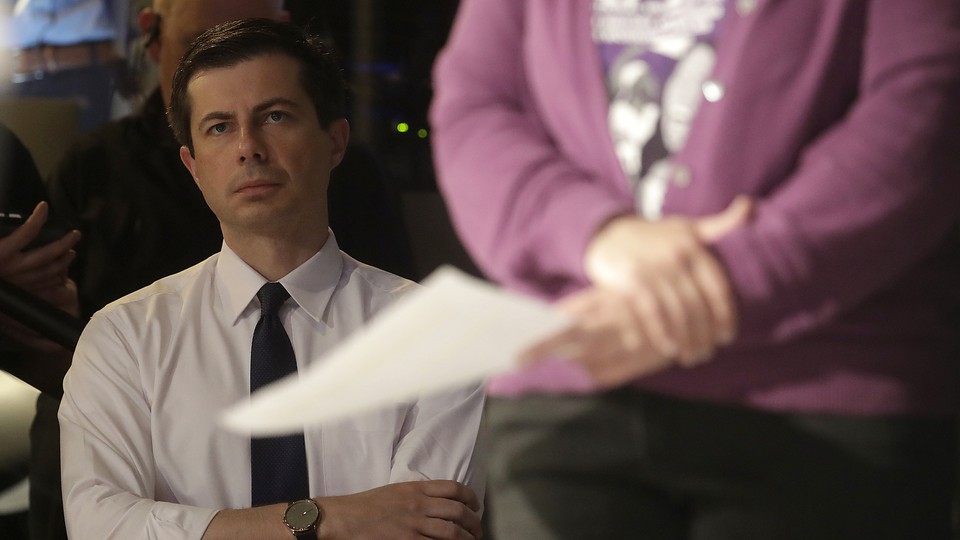

Pete Buttigieg’s Crash Course in Crisis

For all those nationally who’ve been dazzled by the mayor, the voters of South Bend aren’t satisfied with his response to a fatal police shooting last week.

NORTH AUGUSTA, S.C.—The metaphor was so obvious, even cliché, but it was also inescapable: As Pete Buttigieg was driving here from Columbia for a town hall late Saturday afternoon, huge, dark clouds moved into the sunny sky, and a cold wind started blowing through the heat.

“We’re hoping to beat the rain,” Buttigieg told me over the phone, looking out the window, as the crowd and I were waiting for him to arrive. “Looks like something biblical is happening here.”

The South Bend, Indiana, mayor has had the most charmed rise of any 2020 candidate. Given the leap he’s made from an obscure small-city mayor to a top-tier presidential contender, his is arguably one of the most charmed political ascents ever in American politics. Yet there’s been no charm to the past week of his campaign. Back home, a white police officer’s fatal shooting of a black man armed with a knife has exploded years of built-up racial tension in the city. And for all the people nationally who’ve been dazzled by his knack for offering answers that seem to fit problems like puzzle pieces, the voters back home don’t seem satisfied by what the mayor has come up with so far.

“When you’re in charge of the city, you know that any given day, things can come up and will come up that you have to answer for, first as mayor and then also in the context of the campaign,” he told me. He was never expecting the worst-case scenario of the past week to actually happen, though.

Running for president means running to be the one who gets stuck dealing with the nation’s worst crises. I asked him how the shooting and its aftermath have affected his thinking about sitting behind the desk in the Oval Office. “You’re handling an incredibly difficult situation where you’ve got a grieving family looking to you for answers and accountability; you’ve got a police department looking to you for leadership,” he said. “You’ve got to step into that in a way that shows you’re not thrown, you’re not rattled, that you care. [And] that no matter how much you care, it’s not going to throw you from taking the time to do the work and understand what’s at stake.

“You learn from everything that happens, and you especially learn from tough times,” Buttigieg added. “This has given me, already, a different grasp of what’s at stake in an issue that should be talked about by presidential candidates.”

Buttigieg has pitched himself as a mayor who has to provide actual solutions for his constituents—not just talk about problems. But many in the city’s black community in particular have protested his response to the shooting. He’s noted that he’s not legally allowed to fire police officers, as some voters have urged him to do. Though he said he plans to request a Justice Department review of what happened, under pressure, he admitted he doesn’t know whether officials will agree to take it up. Local leaders complain that Buttigieg is paying the price now for not investing more effort over time in police reform and community building, and that much of the outrage tracks back to the firing of an African American police chief in his first term.

