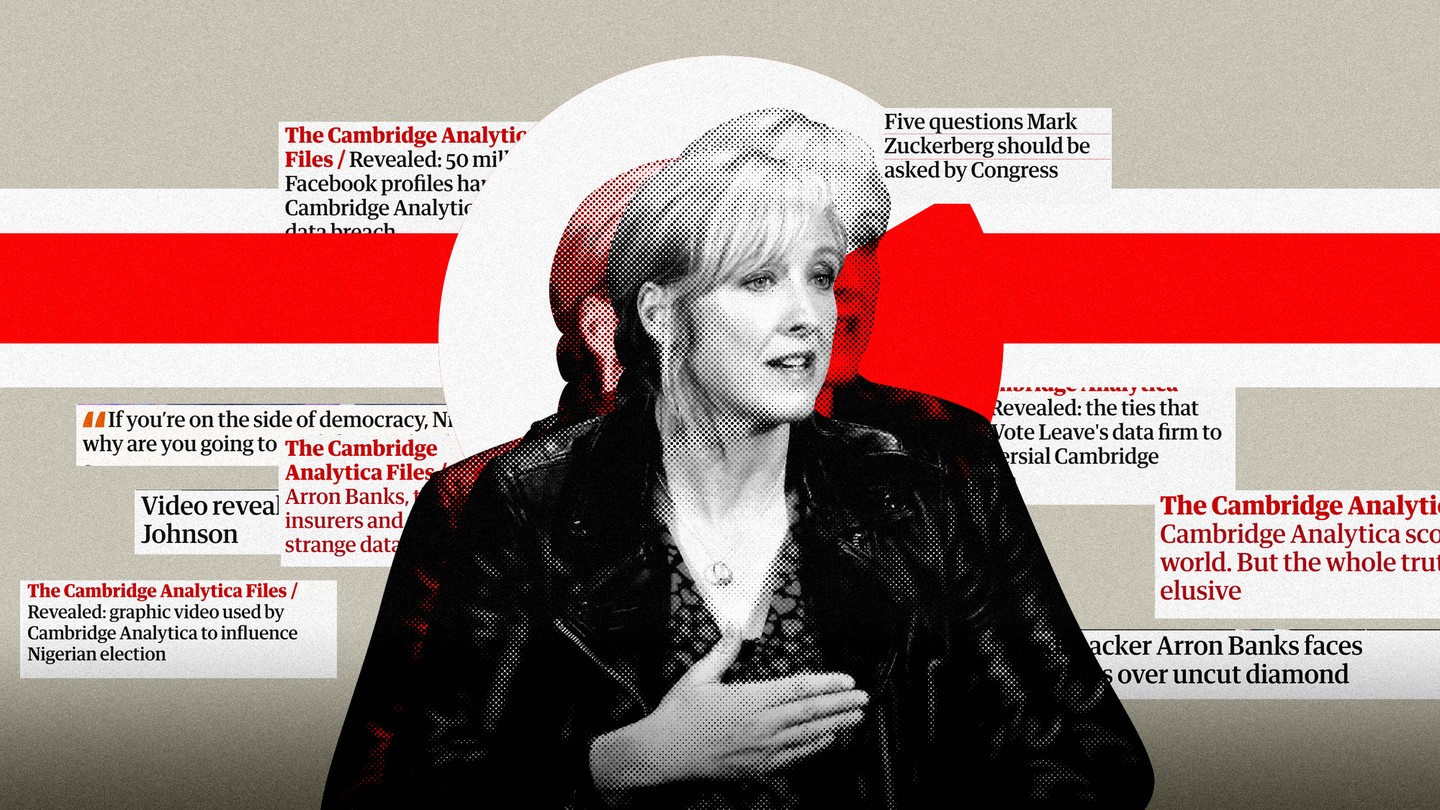

Britain’s Most Polarizing Journalist

Carole Cadwalladr is an icon to her supporters. But to her opponents, many of whom use sexist and ageist language to discredit her work, she is a conspiracy theorist.

Updated at 4:13 p.m. on November 5, 2019

LONDON—Carole Cadwalladr is different from the stereotypical British journalist. She is earnest where many are regarded as cynical. Fractious while others are chummy. An activist freelancer whose rivals inhabit berths with the big media players.

