The Movement to Make Texas Its Own Country

Daniel Miller is fighting to divorce his state from the union.

“We have to decide,” Daniel Miller told me, speaking Texan to Texan: “What is right for our people? Do Texans, at a fundamental level, want the right to be governed by themselves?” If Catalonians, Kurds, and Scotsmen deserve their own land, he said, Texans do too.

We were drinking coffee and openly discussing sedition in a bakery in Nederland, Texas, near the terminus of Route 287, which neatly bisects the country, starting in Montana prairie land and ending on the Gulf Coast. As I’d driven to meet him, I’d passed outposts of Whataburger—a fast-food chain so identified with Texas that its sale this year to a Chicago investment bank provoked a minor panic—and oil refineries, whose intricate nests of piping resembled a cube ship from the Borg civilization in Star Trek.

Texas itself is, in some ways, its own civilization. As a schoolboy, some 30 years ago, I learned about a woman in Texas who’d developed a 328-pound ovarian cyst, the largest ever recorded. When I told a classmate, he pumped his fist in the air—the record was ours. Texas pride, which encompasses everything from brisket to football to Willie Nelson to ovarian mega-cysts, is a funny thing.

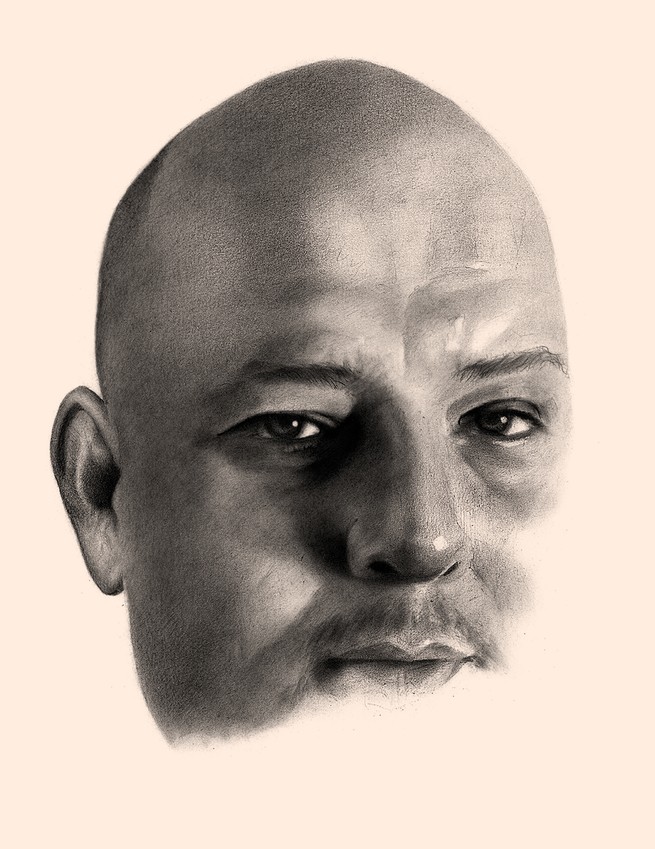

Miller, a big man with a shaved head and a goatee, intends to yoke that pride to a visionary goal. He is the president of the Texas Nationalist Movement, which is devoted to ending Texas’s nearly 175-year experiment with membership in the United States of America. The group, which claims some 300,000 members, demands a referendum on secession and, after what Miller predicts will be an “inevitable” vote to leave, the declaration of an independent Republic of Texas.

Miller makes his case in language inspired by liberation struggles around the globe, and he calls his plan “Texit”—recalling the latest model for secession. Brexiteers claimed that Britain needed the European Union less than the EU needed Britain. Miller argues that Texas sends the U.S. government more in taxes than it receives in federal funds. (To arrive at his numbers, he doesn’t count Social Security benefits, which are paid out handsomely to retirees along the Rio Grande.) Unfettered by federal taxes and regulation, Miller claims, household incomes would sextuple.

Texas’s GDP, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce, is about $1.7 trillion, which would make it the 10th largest economy in the world, ahead of both Canada and Australia. Miller told me the United States’ $714 billion in trade with Canada could serve as an example of how trade relations between Austin and Washington would work. He foresees not a war of secession but a conscious uncoupling followed by cordial relations, with a largely undefended border. The United States has “over a million legal crossings with Mexico and Canada every day,” Miller said, adding that Texas’s border with the United States could remain just as permeable.

