The Search for Progressive Judges

Activists have swept a new wave of prosecutors into office. Is the focus now shifting to the judiciary?

In 1989, when John Blount was just 17, he was convicted of a double homicide. Blount was sentenced to death, and later re-sentenced to life in prison without a chance for parole. While incarcerated, he started a mentoring program for kids, kept a nearly spotless disciplinary record, and got his GED. He was written up only once, for owning a contraband radio. In 2016, following a series of Supreme Court decisions deeming mandatory life-without-parole sentences unconstitutional for defendants under 18, Blount was made eligible for a resentencing. Before his resentencing hearing in 2018, his lawyer had worked with the Philadelphia district attorney’s office to negotiate a 29-year-to-life sentence. The judge, however, disagreed. “I cannot discount two lives,” said Judge Barbara McDermott after rejecting the negotiated sentence. “I believe in proportionality in a sentence.” Her sentence, 35 to life, will make him eligible for parole at the age of 52. (Blount’s attorney is now petitioning the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to consider the case.)

It used to be unheard of for Philadelphia judges to reject a negotiated sentence in these resentencings—until Larry Krasner, arguably the most progressive prosecutor in the country, took over the city’s district attorney’s office in January 2018 and started delivering on a promise to minimize incarceration. In response, several Philadelphia judges have shut down his attempts to keep people out of prison or release them earlier. Some, such as McDermott, have overruled resentencing agreements. Recently, some judges reportedly declined to consider an initiative, developed by Krasner, to seek shorter probation sentences.

After watching these developments with growing dismay, Rick Krajewski, an organizer for a leftist political group called Reclaim Philadelphia, convened about 30 Philadelphia activists in January at the offices of a prisoner-advocacy organization to float a radical proposal. Many of them had been instrumental in getting Krasner elected. But clearly, electing a progressive prosecutor hadn’t been enough. This time, Krajewski wanted to persuade them to spearhead a rare grassroots campaign for the typically sleepy judicial race.

This meeting birthed a coalition of organizations that collectively are raising public awareness about Philadelphia’s May 21 primary election and the judicial candidates running for seven open benches. Some are taking the unusual step of campaigning for candidates who share their progressive values. The coalition includes anti-incarceration advocates and activists for racial equity. Its platform includes eliminating cash bail, increasing sentences to rehabilitation-focused programs rather than prison, barring U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement from courts, and decriminalizing sex work and drug use.

Organizers also want to promote a more diverse judiciary that understands where defendants come from. “A big piece is, one, how are you treating the people who come before you? Are you humanizing them?” says Devren Washington, an activist associated with Black Lives Matter Philadelphia who is a lead coalition organizer.

Philadelphia voters first demonstrated an appetite for criminal-justice reform in 2015, when they elected Mayor Jim Kenney, who’d campaigned on promises to advocate for reducing the use of cash bail and give people with a rap sheet a more promising second chance. Since Kenney took office, the city won two big grants from the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge, totaling $7.5 million, to make the city’s criminal-justice system more efficient. (A grant from the MacArthur Foundation also funded the reporting of this story.) In the past four years, the city has cut its jail population by 44 percent.

Krasner, elected in 2017, came to office during a nationwide wave of reform-minded prosecutors: In Houston, Chicago, Brooklyn, and other left-leaning cities, prosecutors have been winning races on platforms to end mass incarceration. A prosecutor has tremendous sway when, for example, suggesting bail, negotiating plea agreements, and recommending sanctions for parole and probation violations. But judges and magistrates have the final say—and their decisions have been thrown into relief in jurisdictions that have elected reformist prosecutors. “What we are seeing is that the judges are deciding to take it upon themselves to be the obstacle for a progressive district attorney,” says Robert “Saleem” Holbrook, a former juvenile lifer who now works as a policy adviser at Amistad Law Project, a prisoner-rights advocacy organization.

Recently, justice-reform advocates in a couple of other places have also turned their eye to judges. In Harris County, Texas, which includes Houston, voters swept out the old guard to completely flip all 59 contested seats in civil, criminal, family, juvenile, and probate courts from Republican to Democrat; the new judges are preparing to stop detaining people accused of low-level crimes who aren’t able to post cash bail. Organizers in Texas are starting to scout for judicial candidates in Bexar County, which includes San Antonio, and in Dallas County, who support scaling back the use of cash bail.

In theory, judges should be impartial arbiters of justice, motivated by the law rather than politics. Since the birth of America, legal scholars and politicians have debated the best method to create an independent judiciary: Should it be elected, or appointed by other elected officials? That question has yet to be resolved, and currently each state institutes its own system for choosing local judges. However, the majority—87 percent as of 2015—of state-court judges are elected officials. “I think that the overwhelming majority of judges are trying to do their jobs in good faith,” says Alicia Bannon, the deputy director for program management of the Democracy Program at New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, “but those political pressures are real.”

Historically, that pressure has been applied by advocates for a more punitive justice system. The authors of a 2015 Brennan Center study analyzed television ads for judicial candidates nationwide and found that an increasing number of ads focused on how harshly the candidate would punish bad actors: In 2013 and 2014, a record 56 percent of campaign ads lauded tough-on-crime records or lambasted opponents for being soft. In the past, advocates on the left have lamented how these political pressures have influenced judges.