The crisis—exacerbated by rage at the officer for apparently not having his mandated body camera turned on and at police for taking the victim, 54-year-old Eric Logan, to the hospital in the back of a police car instead of an ambulance—wasn't helped by Buttigieg's decision at the beginning of last week to meet with police for more time than he spent with the family. Some in the community saw the move as prioritizing law enforcement.*

After spending most of his time outside South Bend as his White House campaign took off, he’s spent more consecutive days at city hall in the past week than he has in months. If not for the shooting, he would have spent a chunk of last week on a glitzy fundraising swing through California that would have included an event at the home of the Hollywood power agent and mega-donor Michael Kives; so-called Champion tickets were going for $2,800 apiece, and Advocate tickets for $1,000, according to an invitation forwarded to me.

Buttigieg’s Saturday, as a presidential candidate, and his Sunday, as a mayor, couldn’t have been more different. He got huge cheers as he took the stage at the South Carolina Democratic Party Convention in Columbia, and the crowd quietly listened as he reflected on Logan’s death. “It is as if one member of our family died at the hands of another,” Buttigieg said. With solemnity, he said he knows why “such deep wounds are surfacing” in South Bend, before he glided into his practiced stump speech. (The bridge: “When a city is challenged, just as when a nation is challenged, the most important thing you can fall back on is your values.”) A few hours later, he ran onto the stage, microphone in hand, as the crowd at his campaign town hall cheered, and he was mobbed afterward by people asking for selfies and hoping he’d autograph their copies of his memoir.

The next day, Buttigieg was booed and shouted at while sitting onstage in a high-school gym in South Bend, where he and the police chief held a town hall. One man yelled that Buttigieg seemed like he had to run back to South Carolina instead of doing his job there. The mayor told the crowd he accepts responsibility for what happened: His administration runs the police department; his administration had bought the body cameras. By the time he spoke to reporters afterward, there were tears in his eyes.

But for the most part, publicly and privately, Buttigieg has tried to respond to the shooting with the same calm and analytic approach that, in other circumstances, his fans outside South Bend have found so appealing—but that critics feel can come off as the detached, someone-should-do-something air of a McKinsey management consultant, which Buttigieg briefly was in his 20s.

When I asked him on Saturday about the shooting, he said, “I really believe that if we don’t conquer racial inequity in my lifetime, it may be the thing that unravels the American project in my lifetime.” Still, when he was asked by a voter, at his campaign town hall, what his biggest surprise has been on the job, he said learning how to manage the plows during the big snowstorm that hit on his first day as mayor eight years ago.

“This is something that’s had an impact on our campaign, on me personally, and, most importantly of all, on my community,” Buttigieg told me in our interview. “This is a reminder that things come at you that you can’t always fully prepare for and can’t anticipate. And you need to be ready for that, especially as you’re competing for the toughest job in the world.

“It’s exceptionally serious compared to most things that we’ve dealt with. And, of course, it is different when you have national attention,” Buttigieg added, noting that some community members want to use the attention from his campaign to make sure that the city handles the shooting’s fallout in the right way. “They’re basically saying, ‘We have to get this right, not only for us, but because everyone’s watching,’” he said.

This all comes as Buttigieg has been struggling to attract African American support; of the more than 350 people who came to his campaign town hall on Saturday, the majority appeared to be white. The crisis is also unfolding in the middle of the most intense two weeks of the primary campaign so far: with major state-party political events and a Planned Parenthood forum over the weekend in South Carolina, the first debates this week, and a fundraising deadline on June 30 that his campaign hopes he’ll meet with an outrageously high number. The fundraising events he missed in California likely could have netted him a few hundred thousand dollars, if not more.

But between debate prep and big-dollar fundraisers, Buttigieg has been flying back to South Bend on a charter plane. A few hours after he landed from South Carolina, there was another shooting in South Bend, this time at a bar, with 10 people injured and one person killed.

“One of the reasons why most mayors don’t run for president—it’s because the heat gets put on them,” said Oliver Davis, a South Bend councilman who has been a local leader on policing issues and who in the past week has become one of the main sources for reporters of quotes challenging Buttigieg’s leadership. “There’s no magical speech that can solve this,” Davis told me. “This is a process that is going to be dealt with on his watch.”

A sliver of Buttigieg’s earlier luck has stayed with him. All week long, cable segments about South Bend were bumped by ones on Joe Biden’s comments about working with segregationists in the Senate, according to people I spoke with who were on cable-news sets in recent days. And the rain in North Augusta held off long enough for Buttigieg to finish his speech and all his selfies.

But what Buttigieg is facing here is nowhere near over. The anger has only grown. The police review hasn’t happened yet. He is expecting months of lawsuits ahead. And the real action of the presidential campaign is only just beginning.

* A previous version of this story stated that, after the shooting, Pete Buttigieg met with police before meeting with Eric Logan's family.