This Land Was Our Land

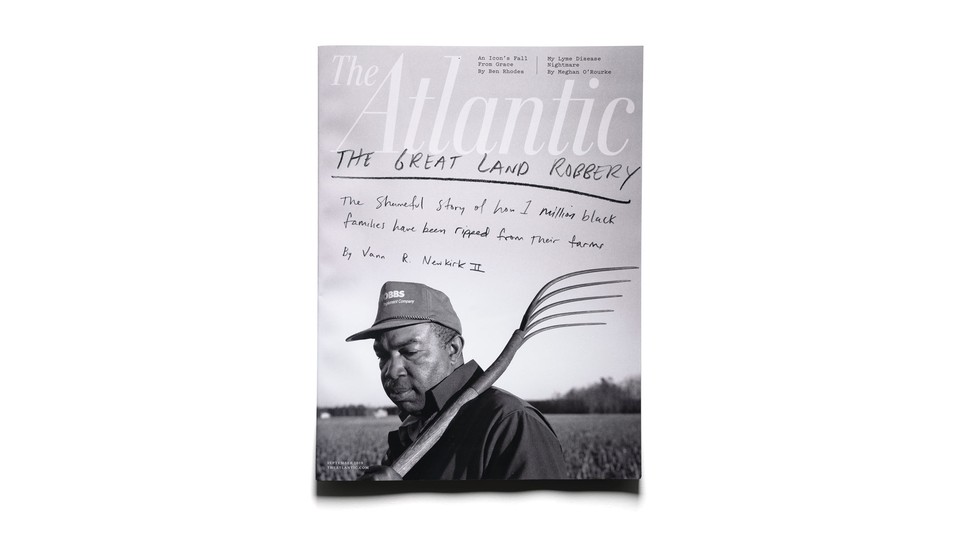

For the September cover story, Vann R. Newkirk II wrote about how nearly 1 million black farmers were robbed of their livelihood.

Mr. Newkirk’s poignant story about the precipitous loss of African American land sheds light on an issue that has affected—and devastated—generations of families throughout the South. The loss of this land, also called “heirs’ property,” has denied these families the most valuable and stable source of generational wealth.

However, we feel it is important to also illuminate the recent progress that has been made at the national level to address this issue. Together, we have led a bipartisan effort in the U.S. Senate over the past year to begin resolving the challenging bureaucratic and legal issues that have long plagued those Americans who have inherited land without a clear title. The 2018 Farm Bill included our legislation to make it easier for these landowners to receive a Department of Agriculture farm number—a crucial designation that unlocks federal resources. That bill also required a study of other issues that may be affecting the ability of heirs’-property owners to successfully operate farms and ranches.

Our home states of Alabama and South Carolina are widely considered ground zero for this issue. We’ve taken a good first step, but we have a lot more work to do to reverse this disturbing trend and protect this important foundation of black wealth in the South.

Senator Doug Jones of Alabama

Senator Tim Scott of South Carolina

Both the poignant cover photo, of a black farmer, and the powerful and beautifully written article by Vann R. Newkirk II reminded me of Edwin Markham’s famous 1898 poem, “

The Man With the Hoe.”

As Markham asks, “O masters, lords and rulers in all lands / How will the Future reckon with this Man?” And how will America reckon with 400 years of injustices and indignities visited on our black citizens and repair the damage? As a nation, we must consider some form of reparations if we are to right a profound wrong.

Benjamin J. Hubbard

Costa Mesa, Calif.

Vann R. Newkirk II replies:

Senators Jones and Scott: I thank you both for reading the story, and I know many of the farmers I spoke with would thank you for your interest in this policy issue. Several of the advocates I talked with focused on heirs’ property as one of the major ongoing mechanisms of black land loss, and I have watched as efforts such as the 2018 Farm Bill and your legislation have become some of the first meaningful federal actions against this aspect of dispossession in decades.

Those efforts can provide relief for the thousands of black families facing this type of land loss. I would note that my focus in the cover story is not necessarily heirs’ property on its own, but a wider epidemic of discrimination, illegal economic pressures, and disparate federal funding affecting black farm families—even including those with clear, established titles to land. I would also stress that this pattern of federally funded discrimination over generations dovetails with the heirs’-property problem to strip black families of wealth even before they officially lose the title to land, and that in many cases losses due to heirs’-property claims are the end of long chains of hardship. Severing those chains of hardship is a task that will require hitherto unseen policy efforts to repair past hurts and their effects in the present. I think the forthcoming USDA study can be useful, as will additional reporting on and testimony from black landowners and their scions.

Thank you to Benjamin J. Hubbard for your kind note. I am glad you mention Edwin Markham’s poem, as it came to my own mind often while I worked on this article and immersed myself for much of the past year in the stories of farmers and sharecroppers. Of the history of “immemorial infamies, perfidious wrongs, [and] immedicable woes” that have built the present, the story I document is but one, and I am grateful to have been able to tell it. I have a feeling that “The Man With the Hoe” will only grow in relevance as we truly grapple with our legacies of white supremacy, colonialism, and capitalism.

Meritocracy’s Miserable Winners

The system that’s widened the gap between the rich and everyone else has also turned elite life into an endless, terrible competition, Daniel Markovits argued in September.

I found your article on the price of meritocracy to be at once timely and painful. My shortcomings in the college-admissions process haunt me, and I feel like the consequences of my failure will reverberate throughout the rest of my career. I constantly feel deficient in merit.

I know that there are far worse things in this life than having failed to get into your dream college. I have never gone hungry. I grew up with two loving parents in a supportive environment with plenty of opportunities. We had more than enough money. In the end, I think it’s the fact that I grew up with so much privilege that makes me all the more angry at myself for having not gotten into a better school and thereby having not earned a better job. The runway was always clear, but I botched the takeoff. As you referenced in your article, so many folks do not have the game rigged in their favor like I did.

I know that reality often falls short of expectations, but nonetheless I have continually struggled to shake off the disappointment of a future lost. I am not asking for your pity, because, as you rightly point out, the rich of this country do not deserve any tears. I just want you to know that I am miserable too.

Connor Holbert

Chicago, Ill.

Daniel Markovits does an excellent job of describing the effects of “meritocracy” in our society, yet misses the single most important root cause.

Nearly a century ago, hourly workers won a universal 40-hour workweek. Salaried workers are, however, free to be exploited. Over the past three or four decades, we’ve watched worker productivity grow, along with salaried employees’ number of work hours, which in some cases completely subsume their lives. Getting ahead in the salary pool of a large employer means out-working your colleagues, which invariably involves trying to put in more hours.

Employers have reduced their employment costs by encouraging (directly or indirectly) their workers to do more than one person’s worth of work. Employees aren’t a bottomless source of corporate wealth, however. Efficiency falls after a certain number of work hours in a day. Decisions may not be as sharp; flaws can creep in. And companies can lose institutional knowledge when workers leave.

I submit that limiting the hours for all workers would do more to achieve the democratization of not only the workplace, but universities as well. Capping “worker productivity” in this way would force firms to hire more staff in order to fully exploit their markets. More jobs equals more opportunity, and the rest will sort itself out.

Perhaps we have to eliminate “salary” as an employment concept in the U.S. entirely and translate all wages into hourly pay, and mandate overtime for exceeding the 40-hour workweek, the only exceptions being for those in the C-suite and board members.

As an aside, I’m pretty certain that one of the drivers of companies pushing their salaried workers to do double duty has been the costs of “perks,” chief among them health insurance. Some sort of national effort to control that cost—or, better yet, to decouple it from employment—would erase or at least ease that burden.

Paul Flint

Brooklyn, N.Y.

As a libertarian it pains me to say this, but the only way to soften the meritocracy trap without destroying our economy is to enact a graduated income tax with much higher upper levels. If the federal income tax was, say, 50 percent on incomes greater than $200,000, and 90 percent on incomes greater than $500,000, no one would earn more than $500,000—only a fool would be willing to pay Uncle Sam 90 percent of their hard-earned income. The result, as in days gone by, would be that people would no longer be willing to work such long hours, opening up more opportunities for people who did not attend elite schools. There would be consequences for such actions. But more happiness would result.

Lloyd Wright

Poughkeepsie, N.Y.

In his excellent article, Daniel Markovits recommends the New Deal as a democratic model for undoing the deleterious effects of economic inequality with these words: “The broadly shared prosperity that this regime established came, mostly, from an economy and a labor market that promoted economic equality over hierarchy—by dramatically expanding access to education, as under the GI Bill, and then placing mid-skilled, middle-class workers at the center of production.”

Yet, as described in detail in Ira Katznelson’s When Affirmative Action Was White, the GI Bill was designed to systematically deny African Americans its benefits, with tragic results for millions of Americans and for our society as a whole. If there is another New Deal, it must be applied universally to avoid pernicious consequences.