Why bother with the federal government, Miller said, when the state government will suffice? The Texas Rangers, the state police force, would take over for the FBI. The Texas Military Department, which includes the state’s Army and Air National Guard, would convert to a national self-defense force.

Miller’s claims invite various retorts. The U.S. Constitution provides no means of secession—legal scholars are unanimous on this—and the last time states tried it, about 3 percent of the American population died in the ensuing war. (Miller insisted, with quixotic certainty, that if Texas voted to secede today, Washington would let it go peacefully.) If Texas did leave, the United States could respond, as the EU may with Britain, by implementing punitive trade regimes to discourage other states from seceding too. Even under a peaceful, best-case scenario, Texas would have to pay an exit tax of at least its share of the $22 trillion national debt and assume an enormous transition cost. It would have to construct a foreign policy ex nihilo, as well as import from Washington many of the elements of government that make that city so detested: debates on abortion, guns, and immigration; bureaucracies such as the Internal Revenue Service; Ted Cruz. (Some secessionists, of course, would be happy to domesticate certain political issues that did not go their way during the Obama administration.)

To Miller, however, the crucial fact is that Texas’s politics would at last be Texas’s own. “The difference is that our decisions will be made here, and we will accept the consequences of those decisions”—and the benefits, too.

In 1961, the journalist John Bainbridge wrote that Texans were “Super-Americans,” exhibiting American traits in abundance—like other Americans, only more so. Miller is, in spite of himself, a classic American type: amiable, self-educated, able to tap baffling and sometimes unnerving reserves of confidence. Born in 1973 in Longview to a teen mother, he met his biological father, the son of Greek immigrants, as a teenager. His mother’s parents, both working-class and only modestly educated, raised him; he called them Mom and Dad. “Dad went to the ninth grade twice, and quit both times when football season was over,” he told me.

In his early teens, Miller became a pen pal of the ex-astronaut John Glenn, who was then a U.S. senator from Ohio. At the age of 18, when Miller decided to run for mayor of his hometown on a sober platform of economic diversification, Glenn connected him with Senator Lloyd Bentsen, whose staff gave Miller advice on political campaigning. (He lost.) Miller attended college without taking a degree. He loads his conversation with references to political and cultural figures. His grandparents wanted an intellectual life for him, he said. “I read like nuts.”

Tragedy struck the family, Miller said, courtesy of the federal government. His grandfather, an ironworker and a Korean War vet, had shortchanged the IRS in what Miller said was an honest mistake. The old man spent the last years of his life fighting with the Department of Veterans Affairs while saddled with a tax-payment plan whose last installment came due just as he was ready to die. In reading the Constitution, Miller found plenty of limited-government wisdom, but none of the justification for what he saw as a behemoth of a state, one he believed persecuted his grandfather. “I saw how incongruent America was with what we believed America was,” he said. “It was like we went to Jack in the Box, ordered a hamburger, and got a sack of tacos.”

For a period of time, Miller voted angrily for anyone, of any party, willing to fight against the federal government. But then he hit on a wilder remedy: What if there were no federal government at all? He joined a small but hardy band of secessionists in 1996. “I set out on a journey that would consume much of my adult life,” he later wrote in a manifesto. Normally jovial, his face grew solemn as he described his conversion. “I decided: I’m going to do this. And I’m going to do this until it’s done.”

Independence movements have been rising and falling in Texas ever since it became a state. When Texas joined the union, in 1845, it had spent nine years as its own country, following its defeat of Mexico in one of a series of underdog victories by revolutionary movements in the Atlantic. But it was a start-up country, never more than a few months ahead of bankruptcy. Mexico had begun raids into Texas territory, and Mexican irredentism was growing. Texas joined the United States for the same reason Latvia, having left the Soviet Union in 1991, joined NATO in 2004: It worried that without a security guarantee, it would be absorbed back into the polity from which it had just secured its freedom.

Just 16 years later, in 1861, Texas tried to secede for the first time, not by declaring independence but by joining the Confederacy. For most of the next century, the forces of secession remained dormant, until they were roused by a militialike movement calling itself the Republic of Texas. As Miller watched supportively from the fringes, members began fighting against the U.S. using that most savage form of modern warfare: nuisance lawsuits. But after the Republic of Texas graduated to violence—in 1997, members spent a week in an armed standoff with Texas Rangers—the movement fizzled. Miller now says “almost nothing” of value emerged from it, other than wider awareness that secession was an option.

