/media/video/upload/georgetown-video_sjvt0Pi.mp4)

The Fine Line Campus Tour Guides Walk—Backwards

Guides are expected to serve as the face of the university and as an authentic voice for prospective students. Can they truly be both?

The clouds are playing matador defense on the sun when I get to the Washington, D.C., campus of Georgetown University in mid-July. They stunt at shading my already sweaty neck before retreating and allowing the sun to beat down once again. Walking into the Edward B. Bunn, S. J. Intercultural Center is a respite. There, seated and smiling behind a white pop-up table, I meet Jaydon Skinner—one of the university’s famous Blue and Gray tour guides.

In 40 minutes, Jaydon will lead a group of prospective students and their parents around campus. The group will bend around historic buildings, as Jaydon tells stories about the time he encountered former President Bill Clinton—“My tours have the presidential seal of approval,” he’ll say—and the school’s 2017 hire of a Hall of Fame NBA star and Georgetown alum, Patrick Ewing, as head basketball coach. But first, the nearly 200 people signed up for the tour will be crammed into a small, wood-paneled auditorium for an information session with Bruce Chamberlin, a senior admissions director at the university.

The group gathered here on this muggy Thursday is partaking in what, for some families, is a rite of passage: the summer college tour. No one would like to buy a home sight unseen, so why would families want to enter into a four-year-or-more deal with a sticker price of upwards of $200,000 without first seeing exactly what they were getting? Campus tours provide them with an opportunity to interact with students and admissions officers. They allow them to learn what exactly goes into the university’s admissions process. (Does the school require SAT subject tests? Personal essays? Do they do alumni interviews?) And at Georgetown, which seems to hit a new record-low acceptance rate each year, every iota of information could help.

Chamberlin, who himself was a tour guide while a student at Gettysburg College in Pennsylvania, gives a quick rundown of some hard truths about admissions. Pacing back and forth in front of the audience, he tells them that while he doesn’t “want to raise the anxiety,” he needs to paint an accurate picture of the process. The good news: If the students get in, they have a 98 to 99 percent chance of making it to sophomore year—and a 91 percent chance of graduating in four years. The bad news: The students cannot apply to the university using the Common Application, which is accepted by more than 800 colleges. More good news: The fact that Georgetown is not on the Common App means that the school’s application volume is not as large as it would be if it did use it.

Chamberlin gives the students a lot of dry, nuts-and-bolts information about the university: the history of the seal, the schools, how to declare a major. He talks about the university’s foundational values, which include “being a man or woman for others,” and urges students to examine who they want to be academically, intellectually, socially, and culturally. Of course, the narrative is a selective one, the school’s history evoked for its commitment to service and the liberal arts, pointedly leaving out the role of enslaved people in the school’s founding, despite the school having publicly wrestled with that part of its story in recent years. Diving into that is not Chamberlin’s job; he’s here to paint a portrait of a university any student would love to attend.

After about 35 minutes, Chamberlin wraps up and points to a slide with a photo of the city in autumn. He implores the crowd, “As you go on your tours, just picture this. A beautiful fall day, 72 degrees, and 50 percent humidity.” The group laughs. “Our tour guides can speak about the experience at Georgetown more authentically,” Chamberlin goes on. On top of that, they “are very good at finding shade trees, hydration stations, anything you need.”

The tour guides emerge, and Jaydon plays MC. “Hey guys, welcome to Georgetown, are you happy to be here today?” The tour guides introduce themselves inside the auditorium, then shuffle out of the room to the square outside where families divide themselves up based on who they want to lead their tour. Jaydon, a junior from Charleston, South Carolina, who is studying anthropology and political science, introduces himself first. Then there is Erica, the government major. Matt, the Aquarius. Emily, from Los Angeles.

The would-be Hoyas, their parents, and the guides head outside, and the heat has its way with us instantly. Prospective students make visors with their hands. Jaydon, coolly sporting a short-sleeved plaid button-up shirt, cutoff jean shorts, and white low-top Air Force 1s—the shoe of choice for most of the male guides—asks those who flock to him where they are visiting from. Richmond. Boston. New Jersey. California. North Carolina. China. He asks what they are interested in studying. “Oh, anthropology? Stick around after the tour, and we can chat about it,” he tells one student.

After the families choose their guides, and brief announcements are made—most significant, perhaps, that the university is close enough to Reagan National Airport that air traffic overhead will obscure some of the things he says—we’re off. Each group is its own flotilla in the fleet. Jaydon, stepping backwards over twigs, bricks, and sidewalk cracks, is our coxswain.

College tours are anxiety-inducing. For the students, for the parents, and for anyone who has ever watched someone walk backwards for an hour straight up staircases, around corners, and through buildings while spouting facts. That’s why, about a decade ago, several institutions moved to remake their campus tours. They told their tour guides to face forward and threw out their scripts. They paid tour consultants exorbitant fees. But here at Georgetown, the student tour guides still embrace the classic model. They stick to the script; they never turn away from the group.

