The Common Misconception About ‘High Crimes and Misdemeanors’

The constitutional standard for impeachment is different from what’s at play in a regular criminal trial.

“High crimes and misdemeanors” is surely the most troublesome, misleading phrase in the U.S. Constitution. Taken at face value, the words seem to say that impeachable conduct is limited to “crimes”—offenses defined by criminal statutes and punishable in criminal courts. That impression is reinforced by the fact that the phrase follows the obviously criminal “treason” and “bribery” in Article II’s list of the kinds of conduct for which the “President, Vice President and all civil officers” may be impeached.

But this is not, in fact, what the Constitution requires. “High crimes and misdemeanors” is not, and has never been, limited to indictable criminality. Nonetheless, despite centuries of learning on the point, there the phrase sits, begging to be taken at its delusory face value.

Accordingly, in nearly every significant American impeachment since 1788, the defenders of the impeached official—whether president, judge, senator, or Cabinet officer—have argued that their man can’t properly be removed, because what he did wasn’t actually a statutory crime. This process has already begun for President Donald Trump. Among the first things the president’s personal lawyer Jay Sekulow said in a September 27, 2019, CBS interview about the Ukraine affair was that the phone call between Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky involved “no violation of law, rule, regulation, or statute.”

Even some of Trump’s critics entertain the same erroneous notion. The New York Times columnist Bret Stephens has repeatedly intimated that, to him, “high crimes and misdemeanors” requires ordinary criminality. He recently wrote, “I struggle to see exactly what criminal statute Trump violated with the [Ukraine] call.”

Those most eager to impeach this president may know their Constitution better, but they recognize that crimes are just easier to explain than old Anglo-American legal jargon. So some are tempted to scour the criminal code for a subsection into which one or the other of Trump’s misadventures can be wedged. The most recent example is the vociferous but ultimately pointless argument over whether opposition research—dirt—on a political opponent is a “thing of value” for purposes of federal election laws.

There are two strong arguments against the idea that the phrase requires criminal behavior: a historical one and a practical one. The history of the phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors” and of how it entered our Constitution establishes beyond serious dispute that it extends far beyond mere criminal conduct. The practical reasoning is in some ways more important: A standard that permitted the removal of presidents only for indictable crimes would leave the nation defenseless against the most dangerous kinds of presidential behavior.

Let’s start with the history. The British Parliament invented impeachment in 1376, primarily as a legislative counterweight against royal abuses of power. Parliament couldn’t impeach kings and queens, and couldn’t get rid of them at all without an inconvenient and probably bloody revolution. So on occasions when the nobility wasn’t willing to strap on the old chain mail and gather its trusty men-at-arms to have a go at the king’s head, Parliament—acting on the maxim “Personnel is policy”—struck at the Crown by removing the monarch’s most powerful ministers through impeachment or, sometimes, bills of attainder.

Great Britain has never had a written constitution. And Parliament has never sat down to write an impeachment statute with a neat definition of the behavior that could get a royal minister impeached. Rather, Parliament has carefully kept impeachment open-ended, recognizing that one never knew in advance what form the royal urge to autocracy might take or what sort of devilry corrupt or ambitious officials might be up to. Over the centuries, Parliament impeached a good many people for a wide variety of misconduct. When it did, the articles of impeachment tended to describe the defendant’s behavior as “high crimes and misdemeanors,” a usage that dates back to 1386. Critically, a great deal of the misconduct Parliament deemed impeachable wasn’t criminal at all, at least in the sense of violating any preexisting criminal statute or constituting any judge-created common-law crime.

I could provide examples in eye-glazing antiquarian detail. Suffice it to say that Parliament has impeached high officials for military mismanagement (Lord Latimer, 1376; the Earl of Suffolk, 1386; the Duke of Buckingham, 1626; and the Earl of Strafford, 1640), neglect of duty or sheer ineptitude (Attorney General Henry Yelverton; Lord Treasurer Middlesex, 1624; the Earl of Clarendon, 1667; Lord Danby, 1678; and Edward Seymour, treasurer of the Navy, 1680), and giving the sovereign bad advice, especially about foreign affairs (William de la Pole, 1450; Lords Oxford, Bolingbroke, and Strafford, 1715).

