The Most Compelling Photo of the Moon Landing

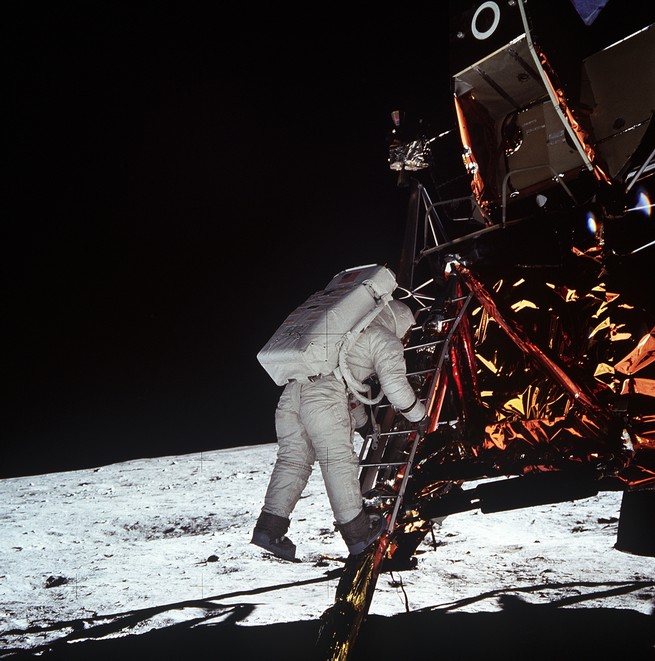

As Buzz Aldrin descended the lander’s ladder, Neil Armstrong captured the moment.

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a series reflecting on the Apollo 11 mission, 50 years later.

For 18 minutes and maybe 19 seconds, only one human being had ever set foot on the surface of the moon. Neil Armstrong made his famous one small step, and then started unpacking the most important thing the astronauts brought with them: a 70-mm color camera.

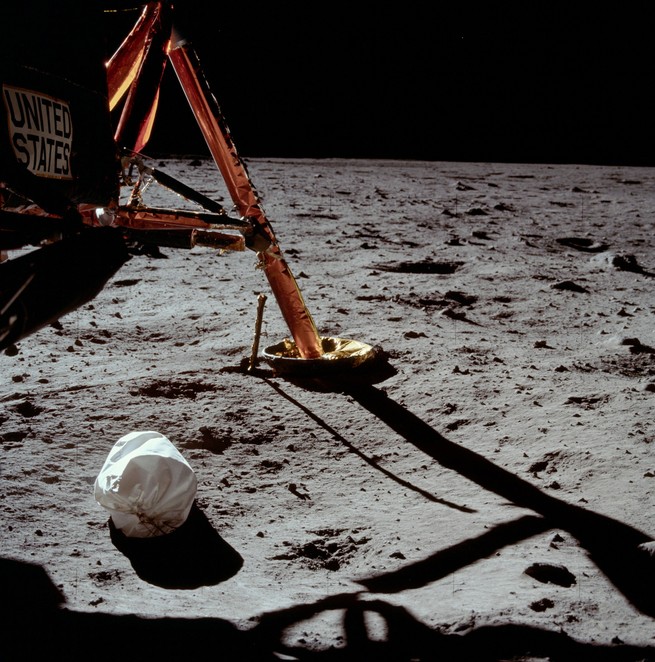

Armstrong’s first shot, per the instructions taped to his wrist cuff, showed the landing area, including one leg of the lunar lander Eagle. He pivoted to take a panorama, showing the terrain where he’d touched down as the spacecraft burned precious fuel. He was so caught up in the first moments of moon-based photography that mission controllers in Houston had to keep reminding him to collect some moon samples, in case he and Buzz Aldrin had to evacuate suddenly.

Once Armstrong had some moon bits safely stowed in his pocket, Aldrin finally prepared to get out and join Armstrong on the surface. Aldrin clambered through the Eagle’s hatch and onto a ladder with its last rung hanging about three feet above the lunar surface. And Armstrong snapped this photo.

It’s not the most famous photo from Apollo 11, nor from Buzz’s brief jaunt on the moon. That distinction probably belongs to the one of him saluting the flag, or the one of him facing the camera, legs bowed open, with Armstrong’s reflection in his helmet visor. But the picture of Buzz descending to the moon’s surface is the most compelling, in my view.

It’s not posed; it’s in no way a passive picture. Aldrin is moving; he is descending—he is alighting. He’s holding on, letting go, almost there, leg out, just about to leap down. He is on the cusp of transforming the moon into a place that humans, plural, have walked upon.

This picture brims with meaning: Someone took it. Someone else was already there, is unseen but known to the viewer, and we are seeing this moment as he saw it. “A portrait is not made in the camera but on either side of it,” as the early-20th-century photographer Edward Steichen put it. A photo’s existence implies the photographer’s, too. The moment really exists among three parties: the subject, the photographer, and the audience. And in this moment, all three are on the moon—the vantage point is so clearly from this other place that it places the viewer there, too, for the first time.

