Nothing Prepares You for Visiting Omaha Beach

The grief at the Normandy American Cemetery feels world-historical.

Editor’s note: Seventy-five years ago, Allied forces launched the offensive that signaled the beginning of the end of Nazi occupation of Europe. Ahead of the anniversary, our writer retraced their steps, and considered how a chapter that began with that effort may now be closing.

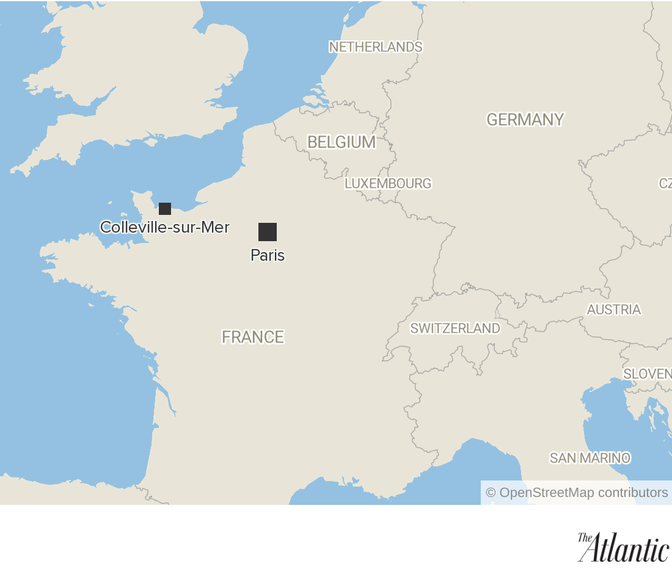

COLLEVILLE-SUR-MER, France—The first thing you notice, at the end of the narrow roads that lead to this precipice, is how peaceful this place is. The cliffs are thick with rough green vegetation and drop down—sharply, then more gradually—to a Prussian-blue sea and a windswept beach. Omaha Beach.

The morning I went, the sun was bright, and a few people were walking on the sand with a dog. I could see them from a lookout on the pathway to the Normandy American Cemetery here, where more than 9,300 servicemen and a few servicewomen are buried—neat rows of milk-white marble crosses, 150 Stars of David, and 307 graves of unknown dead that read, simply, “Here rests in honored glory a comrade in arms, known but to God.”

I had been told nothing quite prepares you for this place, and it was true.

June 6 is the 75th anniversary of the D-Day landings. In the past, American presidents have used D-Day to mark a moment—from Ronald Reagan, who gave his “Boys of Pointe du Hoc” speech at the 40th anniversary in 1984, at the peak of the Cold War, to Barack Obama, who addressed the 9/11 generation of veterans at the 70th in 2014.

This year’s commemoration, though, will likely have a different tone. Donald Trump, who will attend a ceremony here with French President Emmanuel Macron, has been threatening—in words as powerful as actions—the solidarity and mutual understandings of NATO. He’s been lashing out at Europe, accusing it of trying to rip off the United States, which has provided for the Continent’s defense since the Second World War.

But something else will be different too: Ceremonies are held every five years, and this will likely be the last time D-Day veterans will attend. It’s hard not to see this year’s ceremony as the end of a cycle of history—one that began with the Allies, led by the United States, turning the course of war here in Normandy and ended with the president of “America First,” who has made questioning the transatlantic alliance a pillar of his presidency.

“I always liken D-Day at 75 to 1938 in Gettysburg,” says Robert Dalessandro, the deputy secretary of the American Battle Monuments Commission, which maintains the cemetery here and many others around the world. In 1938, when the Civil War was just barely close enough to touch, President Franklin D. Roosevelt went to Gettysburg to inaugurate a memorial there. Invoking Abraham Lincoln, he spoke before veterans of the North and the South about how he was “thankful that they stand together under one flag now.” At the time, FDR knew that Civil War veterans would not live much longer, Dalessandro told me, adding, “In my heart, I know this is the last time we’re going to get D-Day veterans to this ceremony.” (This year, he said, about 35 D-Day veterans will attend.)

I had taken a strange, solitary pilgrimage here to begin to comprehend what had happened on these beaches in June 1944 after General Dwight D. Eisenhower—briefed on the weather and the winds and the tides and the tiny window in which such a massive, complex operation of air and sea and land and 150,000 troops could take place—gave his now-famous response, after less than a minute of reflection: “Okay,” he said, “we’ll go.”

