It might be the most ironclad law of politics in 2019. Democrats win cities—period.

They win in big cities, like New York, and small cities, like Ames, Iowa; in old cities, like Boston, and new cities, like Las Vegas. They win in midwestern manufacturing cores and coastal tech hubs, in dense cities connected by subway and in sprawling metros held together by car and tar. If you Google-image-search a map of county-by-county U.S. election results, what you will see is a red nation dotted with archipelagos of urban blue.

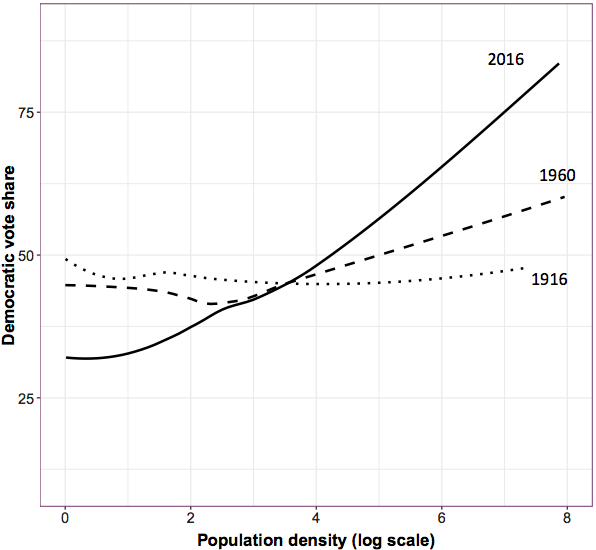

This fact may not seem worthy of inquiry, since the Democratic Party is the nation’s more progressive party, and—dating back to the Italian city-states of the Middle Ages—populous and diverse places have typically been more open to new ideas in science and politics. One hundred years ago, however, Democrats represented a wildly different constituency of rural white southerners and populist western farmers. In 1916, Woodrow Wilson’s support in America’s rural counties was, if anything, slightly higher than his support in urban counties.

So how did Democrats and density become synonymous?

According to Jonathan Rodden, a Stanford political-science professor and the author of the new book Why Cities Lose, the Democrats’ transformation into an urban party was not a smooth process so much as the result of several inflection points in the past 150 years.

The story begins in the late 19th century, in the filthy, sweaty maw of the Industrial Revolution. To reduce transportation costs, industrialists had built factories in cities with easy access to ports. These factories attracted workers by the thousands, who piled into nearby tenements. Their work was backbreaking—and so were their often-collapsing apartment buildings. When urban workers revolted against their exploitative and dangerous working conditions, they formed the beginning of an international labor movement that would eventually make cities the epicenter of leftist politics.

While workers’ parties won seats in parliamentary European countries with proportional representation, they struggled to gain power in the U.S. Why didn’t socialism take off in America? It’s the question that launched a thousand political-economy papers. One answer is that the U.S. political system is dominated by two parties competing in winner-take-all districts, making it almost impossible for third parties to break through at the national level. To gain power, the U.S. labor movement had to find a home in one of those parties.

This set up the first major inflection point. America’s socialists found welcoming accommodations in the political machines that sprouted up in the largest manufacturing hubs, such as Chicago, Boston, and New York. Not all of the “bosses” at the helm of these machines were Democrats; Philadelphia and Chicago were intermittently controlled by Republicans. But the nation’s most famous machine, New York’s Tammany Hall, was solidly Democratic. As that city’s urban manufacturing workforce exploded in the early 20th century, Tammany Hall bosses had little choice but to forge an alliance with the workers’ parties.

That led to a second inflection point, in the person of Al Smith. Manhattan-born, Irish Catholic, and a four-term governor of New York, Smith identified with immigrants and urban workers. When he won the 1928 Democratic presidential nomination, he arguably became the first urban national candidate, and won the support of blue-collar Catholic voters in cities across the country. Although he lost the election to Herbert Hoover, Smith’s candidacy marked a watershed in American history, as Rodden writes:

What started as an idiosyncratic local connection between urbanization and Democratic voting in New York quickly spread to the rest of the industrialized states in 1928 … [Smith’s platform] was not quite the agenda of the Socialists, but it was the beginning of the Democrats’ transformation into a party of the urban working class.

Smith’s successor as New York governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, had better political fortunes: He won a landslide presidential victory in 1932 after the economy crashed, and his New Deal incorporated several elements of the socialist agenda, including Social Security and unemployment insurance. But FDR’s victory did little to solidify Democrats’ standing in the city. Passing the New Deal required the cooperation of politicians representing the distressed rural South. An alliance between the interests of the white manufacturing working class and southern segregationists lasted for decades.

Miles away from New Deal negotiations in Washington, however, millions of black Americans were forcing the third inflection point as they moved from the rural South to cities, especially in the North and Midwest. During the Great Migration, from 1900 to 1960, the black percentage of the populations in South Carolina and Florida declined by more than 20 percent. In that same time period, the African American share of Detroit, Cleveland, and Chicago rose from less than 2 percent in each city to more than 20 percent of the population.

Black voters pushed urban Democrats in these northern cities to protect their labor and voting interests.

By the early 1960s, the Democratic Party was an unstable coalition, balancing the support of black urban workers with that of southern segregationists from whom they had fled. With the Civil Rights Act, signed by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964, Democrats effectively renounced their southern flank. Out of 20 southern Democratic senators, just one—Ralph Yarborough, of Texas—voted in favor of the bill. In 1968, Democrats won less than 10 percent of the once-dependable white southern vote while sweeping the urban manufacturing cores of the Northeast and the Midwest, from Worcester to Wichita.