Philip Siller

New York, N.Y.

Daniel Markovits originally and persuasively argues for wealth redistribution by appealing to elites’ sanity.

Is there a historical instance of the wealthy voluntarily forsaking their perceived immediate self-interest? In my overview of history, socioeconomic reform is a direct result of bottom-up social movements, not top-down political reform.

Myles J. Brawer

New York, N.Y.

Daniel Markovits is insightful and timely when he decries systemic meritocracy in our society. But the insight stops when he proposes a solution that comes out of the same meritocratic mind-set. Since the meritocratic playing field is miserable, the solution can’t simply be increasing the misery by opening it up to more players. Instead we need to counteract the view that educational and professional and economic “merit” are markers of human legitimization. On a deeper level, this can be done by recognizing the innately invaluable nature of every person regardless of achievement or the apparent lack of it. Practically speaking, this would involve giving the same societal value to people who aren’t considered educated or professional or wealthy as to people who apparently are.

Ted Barham

Dearborn, Mich.

Life With Lyme

After years of being ill, Meghan O’Rourke wrote in September, she found herself with one of medicine’s most bitterly contested diagnoses—a baffling disease that has pitted experts against one another and against patients.

I began reading Meghan O’Rourke’s article with some trepidation. As an internist, I am familiar with the controversies she describes. I have struggled with how to approach the dichotomy between the “science” and the symptoms, and have encountered many patients who are frustrated and angry, and think they know more than I do on this topic. In today’s health-care environment, where appointments are 15 minutes long for a medical history that could take an hour, there is a vicious circle of distrust and despair between doctors and patients. Ms. O’Rourke did a superb job of telling the story of Lyme disease in a way that was sensitive to the perspectives of both patients and physicians. Though it was personal and anecdotal, which is contrary to the evidence-and-epidemiology approach of the medical profession, it was very well researched, thoughtful, and evenhanded.

Aparna K. Miano, M.D.

Washington, D.C.

Meghan O’Rourke replies:

It’s interesting to hear a doctor talk about the challenges of treating frustrated patients. This letter captures something simple but very important about why Lyme disease and other complex, multisystemic illnesses (including some autoimmune diseases) are so challenging for the medical system: They are hard to diagnose accurately given the tools we currently have, and it’s hard to give suffering patients the attention their condition deserves when most appointments last less than 15 minutes. This has consequences beyond making patients unhappy. A lot of evidence shows that the experience of illness actually affects patients’ response to treatment. (Studies suggest, for example, that diabetes patients with “empathetic” doctors do much better than patients with nonempathetic doctors.) Since my article came out, I’ve heard from hundreds of suffering, and often despairing, people who felt driven away by the medical system. Meanwhile, doctors are experiencing extraordinary rates of burnout. Clearly we need more science around tick-borne illness, but we also need a system that gives doctors the time and support necessary to treat the entire range of complex illnesses that still exist at the edge of medical understanding.

Why Are Washing Machines Learning to Play the Harp?

Appliance makers believe more and better chimes, alerts, and jingles make for happier customers, Laura Bliss wrote in September. Are they right?

I read with growing horror the story about appliance manufacturers’ drive to invade my house with appalling jingles they think are soothing. The jingles are not soothing. They are extremely annoying.

Bryan Gangwere

Flower Mound, Texas

I have been wondering who designed the new sounds that seem calculated to make Chase Bank ATMs sound confiding and lovable. On the one hand, they’re a refreshing change from the shrill, tinny, and irritating electronic bleeps emitted by most ATMs and card-swipe portals. On the other hand, the fact that they get to me makes me feel wary and manipulated. How can I regard a bank as endearing?

Annie Gottlieb

New York, N.Y.

Laura Bliss replies:

Few readers seemed to wholeheartedly appreciate the musical tones emanating from machines in their daily lives, although I did hear a fair amount of the ambivalence that Annie Gottlieb describes.

Relatedly, I was pointed to a blog post by Robin James, a philosophy professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, theorizing that household appliances’ friendly but insistent jingles impelling us to keep working stem from the ugly gender politics of domestic labor. James writes: “Re-coding the bad feelings we have about oppression into good feelings about brands, these jaunty melodies take on yet another dimension of reproductive labor we disproportionately shove off on women, especially women of color.” So, yeah, not everyone’s singing their praises.