I have often thought about the weird profundity of this scene. Armstrong’s small step was momentous, and I have watched the grainy video footage of his descent more times than I can remember. But to me this photo reflects an even more consequential shift. With this perspective, everything changes. It’s the perspective of there, of the already arrived. Until this photo, every image of the moon, in our minds and in our cameras, had been from the other vantage point—from far away, looking up. On the outside, looking in, if you will.

Now one of us was there, on the inside looking out. The human mind was inhabiting the moon, rather than projecting onto it. A human presence was welcoming another visitor.

It is rare, even in an exercise as mind-warping as space exploration, to experience a moment like this. There is one person I regret never asking about that frisson, because he is the subject of the only other image that holds this sort of power, and he was part of Apollo 11, too.

Bruce McCandless served as mission control and capsule communications, “Capcom,” during Armstrong and Aldrin’s moonwalk. McCandless was famously peeved that Armstrong hadn’t shared what he’d planned to say when his boots touched lunar soil. Fifteen years later, McCandless would set a record for the greatest distance an astronaut has ever traveled from a spaceship. While wearing a jetpack during a mission of the space shuttle Challenger, McCandless ventured 320 feet from the shuttle without a tether. “It might have been a small step for Neil, but it’s a giant leap for me,” he said.

The photo of McCandless’s leap is haunting and beautiful in its own right, but one reason it’s so appealing, at least to me, is because it’s also evocative of the people McCandless left behind. The people watching him were the astronauts Vance D. Brand, Robert L. Gibson, and Ronald E. McNair. (McNair would perish on that same ship two years later.) McCandless seems so very alone, floating far above the world, and yet through this image, we are with him. I always wish I’d asked him about that before he died, in December 2017.

And oh, do I wish I had met Neil Armstrong. I tried, and my dad tried for me, when I was young. Instead I have a signed photo, mailed to my childhood home in response to a plea to have him come speak at my school. That photo now sits in my office.

I would have had a lot of questions for Neil, but especially in more recent years, I absolutely would have asked him about the Buzz-on-the-ladder photo. Did he think about what it meant? Was it significant to him at all? Did he feel alone, or frightened, during that 18-minute stretch of time, and did this photo bring relief along with it? What was it like to be a one-man welcoming party for the only other place in the universe humans have ever touched?

After Armstrong snapped the image, Aldrin leapt down, then tested jumping back onto the ladder and down again. Finally he joined his crewmate.

“Beautiful view!” Aldrin said.

“Isn’t that something! Magnificent sight out here,” Armstrong agreed.

“Magnificent desolation,” Aldrin said.

For the rest of the mission—the two were on the surface for only three hours—Armstrong eschewed being the subject of photos, instead taking snapshots of the more hammy Buzz. As the space historian Robert Pearlman describes it, this wasn’t necessarily because Armstrong was camera-shy (though he grew more reclusive in his later years). Rather, he was just following the checklist, which called for him to hold the duo’s camera. (Another one stayed on board the lander as a backup.)

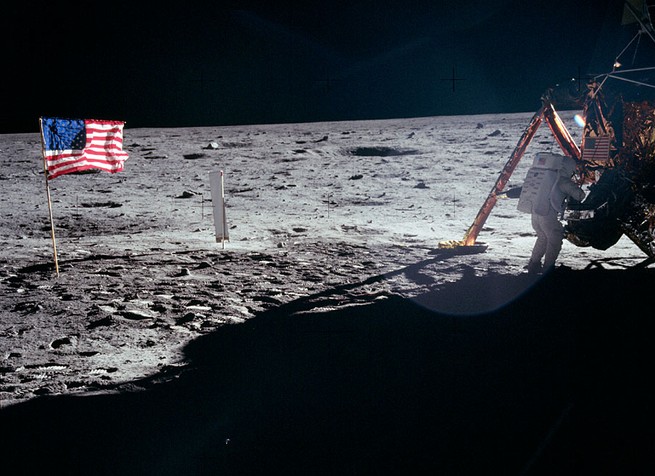

As a result, only one full-body photograph of Armstrong was taken on the moon, a fact I find shocking to consider. Neil Armstrong’s first step is immortal, yet we barely have a picture. The snapshots most people see, the ones on postcards and artwork and memorabilia, depict the second moonwalker, not the first. And in the only full photo of Armstrong, his back is to the camera. Aldrin took it as part of a panorama series, and it almost seems like an afterthought.

I like that photo a lot, too. It captures a man I worshipped as a kid, but it also represents another seismic shift, again thanks to the Hasselblad camera of Apollo 11. Aldrin happened to catch Armstrong in the frame simply because the first man was performing some boring task. Photography on the moon began with a profound change in perspective, and a couple of hours later, it was already capturing a mundane scene, as if life on the moon were nothing special.