The first plane buzzes overhead not long after the tour begins. The building to our left is White-Gravenor Hall. “If you look above the front door, there are two dates, 1634, and 1789. Those two dates have very important meaning in Georgetown’s history,” Jaydon says. Slowly marching. One, two. One, two. They are the dates that serve as markers of the university’s founding. Some historians say it was 1634, but 1789 is the date that the university, itself, recognizes. One parent moves her daughter toward the front. Jaydon never stumbles, but we do. The accidental bumps and sorrys and quiet my bads create a low hum as the group finds its rhythm behind Jaydon. The different guide-led groups fan out. One heads for the main gate. One group breaks left. Ours makes a beeline for Healy Hall—the main administrative building, and one of the most architecturally interesting buildings on campus. We pause.

“If you Google Georgetown, it’s probably the building that you’ll see,” Jaydon says. He gives a spiel about the president, the seminars he teaches, and the building’s library—which he swears looks like the library from Beauty and the Beast. We continue straight along the path in front of Healy Hall and past another library before we hang a right and go down a slight decline. Jaydon peeks behind himself and stops. A car is coming. He had tripped over one at an intersection the week before. “I’ve fallen a bunch of times, I’ve scraped up the back of my ankles,” he told me later. He usually tells people at the beginning of the tour, “Let me know if something is coming behind. It’s funny for you but not for me.” But it’s always safest to sneak a look occasionally.

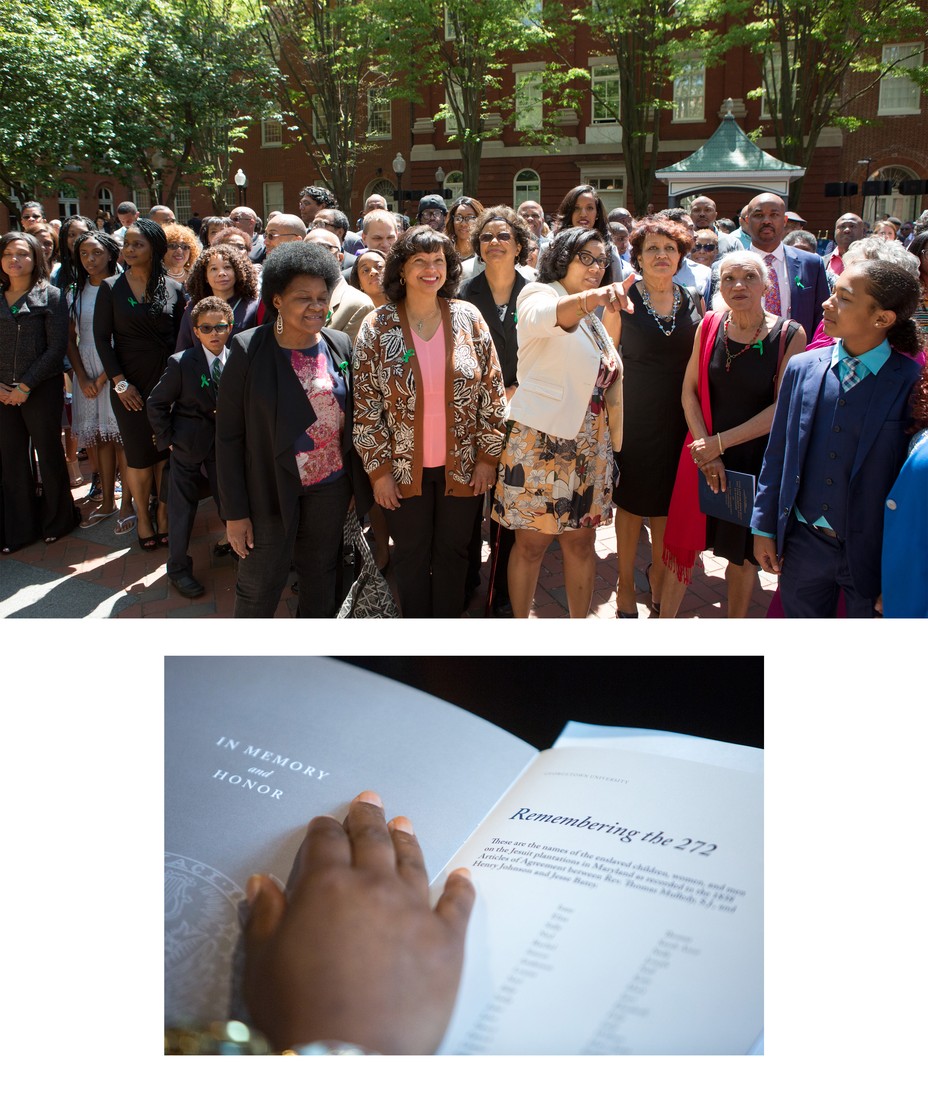

He steers us to the right, and I see a tree I know. Two years ago, in April 2017, this tree was watered by the descendants of the 272 people who had been sold to save the university. The “libations ritual,” as they called it, had been part of a day full of programming to acknowledge the university’s legacy of slavery. The tree stands in front of the sign for Isaac Hawkins Hall. Hawkins was the first enslaved person listed on the sale agreement in 1838. As some descendants watered the tree, others read all 272 names, one by one. William. Tom. Jim. Henry. Francis. Steven. Ann. Betsy. Matilda. Kitty. I’m pulled out of the memory by the footsteps of another tour group approaching us from behind. As the group nips at our heels, Jaydon simply explains that Hawkins Hall is one of the student residences. We move on.