To her fans, Cadwalladr is an icon—a brave, irreverent, truth-seeking missile, exposing a nexus of corruption that is subverting our body politic, not only the Woodward and Bernstein of Brexit, but also its Emmeline Pankhurst, tirelessly campaigning for what she sees as a just outcome. But to her opponents, she is something else: a hysterical middle-aged conspiracy theorist, someone who pushed her stories beyond what the facts supported and who was willing to legally threaten journalists she was working with to get her way—or, in the words of the BBC journalist Andrew Neil, a “mad cat woman.”

She may also be among the most consequential reporters of her age, changing the way we talk about Facebook with her revelations of how Cambridge Analytica was mass-harvesting data to influence elections, and supercharging a movement for electoral reform with stories about illegalities at a pro-Brexit campaign group. Her articles have triggered investigations, were partly responsible for hauling Mark Zuckerberg in front of Congress, and helped result in Facebook being fined several billion dollars. They have also won her more than a dozen awards, and seen her named as a finalist for a Pulitzer. She is even the thinly veiled inspiration for the journalistic hero in a recently released young-adult novel.

Yet as her star has risen, so have her opponents. Operatives from Vote Leave, the pro-Brexit campaign group subject to her investigations, have gone from outsiders who managed to win the 2016 referendum to dominating Boris Johnson’s new British government. Dominic Cummings, Vote Leave’s former campaign director—who has accused Cadwalladr of spreading a “loony conspiracy theory”—is now one of the prime minister’s most influential advisers.

As Brexit spawns an American-style culture war in Britain, Cadwalladr has become a lightning rod. Her rise also reveals something about the state of British media, where social-media-powered campaigners can become megastars. How did she become the most polarizing reporter in Britain? Is Cadwalladr even a reporter, or more of a campaigner—an activist with policy goals she is pursuing through journalism? Does it matter?

To get to know Cadwalladr, I spent time with her in January, watching her at work, and have exchanged messages with her for months. Our initial meeting did not take me to The Guardian’s offices in central London, but to her Instagram-perfect apartment, full of flowers, white walls, and communist kitsch in a privatized apartment on a public-housing block a few minutes from some of the most genteel parts of North London. Sitting at her feet is Meg, her aging collie cross retriever. There is no cat.

Before she found herself on the trail that led to her fame, Cadwalladr and a friend were developing a script for a television show. The plot centered on women who, despite their lack of traditional academic qualifications, are recruited by Britain’s domestic intelligence service for their neglected skills and emotional intelligence. This is very much her vibe: an extremely funny, relentlessly sweary, exceedingly down-to-earth and highly unlikely candidate to be flung into a world of spies and disinformation.

When she began her investigation into Cambridge Analytica, Cadwalladr says, she did not even have a permanent pass to enter The Guardian’s headquarters. Though The Guardian has a large full-time staff based in London and elsewhere, it—like many other outlets, including The Atlantic—also employs freelance journalists and pays them for individual stories or projects. Complex, risky, and ultimately award-winning investigations into data harvesting by the United States’ National Security Agency and Cambridge Analytica were written entirely, or in large part, by freelancers.

The paper actually wrote about Cambridge Analytica before she did, but failed to capitalize on a 2015 scoop revealing the firm was harvesting Facebook data. In 2017, after publishing an article on the company’s ties to the American billionaire Robert Mercer, Cadwalladr began contacting former employees on LinkedIn. Eventually, she was introduced to Christopher Wylie, the pink-haired former staffer who would, over time, become famous for blowing the whistle on its practices, saying he felt a “huge amount of shame” about the data he weaponized in 2016. “He’s like Snowden,” Cadwalladr recalls telling her editors, referring to the contractor Edward Snowden, who leaked the NSA story, “but he’s like the gay, fun Snowden.”

When Cadwalladr presented her reporting to The Observer, The Guardian’s Sunday edition, she told me her editors said it would have to run as a short news story. Convinced it couldn’t be told in just a few hundred words, Cadwalladr walked out of the meeting, taking the story to the all-female team of feature editors at The Observer’s New Review, typically home to light Sunday reads. “I was like, ‘Okay, that’s it … The women are going to have to do this one,’” Cadwalladr joked. The article eventually came out a month later—appearing in both the New Review and, in shorter form, the news pages—after almost a year of work.

Throughout, Cadwalladr was talking and working with Wylie almost daily, a relationship that illustrates her journalistic style: She does not operate like a traditional reporter, favoring objectivity and distance; instead, she becomes close to her subjects, intensely—and, her critics would argue, unethically—so.

