The Persistent Complexity of Tool

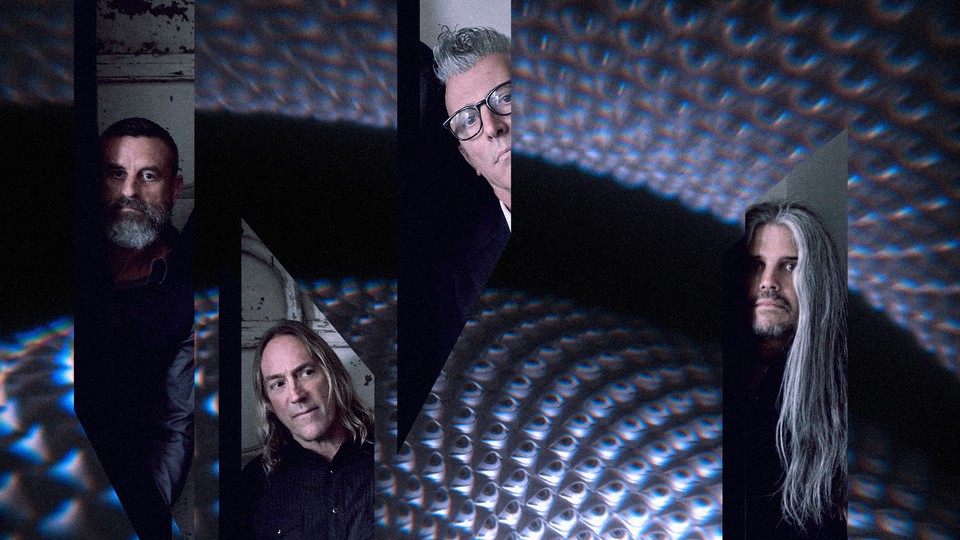

Back with new music after a 13-year hiatus, the legendary metal band is as precise and devastating as it has always been.

“To hear a Tool song for the first time,” said Henry James—last night, in my dream—“is an impossibility.” Phantasmal Master, I think I know what you mean. Tool music, with its long, magisterial patterns and ever-tightening curves, its helical risings and huge breakdowns, its floating grids of chug and its steppings-off into the sublime, its boring bits and its thrilling bits and its bits that sound like other bits, is not susceptible to instant appreciation. Once is not enough; with Tool music, once won’t work. The sources of its power are in ritual, repetition, restatement, rubbing your nose in it; in a complexity that becomes—on the 10th or 10,000th listen—incantatory.

So the odyssey I made earlier this week, from my home in Boston to the Sony office on Madison Avenue in New York, to hear the long-awaited new Tool album Fear Inoculum (debuting August 30), to hear it once, and then write about it, was in a sense preposterous. Fine with me: I love a preposterous odyssey. And yes, it was a privilege to be perched there among Manhattan’s sweating spires, in a boardroom with big speakers, listening—after 13 years!—to fresh Tool. To quote “Sweat”: “Seems like I’ve been here before / Seems so familiar / Seems like I’m slipping / Into a dream within a dream.” But I came out of the experience with almost no language. The five feverish pages of notes that I took are, it turns out, completely useless. Maybe not completely. “Winding intestinal solo ...” That’s not bad. “In the decay of a chord the tablas start up ...” That’s a decent observation. And I got some of the lyrics. As for the rest: gibberish.

For a Tool overview, you can’t do better than read my colleague Spencer Kornhaber. From Spencer you’ll get the vibe of early Tool, the allure of a grunge-era prog-punk-metal band, drowning in its own darkness and dickishness, that also seemed to have at least the beginnings of a program for transcending said darkness and dickishness. You’ll get a briefing on Tool’s esoterica, the mystical propellants of its music. You’ll get a line about the sound of Justin Chancellor’s bass upon which I cannot improve.

So I’m going to talk directly to the Tool fans, the ones who want to know: This new album, is it any good? Will it give me that Tool feeling? My answer is yes. Listening to it, I got a nearly unhandle-able amount of that Tool feeling. I teared up a couple of times, and when I closed my eyes there were purplish writhings across my brain space. You’ve heard “Fear Inoculum,” the single—musically a luxuriant, sinuous loop around the familiar sonic stations, lyrically a hymn to integration and deep breathing, with the vocalist Maynard James Keenan taking the part, for one verse, of a Satanic splitter/separator. “You belong to me / You don’t wanna breathe the light of the others / Fear the light / Fear the breath / Fear the others for eternity.”

These are Keenan’s themes, we’re toiling here under the same obsessional load, but there is a new emphasis (I think) on breath. The second track, “Pneuma,” is about, you know, the Holy Spirit, the wind that bloweth where it listeth, of which listeners are invited to partake with every inhalation. “This flesh, this guise, this mess, this dream … Wake up, remember / We are born of one breath / One word.” This is a monster song, a profound groove, the one I am most looking forward to hearing again. Adam Jones’s guitar is clipped, vicious, beautiful, and Chancellor produces those aqueous coils of reverbed bass, one after another, like a heavy metal John Martyn.

What else? Scattershot impressions. If you love the drummer, Danny Carey, you’ll love Fear Inoculum. He’s a huge presence, with his gongs and his tablas and his drum skins of varying tautness, unleashing octopoidal flurries that reformat the music in real time. Keenan’s voice is gentler—older—intact, still hovering and swerving, still making its folky dips and flutters, but with hardly a tight-chested scream on the whole album. The tracks are long: too long? Tool-long. I nodded off for half a second during the instrumental workout that is most of “Descending.” Or maybe I was entranced.

A ’70s sci-fi synth makes tasteful, whining, one-note appearances. There are battering Meshuggah-like compressions and long, soft ebbs of emotion. In my mind I saw not the illuminated neurology of Tool’s favorite artist, Alex Grey, but the flayed psychedelic carcasses of Hyman Bloom, almost explosive in their revealed energy. “A tempest must be true to its nature,” Keenan tells us in “7empest.” “A tempest must be just that.” What would be the point of a Tool album that didn’t sound, precisely and devastatingly, like a Tool album? We’ve been here before, to this dream within a dream.