic-style rose windows of stained glass (pillaged and destroyed after the earthquake). At the time of its consecration, in 1928, the archbishop of Port-au-Prince was French, as was the rest of the Haitian hierarchy. When work on Ménard’s cathedral was completed, the building was the world’s largest structure made of reinforced concrete. No one knew what would happen to such a structure in the event of a shallow and powerful earthquake. Now we know.

Yet there was, and still is, a connection between the Haitian people and the ruined cathedral. Many Haitians were baptized there, took First Communion there, attended Sunday Mass. In the late 1980s, many parishioners who sympathized with liberation theology used the cathedral as a site for protest and for expression of popular feeling. I remember a group of young people staging a hunger strike on the altar of the cathedral.

In 1987, a hundred of them marched down the central aisle of the nave, lugging a sound system, and seven began a hunger strike. The kids, almost all 17 to 23 years old, had many demands for the Church hierarchy, foremost among them that Father Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who would later become the first freely and fairly elected president of Haiti, be allowed to remain in his parish—despite his continued preaching against the Church hierarchy and on behalf of the Haitian people and their right to a decent life. It was impressive to see a hunger strike in Haiti, where no one who can get food would ever dream of going without it for any reason.

Every day, the crowds of the curious in the cathedral grew larger. In the end, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church of Haiti was forced by this action to accede to the protesters’ demands. In a dramatic moment, the high clergy allowed Aristide, a tiny, bespectacled figure in white robes, rejected and hated by the hierarchy, to come into the vaulted sanctuary to end the hunger strike—to tumultuous applause and cheering from the thousands who packed the nave—and bring his people out of the cathedral, supposedly victorious.

The cathedral was a symbol, then, both of the dominant, French-influenced class and of the possibility for a democratic Haiti. It was also, most directly and obviously, a symbol of the power of the Catholic Church, which has been, since forever, one of the three formal pillars of Haiti’s culture and economy, the others being the government and the army. So, after the earthquake, there was at least a brief window when the Church brooded over how best to rebuild and restore this visible presence in the center of the country.

On Tuesday morning, I spoke to Segundo Cardona, the Puerto Rican architect who won a 2012 design contest for the reconstruction of the cathedral. With the Church supporting it, the competition was put together by Yves Savain, a Haitian American who was a force in Miami’s Little Haiti; the dean of the University of Miami’s School of Architecture; and the archbishop of Haiti, Guire Poulard. The jury included a Haitian architect, the editor of the magazine Faith & Form, a structural engineer, a liturgical consultant and designer from New York State, and Edwidge Danticat, the Haitian American novelist.

“The tragic fire [at Notre-Dame de Paris] brought me a lot of memories about the period in Haiti after the earthquake,” Cardona says. “I was very excited about the cathedral project, because I was very excited about church design and interested in the liturgy and the architectural relationship between the building and the liturgy.” He was eager to begin work, but the archbishop told him to be patient as he tried to promote the project.

In 2014, two years after he won the reconstruction competition, Cardona went to Port-au-Prince for the consecration of a new mini-cathedral, known as the Transitory Cathedral, which had been constructed next to the ruins of the old cathedral so Mass could continue to be said in the years before Notre-Dame’s reconstruction was finished. Cardona made the trip to show the congregation there his beautiful wooden model for the future permanent Notre-Dame. The model was stuck in customs for a while, as weird or valuable items tend to be in Haiti, but at the 11th hour, Cardona managed to get the model into the country and over to the temporary facility.

He felt his heart sink when he saw the neat, cheerful new building, where the Haitian Catholic clergy greeted him. He knew about it beforehand, of course, but it was different to see the church live. The Transitory Cathedral is a steel-frame, open-air space that seats 1,500, and its facade is modeled on a church where Emperor Faustin Soulouque, one of Haiti’s several monarchical leaders, was crowned in 1852.

The trim new church filled Cardona with foreboding. “When I saw this, I feared, and still fear, that the one we designed would never be built,” he said.

When you hear the word transitory or transitional in Haiti, you always have to wonder whether it means “final.” In any case, Guire Poulard, the archbishop who welcomed the idea of Cardona’s design, and Yves Savain, the Miami impresario who organized the competition and was so enthusiastic about reconstruction, are now both dead. Not an inch of ground has been broken, nor another penny spent beyond the $12,000 in prize money for the design contest.

The transitory space is plain and useful, and a breeze can blow through it when it’s hot out, which is most of the time, although in one of Haiti’s dramatic rainstorms or its annual hurricanes, the waters could drench it. For now, as Haiti continues to reel from the effects of an earthquake, hurricanes, and the global economy, a small space such as this one may be more fitting than a grand, soaring monument to the Catholic Church.

But if you know Haiti, you know that almost everyone from the richest person in the elite to the poorest countrywoman would like to be able to pray in a bigger place, sumptuously decorated with statues and symbols, that can accommodate all the Haitians who want to worship at their old site in something that resembles its former splendor. Just because a person is poor or of modest income doesn’t mean she wants to have poor or modest services. You should go to a Vaudou ceremony if you want to see how eager the average person is for costume, color, celebration, variety, liturgy, drama, and majesty.

Outsiders always want to convince Haitians that what Haitians want, architecturally, are modern, low-slung, open-air, eco-friendly, seismically sturdy national buildings made of indigenous Haitian materials. This was part of the gestalt of the international community in Haiti after the earthquake. But very few such buildings got built, in part because they are not, perhaps, to the taste of most Haitians, who might want something more substantial and imposing, and as good as or better than what everyone else has, and nationally important. Cardona’s new version includes seismic resistance and other changes, while keeping the grandeur of the old cathedral alive.

Never forget: first black republic, only successful slave revolution, earliest independence from the colonial power—which was France, by the way, and you could argue that Notre-Dame de Paris was built, at least during part of its years of construction and reconstruction, off the backs of slaves working for French masters. France’s wealth during the 17th and 18th centuries came in large measure from its hugely productive sugar plantations in Saint-Domingue (later Haiti). To say nothing of the approximately $21 billion (in modern dollars) that the newly independent Haiti was later forced to pay France over more than a century to avoid recolonization and pariah trade status. Maybe Haiti’s Notre-Dame de l’Assomption should get, as reparations from France, part of the millions raised for the reconstruction of Notre-Dame de Paris. If Haitians don’t have to pay to rebuild it, using money better spent elsewhere, then the cathedral, as a symbol, is probably worth rebuilding. A new cathedral isn’t all that France owes the Haitians, by any means, but it would be a beginning.