For Wylie to speak publicly, she helped find him legal representation, and in her telling, Wylie’s lawyers then pursued a financial backer to cover his legal fees in the event he was sued. She says she was not informed who the backer was, and did not mention the issue in her articles. According to Cadwalladr, The New York Times and Britain’s Channel 4 News, which were partnering in the investigation, were informed of the arrangement, and Wylie’s lawyers did due diligence to make sure the backer wasn’t “a Russian oligarch or something” and to avoid any other “conflict of interests.” (A Times spokesperson initially said that the paper was not aware of the financial-backer arrangement and that had Cadwalladr helped to arrange financial backing it “would violate our journalism guidelines, which cover outside contributors.” After the publication of this story the Times reviewed communications with Cadwalladr and found that, in late 2017, she had mentioned to the Times that another media outlet was considering an indemnity for Wylie. “However, The Times did not know that Mr. Wylie had later secured an unidentified financial backer to cover his potential legal costs,” the spokeswoman said. She declined to say whether this arrangement would violate the Times’s guidelines. Channel 4 News said it knew of, but could not independently identify, the backer. A spokesperson for Guardian News and Media, the parent company of The Guardian and The Observer, declined to comment, saying, “We are not going to go into confidential discussions between editorial colleagues.”)

Some might see Cadwalladr’s willingness to be involved—even indirectly—in financially helping a source as a violation of journalistic standards, one that left her (and her stories) vulnerable to questions about such a backer’s motives, but Cadwalladr believes that her close relationship with Wylie was essential to informing the public. “I can say with 100 percent certainty that an American journalist who treated their source with cool detachment and distance would never have gotten this story,” she says. “Wylie would never have trusted them, and the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica story would have gone unreported.” She says she found it “entirely reasonable” for Wylie to seek a financial backer because he “was taking a huge legal and financial risk” in coming forward, which required him to break a nondisclosure agreement. (Wylie did not respond to an interview request or a message that Cadwalladr says she sent him suggesting he speak with me for this article; his lawyer did not respond to a request for comment on the financial-backer arrangement.)

Because The Guardian did not employ Cadwalladr full-time, its ability to exercise control over her was limited, allowing her to blur the distinction between journalist and activist. Though the newspaper’s lawyers advised her not to, in advance of her article being published, she shared some of her reporting with an official British investigation into Cambridge Analytica after authorities approached her, and she put former employees in contact with them. (Representatives from Channel 4 News and The New York Times said they were not aware she had done this.)

Cadwalladr also relied heavily on storytelling, and lots of it—it took a veteran feature writer and author of a well-reviewed novel, rather than a classic investigative reporter, to make complicated stories about tech, data, and political funding go viral. Yet The Guardian’s presentation has been criticized by some journalists, including Michael Lewis, while a particular gripe among pro-Brexit critics was that Cadwalladr presented Wylie’s work at Cambridge Analytica as a devastating secret weapon that could swing elections for those who hired him, rather than expressing skepticism about his claims. Separately, Nick Clegg, the former British deputy prime minister who is now Facebook’s vice president of global affairs and communications, has dismissed claims that Cambridge Analytica influenced the Brexit referendum, suggesting “some kind of plot or conspiracy” was a simplistic crutch to explain away the result.

The particular approach Cadwalladr brought to her reporting was obvious to Shahmir Sanni, a former volunteer for Vote Leave. Sanni blew the whistle on the campaign’s significant overspending, which the Electoral Commission later found to be illegal. When Sanni realized irregularities were taking place, Wylie, whom he said he had met “in the gay scene” and who initially introduced him to Vote Leave, brought him into the fold with Cadwalladr. The journalist then turned him into a centerpiece profile and, as she’d done with Wylie, presented him as a heroic whistle-blower.

“She is an activist,” Sanni, who is still close with Cadwalladr, told me. “Of course, she’s a journalist whatever, but she’s both a journalist and an activist.”

The Cadwalladr I got to know was accumulating awards faster than many journalists accumulate bylines. But the baubles seemed hardly to have mattered. She appeared not only burned out, but also slightly traumatized by her own Twitter supernova. As we talked, she would often speculate about murky, hidden connections, which I struggled to unspool.