Now, the progressive activists in the Philadelphia election, and the ones in Texas, are unapologetically supporting judges whose politics align with their own. The primary election on May 21, rather than the actual election in the fall, will essentially determine who will win the judgeships, since the city’s electorate votes overwhelmingly for Democrats, leaving Republican candidates with little chance of victory. The primaries are technically partisan, but only one Republican is running. “The reality is no matter how you pick judges, they are going to be political,” says Jed Shugerman, a Fordham law professor who wrote The People’s Courts: Pursuing Judicial Independence in America. In today’s political climate, he says, progressive groups can have significant influence in left-leaning cities.

Pennsylvania is one of 39 states where some or all judges are elected. Still, judicial elections traditionally fly under most voters’ radar. Voters are influenced largely by how high a candidate’s name is placed on the ballot, which is assigned by a system of picking names out of a coffee can; they are also influenced to an extent by the Philadelphia Democratic Party’s endorsement.

The coalition is not the first to realize the need for more information about judicial candidates. An activist named Micah Mahjoubian became involved in Philadelphia’s judicial elections in 2001 when he served on the endorsement committee of a local LGBT Democratic club and was dismayed by how under the radar the judicial elections were. “I began to notice that we were so focused on the more high-profile races that we overlooked judges,” he told me. So in 2017 Mahjoubian created a centralized website, Philly Judges, detailing candidate information such as endorsements, answers to a questionnaire he’d sent the candidates, and links to campaign websites. Mahjoubian’s website came up first in a recent Google search for Philly judicial elections.

As a group, the coalition organizing around the upcoming judicial elections polled candidates on items such as whether or not they think Philadelphia’s bail system is fair; their thoughts on the “school-to-prison pipeline”; and the purpose of incarceration. “We want the entire apparatus of the criminal legal system in Philadelphia to be accountable to the people impacted by it—including both people who have suffered major harm and violence from crime, and people who have suffered from the harm and violence of mass incarceration,” says Hannah Sassaman, the policy director of an advocacy organization called the Media Mobilizing Project, which is part of the coalition.

Janine Momasso, a black woman who identifies as gay, told me she is running for judge in the court of common pleas in part because she is disturbed by the “cultural tone deafness” she has witnessed coming from judges during the decade-plus she has worked as a family-law attorney. She has witnessed judges chastise her clients for not speaking English, refuse to acknowledge transgender people’s preferred gender pronouns, and not be able to understand defendants who speak in an urban dialect. “When you have a homogeneous [group of] people adjudicating in a city that is majority-minority,” she said, “that is a problem.”

In mid-April, Reclaim Philadelphia released its endorsement recommendations, which most other member organizations in the coalition are also promoting; the list includes Momasso. Only one of the candidates was also endorsed by the Philadelphia Democratic Party.

Mahjoubian, who is not involved in the progressive coalition, doubts that its recommendations alone—or his website, for that matter—will be enough to sway voters, who are accustomed to accepting the Democratic Party’s slate. “I have not personally seen any one organization or slate take off in a way that has more of an effect than the party has,” he said. In his view, swaying the elections would take tenacious door knocking. Some of the organizations that now make up the coalition proved capable of this during Krasner’s district attorney’s race in 2017, but thus far, despite activists’ early efforts, the campaign to reform the judiciary is much less visible—judging from media appearances and lawn signs—than the Krasner campaign was.

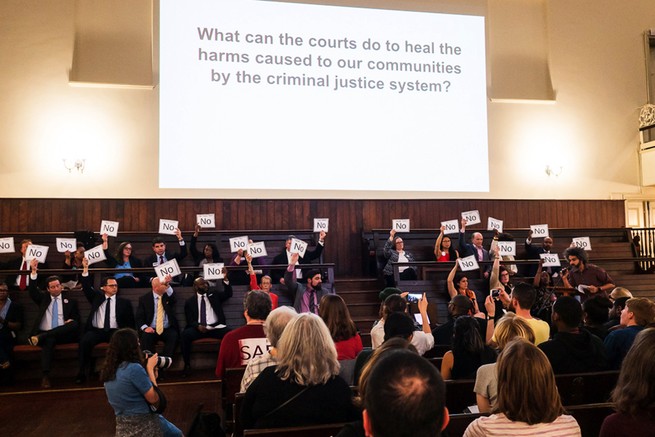

Still, the activists’ efforts seem to be resonating. About 250 voters turned up to a Quaker church in Philadelphia on a Monday in April for a forum planned by the coalition organizing around the judicial primary. Twenty-three of the 27 judicial candidates sat in the choir pews facing attentive audience members, some ready with a paper pad or a smartphone to jot notes.

“How many of you have stood in front of a judge?” Madusa Carter, a Reclaim organizer acting as the master of ceremonies, asked the audience. About a third raised their hand. Most of the questions for the candidates allowed for only “yes” or “no” answers. Then came an open-ended one: “What can the courts do to heal the harms caused to our communities by the criminal-justice system?” Not a single candidate pushed back on the question’s premise.

Cheyenne Johnson, a 22-year-old college student, attended the forum at the urging of a 29-year-old friend who has spent the past decade on probation. This was the first time Johnson had seriously considered which judicial candidates to vote for—not because she isn’t politically engaged, nor because she’s unfamiliar with the criminal-justice system. “I just never realized judges really campaigned,” she told me.

This article is part of our project “The Presence of Justice,” which is supported by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge.