Hong Kong’s Protests Have Cemented Its Identity

Chinese authorities have long sought to sway Hong Kongers, but more and more, residents of the city see it as being distinct from the mainland.

HONG KONG—As political upheaval here rolls through the summer, the proposed legislation that set months of demonstrations into motion has faded considerably from the prominence and parlance of protesters.

Instead, disquiet over the now shelved bill, which would have allowed for case-by-case extraditions to mainland China, has morphed into something deeper, unearthing grievances and demands far beyond any single piece of legislation, and opening up a wide-ranging conversation over the fundamental question of what it means to be from Hong Kong. Protesters have laid out five demands for the government to bring their demonstrations to an end, but imbued in their fight is a sense that Hong Kong’s very existence and the identity of its people is being deliberately quashed by authorities who want to tie them closer to China.

For more than two months, huge numbers of Hong Kongers have taken to the streets in mostly peaceful rallies demanding that their freedoms be protected. Today, undeterred by a downpour and only limited permission from police, some 1.7 million people again flooded the city’s streets, according to the Civil Human Rights Front, which organized the demonstration.

And as those protests have continued, participants have taken particular aim at symbols of the mainland: When a group stormed Hong Kong’s legislative assembly last month, black spray paint was used to cross out references to the People’s Republic of China; a group of protesters was arrested this week for tossing a prominently displayed Chinese flag into the city’s main harbor. These efforts have also veered into acts of mob violence tinged with paranoia. Demonstrators at Hong Kong’s airport last week held captive two men—one, a suspected police officer from mainland China, was held for hours and mocked as he faded in and out of consciousness; the other (later revealed to be a reporter for the Chinese state-backed newspaper, Global Times) was zip-tied to a baggage cart.

“Hong Kong identity isn’t just based on the rejection of Chinese identity, but a collective sense of resilience and autonomy and saying no to oppression,” Johnson Yeung, a veteran activist and former student leader who was arrested during a protest last month, told me. “Hong Kong people are putting up a fight to save their unique status.”

Yeung’s sentiments are reflected across the territory, especially among the young. A University of Hong Kong poll in June, when these latest protests began, found that 75 percent of people ages 18 to 29 identified as “Hong Konger,” as opposed to “Chinese,” “Chinese in Hong Kong,” or “Hong Konger in China,” the highest proportion since the poll began tracking identity sentiment, in 1997. Overall, 52.9 percent of respondents across all age groups identified this way, according to the survey, up from 35.9 percent in 1997.

(The term Hongkonger was itself added to the Oxford English Dictionary only in 2014 and is defined as “a native or inhabitant of Hong Kong,” though a common spelling style has not yet been agreed on. Both Hong Konger and Hongkonger are prevalent. Shirts with the dictionary entry printed on them are sold in gift shops and have been a common sight at recent protests.)

Much of the organizing of demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience has taken place on the encrypted messaging app Telegram. In one of the many protest-related groups on the app, I put a question to users: “What does being a Hong Konger mean to you?”

The first responses came within a few minutes and continued for days. Nearly two dozen people—frontline protesters, Hong Kongers living abroad, students—sent back messages detailing their thoughts. Some were succinct (“We are not Chinese,” one 40-year-old man wrote), while others sent lengthy paragraphs. One related his sadness that his young son would grow up to see a city fundamentally different from the one that he experienced; another said she thought Hong Kong’s films, which blend humor and traditional Chinese themes, best represented the territory; a man in his 20s talked about recently becoming enraptured with Hong Kong history and digging through old maps of the territory; some poked fun at the stereotypes of Hong Kong people as buttoned-up workaholics focused on money.

All spoke with immense pride for Hong Kong and its community spirit—and nearly all told me that the recent protests had served to harden their position of being distinct from the mainland.

“This anti-extradition-bill movement enhanced my Hong Kong identity, where I saw Hong Kongers’ unity and how high quality Hong Kong people were,” said one protester, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals from the authorities (another by-product of the protests has been a growing unease among demonstrators with identifying themselves in articles or photographs, despite this city ostensibly having a free press and the right to protest). This demonstrator spoke of being deeply moved by protesters helping one another with supplies and organization over the past months: “How can you not love this place when you see people unselfishly helping each other?”

The genesis of the Hong Kong identity as separate from the mainland can be traced in part to China’s internal developments, said Steve Tsang, the director of the China Institute at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies and the author of several history books on Hong Kong. Before Mao Zedong came to power in 1949, the border between Hong Kong and China was essentially open, and there was a free flow of people between the southern mainland and Hong Kong, Tsang told me. But once Mao took over, a border was enforced between Chinese Communist Party–controlled territory and Hong Kong, which remained a British colony until 1997, thereby creating a population that, as Tsang told me, “would grow up and expect to die in Hong Kong, which was not what happened before 1950.”

The coming decades produced the first generation of Hong Kong residents largely cut off from the mainland. As the city developed and incomes rose, the mainland languished. When China began to open up, people in Hong Kong “had a chance to go and see China at the tail end of Maoism,” Tsang said. “They crossed the border and really didn’t like what they saw. They went back to Hong Kong, and they realized that ‘yeah, we are kind of Chinese, but we are not that type of Chinese—we are Hong Kong–Chinese.’”

In 1997, when Hong Kong was handed back to China, beginning a 50-year period when it would maintain its freedoms but be ruled by Beijing, there were high expectations among mainland authorities that “identification with the Chinese nation would slowly but surely strengthen among the local population,” Sebastian Veg, a historian at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences in Paris, wrote in a 2013 piece.

But, Veg cautioned, “the end of the resistance to colonialism may have paradoxically weakened the feeling of cultural belonging to the Chinese nation. Simultaneously, a new resistance to Beijing’s fixation on patriotism emerged. Most importantly, however, the new generation may be growing more aware of a contradiction between patriotic and democratic values.”

In the six years that have passed, Veg’s observation, made before even the 2014 Umbrella Movement protests in Hong Kong, looks prescient. Beijing has ramped up its efforts to pull Hong Kong more firmly into its control. Infrastructure projects linking the mainland to Hong Kong have sprung up, despite vocal opposition here. Residents, particularly those near the border, persistently complain about the influx of mainland residents and economic issues caused by small-scale traders who abuse the border-crossing system.

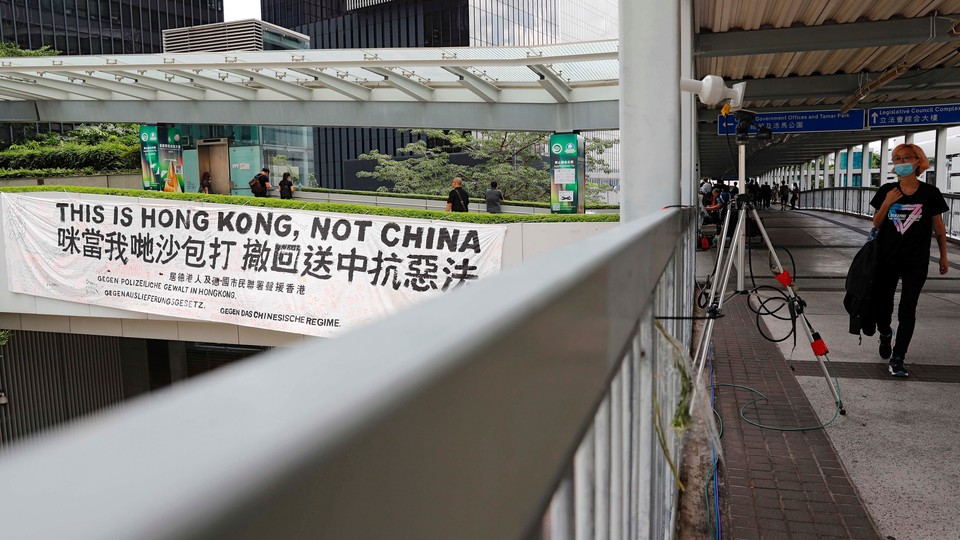

During recent protests, demonstrators have talked about their fears of Hong Kong disappearing, of it becoming just another mainland city. In June, when police fired tear gas at protesters, a now weekly occurrence that once seemed jarring, a foreign photographer was recorded yelling at police as they appeared to fire canisters at journalists. “It’s still Hong Kong, not China,” he bellowed. “Not yet.” In a movement devoid of public leadership, the moment briefly made him one of the faces of the rallies. His words—terse and livid—have been scrawled in graffiti and reprinted on posters since.

This openly expressed love of Hong Kong runs counter to the narrative of pro-establishment lawmakers here, as well as officials in Beijing and their nationalist supporters, who have painted protesters as a gang that is intent on tearing down Hong Kong. In this telling, the demonstrations have been an attempt at destruction backed by meddling foreign forces, particularly the United States and the United Kingdom. They often chide protesters for disrespecting the notion of one China or one country, an idea that Beijing has been working hard to cement in Hong Kong.

During a recent interview, Regina Ip, a pro-Beijing lawmaker in Hong Kong’s legislature who staunchly defended the extradition bill, broke off from our discussion to offer a clarification. The bill, she told me, had been wrongly termed by the media and the public. “We call it ‘rendition,’” she said, “because we are not a country.”