Cadwalladr is constantly relitigating her findings online, and fending off activist media outlets such as the pro-Brexit website Guido Fawkes, which has published stories attempting to discredit her work. Having suffered harassment and legal threats from some of the top pro-Brexit campaigners, Cadwalladr has come to believe that there is a “coordinated campaign” against her.

She sharply criticizes the BBC—Britain’s public broadcaster, which is still largely revered both here and abroad—as no longer being impartial and having engaged in a “cover-up” over the illegalities she has reported, and once took legal action against Channel 4 News, a former partner on her stories, accusing it of attempting to breach a publication agreement against her source’s wishes. She frequently knocks other outlets too—BuzzFeed News has published, in her words, “hit pieces” about her work and “spent months and months going after me.” (A BuzzFeed spokesperson said in a statement that the organization’s reporting “really speaks for itself” and noted that it included responses from Cadwalladr.)

What further singles out Cadwalladr’s crusade from the usual journalistic self-promotion, though, is that she has expressed a political objective: “a Mueller-style public inquiry” into Brexit. And she has been good at it, radicalizing those who support Britain’s staying in the EU; she has been lauded in Parliament, and several prominent lawmakers have joined in her call.

All the while—as she engages in debates online and goes after her critics—she receives a near-constant torrent of sexist abuse, which she showed me on her phone. One of the most extreme examples was a video of her being repeatedly hit in the head as the Russian national anthem played—a video posted to Twitter by Leave.EU, another pro-Brexit campaign group, run by the businessman Arron Banks. “Like my worst nightmare” was how she described the comments, “trying to shame me for not being married, for not having children, for being a middle-aged woman.” Many of the recurring Twitter attacks she mentioned to me appeared to be themed on the notorious barb from Neil, the BBC journalist: Trolls disparage her, commenting that it is “time to feed the cat” or “crazy cat lady kicking off again.” The BBC anchor, she says, has not apologized. Neil did not respond to requests for comment.

Paul Webster, the editor of The Observer, is quick to point out that British reporters have always been more adversarial and politicized than their American counterparts. “What is new is this is all taking place online,” he says. Great investigations might even play out this way in the future, he argues—a future where some journalists are celebrities, their work furiously promoted by online fandoms and denigrated by trolls. All this, he says, has made Cadwalladr “an extraordinary phenomenon.”

Cadwalladr, for her part, describes herself as “an activist for the truth,” telling me that it’s “not enough just to find out the truth, go through all the legal checks and balances and publish it. What I’ve discovered is that I’ve had to advocate for my journalism.”

What’s next for Cadwalladr?

The answer is bound up in that one word that has been making or breaking media reputations on both sides of the Atlantic: Russia. Cadwalladr’s campaign and online persona—but not her reporting—has leaned heavily on the notion of Russian involvement in Brexit. She has accused the leader of the Brexit Party, Nigel Farage, and Banks of accepting foreign funds, while highlighting a Vote Leave official’s contacts with “Kremlin-aligned groups.” (Farage has denied allegations that the Brexit Party received illegal foreign money.)

Her tweets have also bought into a lot of the imagery of the so-called Resistance media in the United States. Her occasional podcast, produced independently of The Guardian, is called “Dial M for Mueller.”

Both the governing Conservatives and opposition Labour Party here in Britain, she says, “have got reasons not to want to excavate problematic connections to Russia.” Why? She claims the Conservatives have taken money from “Russian oligarchs.” A spokesman for the party rejected the allegation, noting, “It is illegal in this country to accept foreign donations,” and adding that “donations to the party are properly and transparently declared to the electoral commission according to the law.” Cadwalladr, for her part, says this does not rule out wealthy Russian donors, such as Alexander Temerko, who have a history of ties to Russian intelligence and who are also British citizens.

She also claims that Seumas Milne, consigliere to the Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, has “pro-Putin views.” This, she tweeted, is influencing Labour’s ambivalent Brexit stance. The party’s greatest worry about seriously investigating alleged illegalities in the Brexit referendum, Cadwalladr argues, is that it might turn up proof and be forced to respond, alienating the pro-Brexit voters the party won over in recent years. The Labour Party did not respond to a request for comment, saying it never comments publicly about staff.

Cadwalladr’s claims have not gone unnoticed by fellow journalists: The connections, without clear evidence, on topics such as Brexit and the comments of Boris Johnson have made her arguably the most sarcastically subtweeted person on British political Twitter.