Parliament has also impeached a good many officers for abuse of power, sometimes criminal, but oftentimes not. When the Constitutional Convention convened in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, the English-speaking world was riveted by the commencement of impeachment proceedings against Warren Hastings, governor general of Bengal, on just such grounds. Few if any of the charges against Hastings were indictable crimes, but that was immaterial to Edmund Burke, the principal parliamentary prosecutor of Hastings. He said the charges “were crimes, not against forms, but against those eternal laws of justice, which are our rule and our birthright: his offenses are not in formal, technical language, but in reality, in substance and effect, High Crimes and High Misdemeanors.”

Americans of the founding generation were familiar with the phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors” not merely because they were close students of the parliamentary history of the mother country, but also because both the American colonies and the early state governments had conducted impeachments of their own. For example, in 1774, just before the American Revolution, the Massachusetts colonial assembly impeached Chief Justice Peter Oliver for “certain High Crimes and Misdemeanors.” His offense? The decidedly noncriminal act of agreeing to accept a royal salary rather than the stipend appropriated by the Massachusetts legislature. The Oliver impeachment was a cause célèbre in both England and the colonies. John Adams is often credited with the idea of impeaching the judge. Among those voting to impeach Oliver were Sam Adams and John Hancock, as well as Nathaniel Gorham, who in 1787 was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention and chaired its early deliberations.

The phrase “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” entered the American Constitution because George Mason of Virginia was unhappy that, as the Constitutional Convention was drawing to a close, the class of impeachable offenses had been limited to “treason or bribery.” Mason wanted a much broader definition. He illustrated his point by arguing that Hastings’s offenses would not be covered by the proposed skimpy language. Mason’s first suggested addition—“maladministration”—was thought too expansive, whereupon he offered, and the convention accepted, that sturdy old English term of art “high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

The beauty of “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” from the perspective of the men of 1787 was that it provided both flexibility and some measure of guidance. Flexibility because it plainly pointed to the parliamentary practice of defining impeachable conduct on a case-by-case basis. Guidance because it incorporated, by reference, 400 years of prior practice on which one could rely in identifying the kinds and degrees of misbehavior that ought to be impeachable.

Moreover, the founders, both during the ratification period and afterward, identified multiple noncriminal acts they believed to be impeachable. At the Virginia ratifying convention, James Madison and Wilson Nicholas said abuse of the pardon power would be impeachable. Impeachment, some founders said, would also follow from receipt of foreign emoluments or presidential efforts to secure by trickery Senate ratification of a disadvantageous treaty. During the first Congress of 1789, Madison even argued that presidents could be impeached for “wanton removal of meritorious officers.”

In the Federalist Papers, Alexander Hamilton made the larger point that impeachment is directed at “political” offenses that “proceed from … the abuse or violation of some public trust.” He was echoed by the foremost of the first generation of commentators on the Constitution, Justice Joseph Story, who observed in his 1833 treatise Commentaries on the Constitution that impeachable conduct is often “purely political,” and that “no previous statute is necessary to authorize an impeachment for any official misconduct.”

Thus, one point on which the founding generation would have been clear was that “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” was not restricted to indictable crimes. Their understanding has been ratified by two centuries of American practice.

The first American impeachment was of Senator William Blount in 1797. Blount concocted a scheme to give Great Britain control of Florida and the Louisiana territories. When it was exposed, the Senate found he had committed a “high misdemeanor, entirely inconsistent with his public trust and duty,” and promptly expelled him. The House then impeached him in five articles alleging betrayals of trust and the national interest, only one of which even arguably alleged a crime. Although there is some debate on the point arising from the phrasing of the Senate’s verdict, most authorities conclude that Blount escaped conviction only because the Senate decided that senators are not civil officers subject to impeachment.

Multiple judges have been impeached, and some removed, for noncriminal abuses or dereliction of office. Judges John Pickering (1803) and Mark Delahay (1873) were impeached for drunkenness (both) or insanity (Pickering). Judges George English (1926) and Harold Louderback (1933) were impeached, wholly or in part, for abusive or biased behavior that brought their courts into disrepute.