And so they went. Anyone who has ever traversed this stretch of Normandy, the coast as it winds its way from Omaha Beach west toward Cherbourg, and understood the topography—the cliffs and the precious few routes inland meant the Allies couldn’t bomb heavily without risking being stranded on the beach—anyone who has ever set foot here comes away with two questions: How did these men pull this off? And what would have happened if they hadn’t?

Consider how many tens of thousands of individual decisions were necessary to achieve the cumulative effect of breaching the German defenses so enough Allied troops could pour into Europe to defeat the Nazis. At Omaha, the troops traversed more than 200 yards of beach, then had to scale 35 to 60 yards of cliffs, all while under enemy fire. Before the invasion, the Allies organized a misinformation campaign: Phantom field armies were planted; a group in Dover, England, tried to trick the Germans into thinking the invasion would be in Pas de Calais, not Normandy; an actor was hired to impersonate British General Bernard Law Montgomery to throw the enemy off course; planes dropped metal strips to scramble German radar, and leaflets telling the Germans their army was in retreat when it wasn’t.

Martha Gellhorn, the indefatigable reporter, managed to make the English Channel crossing to Normandy on a hospital vessel. She wrote about the chaos of the D-Day invasion, of the medical triage on the ship, and of small human moments in the middle of battle. “After that there was a pause, with nothing to do. Some American soldiers came up and began to talk,” she wrote. “Everyone agreed that the beach was a stinker and it would be a great pleasure to get the hell out of here sometime. Then there was the usual inevitable comic American conversation: ‘Where’re you from?’ This always fascinates me; there is no moment when an American does not have time to look for someone who knows his hometown.”

In all, about 225,000 service members were killed or wounded or went missing in Normandy from June to August 1944, including 134,000 Americans and 91,000 Britons, Canadians, and Poles, as well as 18,000 French civilians. The Germans lost more than 400,000 soldiers in Normandy. In La Cambe, inland from Utah Beach, I visited a German cemetery. The graves of the 21,000 dead are marked with flat stones, interspersed with a few clusters of thickly hewn crosses. A sign in English and French reads: “With its melancholy rigor, it is a graveyard for soldiers not all of whom had chosen either the cause or the fight. They too have found rest in our soil of France.”

THAT DAY AT THE AMERICAN CEMETERY in Colleville-sur-Mer, I spoke with Karen Lancelle, a guide here. Her family is from the area, and her grandfather donated some of the land for the cemetery. Sixty percent of the D-Day casualties are buried back home, in the U.S., and the remainder lie here. There is no order to the graves, not even alphabetical. Each name is carved into a kind of Italian marble known for its purity. Visitors take sand from the beach and rub it into the names, darkening each letter, until the rain washes it away.

Lancelle wore a navy-blue blazer and a red kerchief. She walked swiftly, purposefully, through the rows of graves. A silence hung in the air, punctuated by birdsong and the sound of our feet on the pathways. She showed me a photograph of Harold Baumgarten visiting a comrade’s grave in 2004. Baumgarten wrote about his experiences on D-Day and inspired one of the characters in Saving Private Ryan, the 1998 Steven Spielberg film that helped shape the popular imagination of the invasion.

For decades, the Greatest Generation veterans didn’t talk much about it. They went home and moved on. “These people gave us a chance. They bought time for us so we can do better,” Eisenhower told Walter Cronkite in 1964. It was Reagan’s speech on the D-Day anniversary in 1984 that began to focus renewed attention on the war. Between Omaha Beach and Utah Beach is Pointe du Hoc, a steep, narrow cliff that juts into the channel. A unit of 225 Army Rangers scaled this cliff in bad weather under enemy assault, and Reagan memorialized their efforts in his speech. Written by Peggy Noonan, it is a model of the form—stirring, poetic, and only 13 minutes long.

“We stand on a lonely, windswept point on the northern shore of France. The air is soft, but 40 years ago at this moment, the air was dense with smoke and the cries of men, and the air was filled with the crack of rifle fire and the roar of cannon,” Reagan began. He spoke of how the Rangers had scaled the cliff, and also of “a profound, moral difference between the use of force for liberation and the use of force for conquest.” That line reads differently today, after the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, where liberation has proved more vexing.