Only in the past 20 years have dense counties in the South become reliably Democratic, Rodden writes. Since the 1990s, southern cities have become more similar to their northern kin, boasting a similar mix of large companies and explosive growth in college-educated adults. What’s more, the Great Migration has started to reverse itself. In the past few decades, with the deindustrialization of northern manufacturing towns, millions of black families have returned to metros in Texas, Georgia, and North Carolina, bringing their politics with them. Black families on the move have twice pushed Democrats toward becoming a party of the city—first in the North, and then in the South.

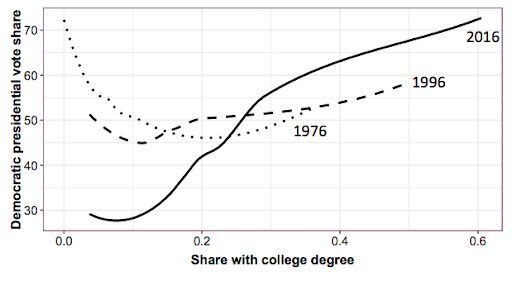

There is no obvious reason why a 19th-century movement led by Irish Catholic noneducated factory workers should become a 21st-century party for college grads, nonwhite voters, and software developers that defends gay rights, women’s rights, and legalized abortion. But it makes sense if you understand the Democratic Party through the lens of the modern city. Starting in the 1970s through today, Democrats and Republicans have been compelled to take sides on issues that hadn’t previously been politicized. And they have routinely sorted themselves along urban-rural lines, creating a pattern where there was once merely a tendency.

Take the issue of abortion, for example. Party identification didn’t use to work as a proxy for one’s opinion on reproductive rights. (In private conversations, the Republican President Richard Nixon even said, “There are times when an abortion is necessary.”) When the issue became part of the culture war after Roe v. Wade, however, Democrats embraced the viewpoint of the more secular city and consolidated their pro-choice position. So too, they sided against prayer in school and laws protecting “traditional” male-female marriage. Meanwhile, Republicans in the past 40 years have used socially conservative stances to strengthen their position with their more religious rural base.

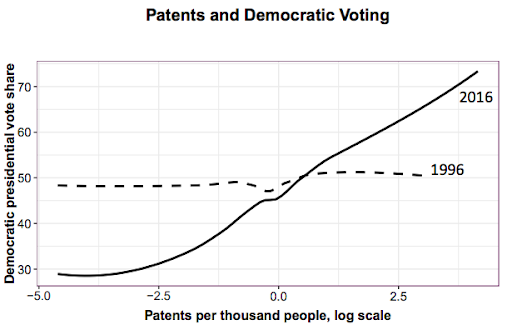

City demographics, if not quite city values, also explain how Democrats went from the party of hardware to the party of software. As low-skill factory work has moved out of the urban core, blue-collar urban workers have been replaced in city centers with immigrants and college graduates working in finance, tech, marketing, and media. This has made Democrats “advocates for the nascent globalized knowledge-economy sector,” Rodden writes. As recently as 1996, there was no relationship between a county’s likelihood to produce patents and its Democratic voting share. Today, Democrats win overwhelmingly in counties with the largest number of patents per 1,000 people, such as San Jose and Seattle.

With America’s biggest metros drawing millions of young educated workers, the urban-rural divide has also become a diploma divide. Throughout the 1980s, college graduates were as likely to vote for one party as the other. But by 2016, Democrats had become the party of nerds. Meanwhile, Donald Trump won the Republican nomination while proclaiming in the midst of the primary, “I love the poorly educated!”

Psychological factors reinforce the phenomenon of the liberal Democratic city. In his 2008 book, The Big Sort, Bill Bishop argued that Americans were self-segregating by neighborhood, creating balkanized urban areas of kale-munching libs who find Cracker Barrel America culturally incomprehensible. Evidence for Bishop’s thesis is uneven, but there might something to the idea that blue cities get bluer due to sorting effects. As the writer and researcher Will Wilkinson argues, cities are magnets for individuals who score highly on “openness”—the Big Five personality trait that comprises curiosity, love of diversity, and open-mindedness. He points to research showing remarkable concentration of self-described “open” personalities in urban centers around the world, such as London.

It’s also conceivable that living in a city might naturally promote ideologies that correspond with the modern Democratic Party. The modern city brings its residents into constant interaction with the fact of, and necessity for, state intervention. Urban residents trade cars for public transit, live in neighborhoods with local trash codes, and deal with planning commissions about shadows, ocean views, and parking rights. City residents are natural “externality pessimists,” to use Steve Randy Waldman’s clever phrase, who are exquisitely sensitive to the consequences of individual behavior in a dense place where one man’s action is another man’s nuisance. As a result, residents of dense cities tend to reject libertarianism as unacceptable chaos and instead agitate for wiser governance related to health care, housing policy, and climate change.

The near future of migration will put some of these theories to the test. In the past few years, young adults have been leaving the richest, densest metropolitan areas and moving south and west—to the suburbs of Austin, and Raleigh, and Vegas, and Phoenix. They’re not looking to start a political movement. They’re just looking for affordable houses, good schools, and good jobs. Their urban exodus is moving them into Republican regions, blurring the clean divide between the deep-blue city and the ruby-red countryside.

This is the epilogue of our 150-year saga. What happens when the liberal city distributes itself throughout the suburbs of the South and the West? If the blue city of the Northeast changed American politics, will the blue suburb of the Southwest do the same?