For nearly a decade, Miller said, anyone who raised the idea of secession risked being labeled a wacko. He chokes up when recalling the mockery and disdain his secessionism earned him and, by extension, his wife and six children. He worked in computers at the time, but says people treated him “like a domestic terrorist.” After his boss saw a TV segment in which Miller was interviewed, he summoned Miller to his office. “I almost lost my job,” Miller told me. “It felt like I might end up in Guantánamo Bay.”

Finding little support, Miller and a few other true believers undertook a study of the past 70 years of successful independence movements. “We were trying to figure out how to transition this thing into a political movement,” he said. His research led him to the work of a then-obscure New England political scientist named Gene Sharp, who studied nonviolence and later influenced the Arab Spring and the Occupy movement. (When I mentioned that I once met Sharp, who died in 2018, Miller glared at me jealously and said, “Lucky devil.”) Nonviolence sometimes works, Sharp argued, by overcoming what he called atomization—the isolation of individuals who would find courage in numbers. A revolutionary in his room fears being the first one to rebel. But nonviolent tactics such as marches and pirate radio prove to the timid that their cause’s support is deep. A thousand Daniel Millers, each laboring alone, would cower. But a thousand Daniel Millers together on the streets of Austin might win their freedom.

Sharp’s insights on nonviolence have guided Miller ever since. By Texas standards, Miller’s secessionists are practically Quaker. And since he reorganized the movement in 2005 as the Texas Nationalist Movement, its membership has grown quickly. Until 2005, Miller agitated for independence by moonlight. “You’d work 40 hours for the man,” he said, “and 40 hours for the republic.” Eventually he quit to set up a radio station, Radio Free Texas, that plays Texan music and hawks patriotic T-shirts (secede from pop country; nashville sucks).

He claims that “a handful” of state representatives, “a couple state senators,” and “loads” of county- and city-level officials have sworn to support a referendum on independence and to vote for secession. I asked him to introduce me to one, but he declined. “Every one of these guys is afraid to be the first one to stick his head out of the foxhole,” he said.

Before the 2016 Brexit vote, the Texas Nationalist Movement could be dismissed as little more than elevated kitsch. In Brexit, Miller’s group saw proof of concept: a referendum that directly channeled the will of the people. The Leave partisans had bypassed elites. His group had advocated to do the same since its inception. It reinvigorated a dormant canvassing program, with “field organizers engaging the citizens of Texas through standard politicking, block walking, phone banking, and information tables.” Consciousness was being raised.

Or perhaps the consciousness was already there. Miller knows that the fraternal feeling of Texan toward Texan, cultivated in schools and on playing fields, has no rival in other states. Among the supporters of Texas secession—as well as similar movements in California and Hawaii—is Russia, which has long disliked American support for overseas liberation movements, and now enjoys the idea that the U.S. might be bothered by liberation movements within its own borders. Miller said his group regrets accepting funds to travel to a Russian conference on secession and antiglobalism, and that the conference was a waste of time. But he shares Russia’s disgust at American hypocrisy. “The United States has gone out and promoted—sometimes by the use of force—the right of self-determination,” Miller said. “Let’s see if the United States federal government is ready to put their money where their mouth has been on foreign policy for the last 70 years.”

Converting Texas pride into action will require only a nudge, Miller said—and a renaissance in Texas culture (including music) is a vital step. Sentimentality about Texas could translate to an independence referendum, even one with no legal effect. Demonstrating Texas’s will to leave might be enough. How could America ignore a declaration that its second-largest state was participating in the union under protest? How could Texans—even Texans who preferred to remain part of the U.S.—not take umbrage at having their state’s popular will overruled? If Texas nationalism surges, it will be due to just such a bogus feeling of wounded pride—a Texas-size umbrage metastasizing, like an ovarian tumor, on America’s southern border.

After a few hours, Miller had exhausted his secessionist patter, and his fatigue was beginning to show. He’d had a conference call that morning about legislative outreach, and another in the afternoon with a video team. But a revolutionary’s work doesn’t end until the revolution is complete. He sees working the equivalent of an unpaid second job as a moral burden. Only a “psychopath” could watch passively as Texans remain beggared and humiliated by Washington, he said. “I’ll pay the price because I want to win,” he explained. “But then I want to go home. I want to go enjoy the remainder of my life with my wife, and I want to think about my life, post–Texas independence, as belonging to me for once.” Miller added that his first priority after winning the state’s freedom will be to leave it, albeit temporarily, so he can travel to Greece, the land of his ancestors and the birthplace of Western democracy, while carrying a Texas passport.

This article appears in the December 2019 print edition with the headline “The Secessionist.”