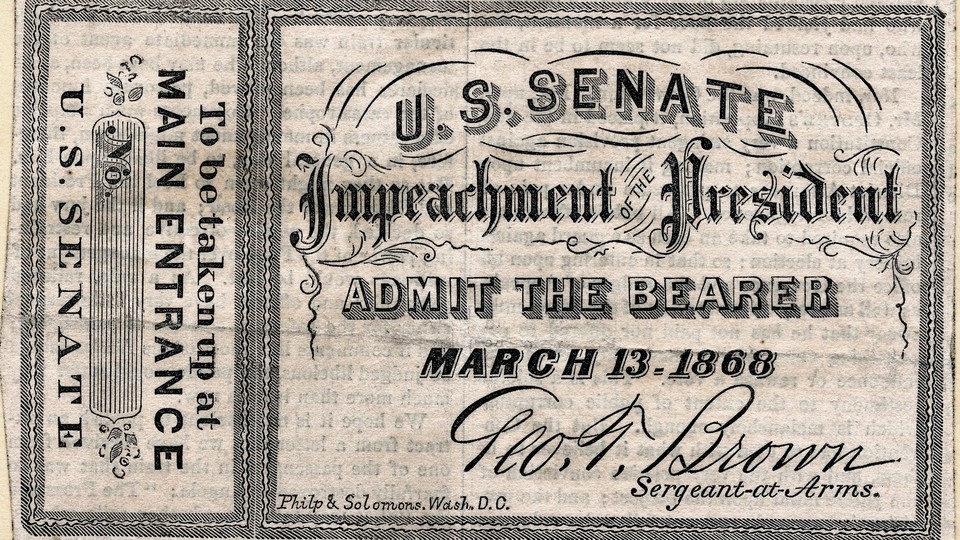

Of the 11 articles of impeachment returned against President Andrew Johnson in 1868, nine involved technically criminal violations of the Tenure of Office Act, but the last and most significant two articles alleged general abuses of presidential authority. Johnson escaped conviction in the Senate by one vote, but no serious historian contends that his acquittal rested on the absence of an indictable crime.

Finally, and most pertinently, the House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment against Richard Nixon: the first for obstruction of justice, the second for abuse of power, and the third for defying House subpoenas during its impeachment investigation. Article 3 obviously did not allege a crime. But even in the first two articles, which did involve some potentially criminal conduct, the committee was at pains to avoid any reference to criminal statutes. Rather, as the committee staff observed in its careful study of the question, “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” is a phrase that reaches far beyond crimes to embrace “exceeding the powers of the office in derogation of those of another branch of government,” “behaving in a manner grossly incompatible with the proper function of the office,” and “employing the power of the office for an improper purpose or personal gain.”

In the end, the best argument against the claim that impeachment requires criminality is not the overwhelming weight of contrary history and precedent, but the sheer dangerous absurdity of the proposition.

The British Parliament invented impeachment and the American Framers poached the institution as a means of saving their respective constitutions from tyranny or catastrophic mismanagement by hereditary, appointed, or elected rulers. It would be daft—and the Framers were not daft—to hobble this “indispensable remedy” by confining it within the idiosyncratic limits of the statutory criminal law available at any given point in time.

Both action and inaction by the chief magistrate, if sufficiently dangerous to the republic, must be impeachable if impeachment is to serve its intended purpose. Even conduct motivated by a sincere and deeply held principle can be a constitutional “high Crime.”

Ben Butler made precisely this point during the Johnson impeachment. Suppose, he imagined, that in 1861, when secession fever broke out, the president had been not Abraham Lincoln, but a man who, whether moved by fear or “an honest, but perverted political theory,” refused to mobilize the Union against the rebellion. Would we say the only remedy in such a case was to allow dissolution of the country because the president’s inaction was no crime?

Or suppose that the nation’s highest court decided Brown v. Board of Education and ordered the desegregation of American schools, and the president ordered out federal troops, not to enforce the order, but to suppress protests by black citizens who sought to take advantage of the order by enrolling in previously segregated schools. Would such defiance of both a co-equal branch and the dictates of common humanity be unimpeachable because it was noncriminal?

Or suppose that a president were to announce one morning that henceforth he would take no account of congressional statutes or administrative regulations and would instead rule by decree. That is, so far as I know, no crime. But does anyone doubt that such a decree would be impeachable?

Or suppose, to bring the case still closer to home, a president were to subordinate himself and the interests of his own country to a foreign power because he or his family could make money by doing so. Or because the foreign country agreed to help him secure reelection. Does anyone seriously suggest that the question of whether such behavior is impeachable turns on the niceties of ethics rules or campaign-finance laws?

Impeachment is not an antique legalism, but an essential tool for securing the safety of the American constitutional order against those who would corrupt or destroy it. An Englishman once said, “Impeachment ought to be, like Goliath’s sword, kept in the temple, and not used but on great occasions.” This aphorism is often cited as a caution against the frivolous unsheathing of impeachment’s blade, but it is also a reminder of the breadth and power of the weapon in times of need. This is such a time.

This story is part of the project “The Battle for the Constitution,” in partnership with the National Constitution Center.