A tour guide’s job is to present the university in the best possible light, and they train intensively to do so. Unlike at most colleges, the guides here at Georgetown are unpaid members of a student group. The group is, in part, how Jaydon—and other tour guides—found community at Georgetown, and that’s why many of them do it. When they join, they are given a handbook with information about the college, which they study as they join more experienced tour guides for training tours. Then they take an assisted tour, where another guide leads and they jump in occasionally, offering bits of interesting information. Then they host their own tour, accompanied by an experienced guide. Finally, they are on their own, walking backwards with a group of parents and students hoping to be in the 14 percent of applicants who will get to call themselves Hoyas.

Still, even though the guides are given a handbook, they can choose what to highlight and what to leave out. Each guide gives his or her groups something different. One might emphasize the dining areas they favor or buildings they have classes in; another might focus on campus programs and student life. And, of course, guides may mix things up day-to-day to keep the tours fresh for themselves.

The guides put a glossy sheen on the university, highlighting its best aspects and, at times, obscuring its flaws, pulling those who join them on their journey across campus into an expertly woven tapestry of fact, figure, and fun—with just the right amount of spin.

After tromping up hills and around bends, nearly everyone is wiping sweat away. Jaydon considerately lets us know we will soon be inside an air-conditioned building.

The building is the Leavey student center. Students bustle about, some high-school students here for summer programs, some Georgetown students taking summer classes.

Past the food court, Jaydon stops the group. This is the part where he tells his personal story. Neither of his parents went to college—in fact, no one in his family has. Still, the would-be first-generation college student knew that it was something he wanted to do—even though he didn’t know exactly what he was looking for in a college. He did know that he wanted to study political science, and doing it at one of the country’s top schools, located in the nation’s capital, seemed appealing. So he applied to Georgetown during the early-action period, which allowed him to learn his admissions decision by mid-December. He was not admitted during that period. He made other college plans. He picked out potential classes. He had his eyes set on another institution. But Georgetown was still working in the background. If a student doesn’t get in during the early-action phase, they are lumped in with the regular-decision applications and looked at again.

In April of his senior year, Jaydon received a small, thick envelope from Georgetown in the mail. He took it upstairs to open in his room. He got in. But he had never visited the campus. He had tried to visit several times, but the first few times, flooding in Charleston, where he’s from, meant that flights out of the city were canceled. Another time he came down with food poisoning.

He decided to attend Georgetown anyway, sight unseen. Move-in day was the first time he saw campus, and he was dropped off at the wrong gate. “I wouldn’t recommend anyone do that,” he says, and the group chuckles. By virtue of being on Jaydon’s tour, they are a little bit more informed than Jaydon himself had been as a prospective freshman. And in the hectic world of highly selective college admissions, that little bit could make all the difference.

Several students and parents huddle around Jaydon to ask questions after the tour, which ended after he shared his personal story. How many classes can students take in a subject before declaring a major? Where are the baseball coach’s offices? What are the requirements for the different undergraduate schools? The group dwindles to a few families who stand to the side Googling nearby lunch options, and Jaydon is nearing the bottom of his Smartwater.

If he had gone on a campus tour the summer before his freshman year, “I definitely would have known it got this hot,” Jaydon laughs. And if he’d had a tour guide like himself to talk to about his college decision, he might have known more about the resources for students on campus, meal plans, the dorms, the faculty. All of it. “Hearing from someone who is actually going to the school and wants to tell you about it definitely provides you a more candid look at the university—something you can’t get from a website or a video,” he says.

Jaydon might still have his guide face on as we’re talking. He doesn’t like to talk about what he doesn’t like about Georgetown. Sometimes on tours people ask him to, and when they do, he likes to talk about the things the university is doing to address its issues. “Obviously things that I don’t like about Georgetown are my own experiences and interactions and everyone’s are going to be different,” he told me. Though he also recognizes that, in many cases, the university is working to address those issues—even if not at the pace he would like it to. “I want to try to be as honest and straightforward as I can while still being a positive representative of the university.”

Campus tour guides are placed in a difficult position. They are mouthpieces for the university, but at the same time, prospective students look to them for an accurate depiction of college life. Walking that line is tough; even more so when you’re doing it backwards.