Donald Trump Knows How to End Homelessness

As a real-estate developer, he repeatedly argued that building adequate housing requires federal subsidies. As president, he’s forgotten that.

Donald Trump has long understood that he can leverage homelessness to motivate people. In the early 1980s, the developer was desperate to get tenants out of a building he owned in Manhattan so that he could tear it down and build a new one. The tenants were not obliging, so Trump tried a series of moves to force them to vacate—including offering to house homeless New Yorkers in the building, hoping revulsion would scare the tenants out.

Now, as president, Trump is once again turning to the fear of the homeless as a tool. The administration has begun threatening some sort of major action on homelessness, likely in California. It’s not clear what actions the administration might pursue, nor how federal authority would interact with local government. One reported idea is to demolish Los Angeles’s famed Skid Row. A report from the White House Council of Economic Advisers on Monday focused on the use of policing, apparently a gesture at the idea of rounding homeless people up.

Trump again called for action on Tuesday, during a visit to California.

“We have people living in our ... best highways, our best streets, our best entrances to buildings and pay tremendous taxes, where people in those buildings pay tremendous taxes, where they went to those locations because of the prestige,” Trump told reporters. He also complained that foreigners who have moved to the U.S. for its prestige are upset about the problem.

While this looks mostly like a cynical ploy to embarrass Democrats in major cities, it’s also true that homelessness is a large and growing problem. Trump, the former builder, has been clear in the past about what’s needed to solve that problem: more affordable housing. Moreover, he argued that the federal government had an important role to play in expanding the housing stock through economic incentives. Yet now, with the power of the federal government in his hands, Trump is pushing an idea that would do little to solve homelessness.

Homelessness really is on the rise in the United States. The number of American homeless people rose in 2018, the second year in a row, with particular spikes in major cities like New York and Los Angeles. Unlike many thorny policy questions, this one is relatively straightforward. No policy solution will remove everyone from the streets, but policy experts and advocates agree that the leading cause of homelessness is that people can’t afford homes. Housing prices, especially in cities, are on the rise, and the supply of housing isn’t rising fast enough—which of course just makes the prices higher.

Because of its extensive resources and national reach, the federal government is best positioned to deal with this. But federal efforts are split between a variety of agencies, and have often focused on efforts like Section 8 vouchers that allow tenants to rent on the open market, with a subsidy. That has proved effective for getting recipients housing, but it doesn’t usually produce large new stocks of housing.

The government can expand housing stock in two ways. First, it can build public housing, though American public opinion has largely turned against such developments. Second, it can incentivize private developers to build affordable housing. Here’s how one expert described the need:

You can’t, Tom, build low-cost housing at a profit and I wish you could. You can build it efficiently and economically as long as you have assistance and help from the government. And I wish we could get that help from the government because it’s desperately needed. When you look at the homeless, when you look at all the problems on the streets, a lot of that is directly related to a lack of housing.

That expert was Donald Trump, appearing on Crossfire in 1987. Trump spoke in some depth on the topic, and his argument is fascinating.

“If you look at the homeless situation all over the country, it’s because of the fact that there is no housing,” Trump said, agreeing with the expert consensus. “The federal government used to have programs, a lot of programs; they don’t have any programs right now.”

Trump’s foil on the show was Pat Buchanan, the white-identity politician who is commonly portrayed as a harbinger of Trumpism. But on Crossfire, they did not agree. Buchanan pushed back on Trump, saying such programs already existed.

“Well, you know how small the programs are,” Trump replied. “I mean, if you look at the 1960s and the early ’70s, you have massive programs for low-, moderate-, and middle-income housing. Today you have virtually no programs. You have some minor program to senior-citizen housing … It’s just not enough.”

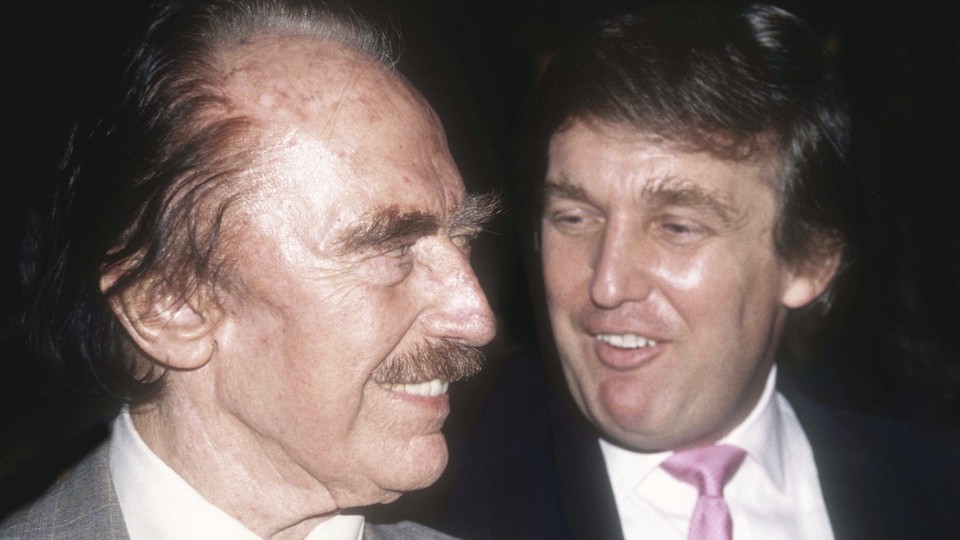

Trump knew well the power of such programs because his own family dynasty was a testament to them. Not as tenants, of course—instead, reaping federal subsidies was integral to Fred Trump’s rise as a developer. As Peter Dreier and Alex Schwartz wrote in The American Prospect in 2017:

The senior Trump made his fortune by building middle-class housing financed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). In the 1930s, Fred Trump built single-family homes for middle class families in Queens and Brooklyn, using mortgage subsidies from the newly created FHA in order to obtain construction loans. After his real-estate business fell on hard times, he revived his firm during World War II by constructing FHA-backed housing for U.S. naval personnel near major shipyards along the East Coast. After the war, he continued to rely on FHA financing to construct apartment buildings in New York’s outer boroughs.

This was not philanthropy. Fred Trump’s goals were to get rich, return to wealth, and get richer. Moreover, his company’s apparent racist discrimination in selecting renters was observed by everyone from Woody Guthrie, in 1954, to the U.S. Department of Justice, which sued the Trump Organization for discrimination two decades later, before settling the case. (These practices were not unique. The FHA’s policies were in general organized to enforce white supremacy.) But just because Fred Trump’s motives were self-interested doesn’t invalidate the benefit of building all that housing. That’s the point of federal subsidies: They effectively bribe people to do things that are publicly beneficial.

Trump has often tried to run the presidency as though it was a real-estate firm, with poor results. But this is one case where his business experience really is relevant, yet he’s discarded it. Three decades ago, Trump understood how the federal government could help with affordable housing, but as president, he seems to have forgotten. Even as he rails against homelessness, his administration has cut a range of housing-assistance programs. Now Trump is proposing a roundup of homeless people that would appear to do nothing to alleviate the housing crisis that precipitates homelessness.

The Council of Economic Advisers report on homelessness released Monday does not mention the Federal Housing Administration, nor does it mention subsidies to builders. In fact, it concludes that overregulation of housing, rather than a lack of federal involvement, accounts for scarcity. Trump signed an executive order aimed at cutting regulations in June, but housing advocates told my Citylab colleague Sarah Holder that they feared it would actually deepen the problem.

In any case, the CEA’s focus on cutting red tape pushes the issue back to the private sector. Back in 1987, Trump bristled at the idea that businessmen like him should deal with homelessness.

“Elected officials have that responsibility,” he told Playboy. “I would hate to think that people blame me for the problems of the world. Yet people come to me and say, ‘Why do you allow homelessness in the cities?’ as if I control the situation. I am not somebody seeking office.”

Now that he’s not only someone seeking office, but the holder of the most powerful office in the nation, though, he’s opted to duck the responsibility anyway.