Reagan also spoke out against isolationism. “We in America have learned bitter lessons from two world wars: It is better to be here, ready to protect the peace, than to take blind shelter across the sea, rushing to respond only after freedom is lost. We've learned that isolationism never was and never will be an acceptable response to tyrannical governments with an expansionist intent.” Here, too, it’s hard to read these lines in 2019, as a president seems intent on taking American foreign policy down a different path.

Reagan delivered his remarks one year after his “evil empire” speech and three years before he implored Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall.” His Pointe du Hoc speech became a rallying cry against communism. He mentioned Warsaw, Prague, East Berlin. “Soviet troops that came to the center of this continent did not leave when peace came,” he said. “They’re still there, uninvited, unwanted, unyielding, almost 40 years after the war. Because of this, Allied forces still stand on this continent. Today, as 40 years ago, our armies are here for only one purpose—to protect and defend democracy.”

In 1994, President Bill Clinton also spoke at Pointe du Hoc, and marked a new generation. “We are the sons and daughters you saved from tyranny’s reach,” he told the veterans in attendance. In 2004, a year after the invasion of Iraq, President George W. Bush visited for the 60th anniversary of D-Day and ended on a religious note, saying that, along with life preservers and canteens and helmets, Bibles had been found on the beach. “Our boys had carried in their pockets the book that brought into the world this message: Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” (Reagan had died the day before, on June 5.)

When Obama came here to mark the 70th anniversary, in 2014, it was a different moment, with war still in the background—Russia had invaded Crimea just months before. Obama’s speech was longer, less poetic, more conversational than Reagan’s, and leavened with humor. “By 8:30 a.m., General Omar Bradley expected our troops to be a mile inland,” Obama said of D-Day. “‘Six hours after the landings,’ he wrote, ‘we held only 10 yards of beach.’ In this age of instant commentary, the invasion would have swiftly and roundly been declared, as it was by one officer, a ‘debacle.’”

Obama singled out D-Day veterans in the audience and also addressed a new group: “this 9/11 generation of service members,” he called them. “They, too, chose to serve a cause that’s greater than self—many even after they knew they’d be sent into harm’s way. And for more than a decade, they have endured tour after tour,” he said.

It’s anyone’s guess what Trump will say here on June 6, but I can’t easily imagine him saying, as Reagan said to America’s allies in 1984, “Your hopes are our hopes, and your destiny is our destiny.” Trump, who did not serve in Vietnam, has expressed contempt for the late Senator John McCain, who was held in captivity during that war. Trump is the president of a divided country, traveling to a divided continent, rife with internal divisions.

BEFORE THE NORMANDY INVASION, the War and Navy Department issued “A Pocket Guide to France,” with some useful vocabulary and a succinct analysis of the French character and mores. “They are not back-slappers. It’s not their way,” it said, and cautioned soldiers to be respectful of Frenchwomen and not to expect “modern American plumbing.” It offered this advice: “No bragging about anything. Bragging is never more than a means of offending someone. No belittling either. Be generous; it won’t hurt you.”

And then: “You are a member of the best dressed, best fed, best equipped Liberating Army of a former Ally of your country. They are still your kind of people who happen to speak democracy in a different language. Americans among Frenchmen, let us remember our likeness, not our differences. The Nazi slogan for destroying us both was ‘Divide and Conquer.’ Our American answer is ‘In Union there is Strength.’”

After my tour of the D-Day beaches, I downshifted through small towns and roundabouts—one had some “yellow vest” protesters—and followed the highway back toward Caen, past stands of trees and signs that warned of a risk of hydroplaning on the flat stretches. Unlike Bayeux, which stands largely intact—the Bayeux Tapestry is a stunner—Caen was bombed to near-oblivion during the war and was rebuilt, not terribly handsomely. From there I took the train back to Paris. It’s so easy now to travel a route that once required a conquering army. Out the window was Normandy—the green fields, the cows, the gray sky, the driving rain.

When I got home, a thick sadness descended, and wouldn’t lift for days. Cemeteries bring back ghosts. But the sadness, or grief, was also world-historical. I kept thinking about the steep cliffs, the wide stretches of beach, the rows and rows and rows of graves. My trip to Normandy had left me with an unsettling feeling that the postwar world—the world of the Marshall Plan and NATO and international alliances that a lot of us grew up believing were unshakable—is fragile. That it may even be over. What has replaced it has not quite taken shape, but it is a world of small leaders and blustery autocrats. I wonder, I truly do, what the veterans of D-Day make of this new world. I will think of them on June 6, and you should too.