Where will all this end? Will Cadwalladr wind up like Glenn Greenwald, with a loyal following but a controversial alt-reporting platform? Or Seymour Hersh, a former star dented and dimmed after a series of questionable claims?

She has launched a crowdfunding account on Patreon, drawing on donations from supporters who pledge monthly amounts to back her work. At its peak in January, Cadwalladr had 411 donors who had collectively pledged $2,143 a month. As of yet, nothing has been posted on the site. Cadwalladr says she hopes to use these funds—as well as winnings from a €20,000 ($22,500) prize given to her by Sweden’s Stieg Larsson Foundation—to create her own website, called The Citizens, to lead “the online Twitter sleuths.” These are the anti-Brexit and anti-Trump activists she collaborates with, blending campaigning with citizen journalism and, she hopes, eventually connecting the dots between Donald Trump, Russia, and Brexit.

The arrival of Johnson and Cummings at Downing Street has sent her feuds and fundraising into overdrive. Cadwalladr’s reporting has put direct pressure on Cummings—in March, he was found in contempt of Parliament after refusing to appear before a committee investigating fake news, with an agenda largely set by Cadwalladr’s revelations. The new prime minister has, meanwhile, dismissed as “codswallop” a video she obtained showing Steve Bannon boasting of his ties to him.

In an April TED Talk, she accused Banks, of Leave.EU, of having a “covert relationship with the Russian government,” prompting him to send her legal notice. She has responded, accusing Banks of harassment and an attempt to silence her by tying her up in complex court proceedings. Reporters Without Borders and other supporters of press freedom have written to the government in her defense. To support her reporting and legal battle, she recently launched a new online fundraising drive, a GoFundMe, and at the time of this writing has raised nearly £300,000 (about $370,000). Andy Wigmore, a spokesman for Banks, did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

The legal action has strained Cadwalladr’s relationship with The Guardian, which she says declined to offer her financial support in her legal situation. Banks has sued her over comments she made in public talks—“both of which were about my Guardian investigation”—and a tweet. A Guardian News and Media spokesperson acknowledged that the company was not offering financial support, but said they were helping in other ways, including by working with press-freedom groups and by continuing to publish her articles. The colleagues who worked with Cadwalladr on the Cambridge Analytica story “have been enormously supportive” of her since the company’s decision, she says.

Although Cadwalladr was confident that she had “very sound defenses in truth and public interest,” she nevertheless worried that her case had wider implications. “My fear ... is that this will open the floodgates for similar attempts to silence other journalists,” she says.

For now, at the height of her fame, both her reputation and these court cases hang in the balance, having become bound up with whether claims of Russian involvement in Brexit and Trump’s election check out. In March, Vote Leave admitted to the wrongdoings brought forward by Sanni, though proof of direct funding and coordination between pro-Brexit campaigns and the Russian government has not materialized. Evidence has emerged across Europe of Russians seeking to influence right-wing politics, but in the United States and here, the picture remains less clear. Robert Mueller’s investigation into Trump fell short of alleging the president’s campaign engaged in a full-blown conspiracy with Russia. Cadwalladr argues the actions described in the Mueller report are devastating enough, even without evidence of a criminal conspiracy. And when it comes to Brexit, she told me, “for different reasons, Facebook and the government really, really, really don’t want the truth to come out, so that just makes me more convinced we have to get it.”

In October 2018, Britain’s National Crime Agency opened an investigation of Banks’s funds, which some thought could reveal whether money given in his name to pro-Brexit groups came from foreign sources. Cadwalladr felt confident enough in his alleged complicity to march with Sanni during an anti-Brexit protest to leave a placard emblazoned who bankrolls arron bankski? outside the National Crime Agency. (The NCA, which concluded its investigation following publication of this article, ultimately cleared Banks; a separate police investigation into Leave. EU’s funding had already been dropped).

If she is wrong, then both her “Brexit-Trump-Russia” narrative and her career will be in trouble. If she is right, she may have a place in journalism history and validate her reporting-campaigning style.

“They can’t just dismiss me as a conspiracy theorist anymore,” Cadwalladr told me. But no matter what she publishes, many people in the most powerful offices in London will be more than happy to do just that.

This story has been updated to reflect new information provided by a spokeswoman for The New York Times, and the results of a National Crime Agency investigation. It has also been updated to clarify that Cadwalladr accused Nigel Farage’s Brexit party of being willing to accept foreign funds. An earlier version of this piece said she accused the party of having received such funds.