Nationalism Is a Form of Love, Not Hate

It is also the foundation of a democratic political order.

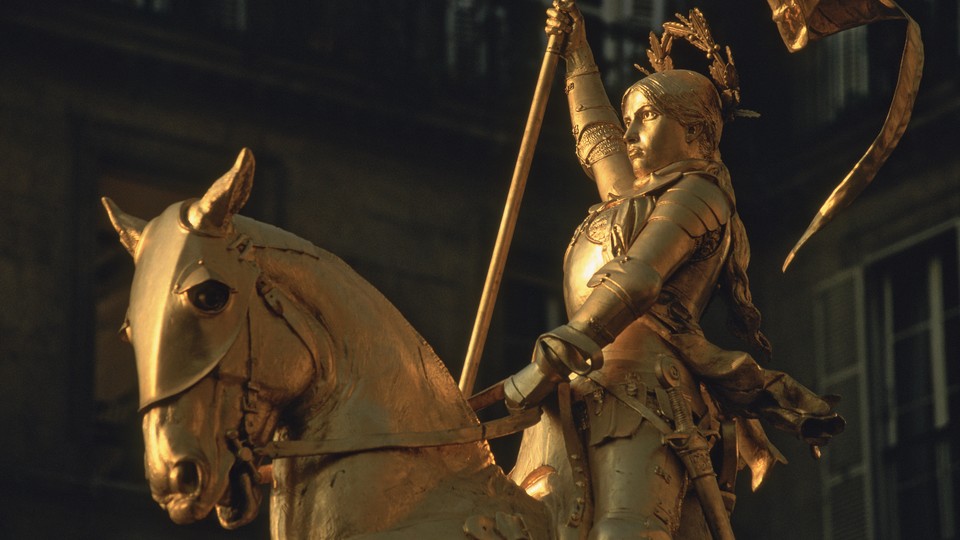

In 1425, a 13-year-old French peasant girl experienced a vision of Saint Michael the Archangel in her father’s garden. It began a journey that would make her a world-famous martyr and transcendent national hero whom Mark Twain deemed “the most noble life that was ever born into this world save only One.”

Joan of Arc had visions that told her to free France from the English, and this was what she set out to do, in one of the least likely stories of martial valor the world has ever known. A slender teenage girl defied every norm of class and gender to convince the authorities that she was born to liberate her country and should be allowed to lead troops into battle. When she did, she won a stunning victory against the English besieging the city of Orléans.

Critics of nationalism contend that it is a relatively recent phenomenon, a contrivance of modern rulers to control and manipulate their populations, and is therefore inherently illegitimate. The Maid of Orléans tells us otherwise.

The Brexit vote and Donald Trump’s 2016 victory, as well as the rise of nationalist governments in Central and Eastern Europe, have swept nationalism to the fore of the public debate, but have not necessarily led to greater understanding. Nationalism is still often assumed to be an inherently nefarious force. It is true that it can be abused for illiberal ends, but the basic impetus for it—for a self-governing people to occupy a distinct territory—is elemental.

Whether in the United States or anywhere else, critics of nationalism would be better advised to hone it for their own ends rather than shun it or pretend it will go away. Nationalism, or at least national feeling, isn’t new or manufactured; the idea is quite old and entirely natural. It’s based not on hatred, but on love—on our affection for home and our own people. It is caught up in culture, in the language, manners, and rituals that set off any given country from another. It represents a deep-seated force that can’t be effaced without government coercion, and even then has proved impossible to wipe out. Empires and totalitarian ideologies alike have failed to eradicate it.

States with a national basis have existed for a very long time. Ancient Egypt constituted a unified state, ruling an ethnically homogeneous people with a distinct culture, for thousands of years. The same was true of China, Korea, and Japan. The basic map of Europe had taken shape by the 12th century. “France, England, and Scotland, the three Scandinavian kingdoms, Aragon, Castile, Portugal, Sicily, Hungary, and Poland had all of them taken their places as units of Latin Christendom by 1150,” the historian Johan Huizinga wrote.

The context for Joan of Arc’s heroism was English kings’ long fixation on attempting to rule France. This precipitated the Hundred Years’ War, which, through bloodshed, famine, and plague, reduced the French population by about half. England’s King Henry V had won his famous victory at Agincourt in northern France in 1415. With his French allies (the Burgundians sided with him, the Armagnacs against), he held Paris and a swath of northern France and had forced the French to recognize his heirs as the rightful rulers of France.

Kathryn Harrison describes the story in the biography Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured. Born a few years before Agincourt, her country divided by civil war and under foreign occupation for 75 years, Joan followed the voices that told her to fight to restore to the throne Charles of Valois, the French heir who had been pushed aside by the English.

She sent a note to the English prior to the battle at Orléans that they should get out of France. If they refused, she assured them with wonderful temerity, “I am a captain of war, and wherever I find your men in France, I will force them to leave, whether they wish to or not. If they refuse to obey, I will have them all killed. I am sent by God, the King of Heaven, to chase you one and all from France.”

The English weren’t overly impressed by their young female interlocutor. She sent another warning in a message tied to an arrow and shot over to the English camp: “I am writing this to you for the third and final time; I will not write anything further.” The English troops yelled back, “News from the whore of the French Armagnacs.” Joan cried the tears of an insulted teenage girl—and soon enough got her revenge.

The Maid of Orléans led the French troops to victory riding a white horse and carrying a 12-foot banner with an image of Christ sitting in judgment. She would eventually be captured and executed by the English, but soon enough, in keeping with her outlandish prediction before she took up arms, Charles VII was crowned in the cathedral of Reims. Her example has endured ever since; more than 500 years later, during World War II, the Free French adopted her symbol, the cross of Lorraine, as their own.

All of this means that it would be impossible to suppress nationalism and foolish to try. The great Italian nationalist Giuseppe Mazzini, the 19th-century writer and activist who agitated for the unification of Italy under a republican government, expressed this feeling: “Our country is our home, the home which God has given us, placing therein a numerous family which we love and are loved by, and with which we have a more intimate and quicker communion of feeling and thought than with others.”

His sentiment underlines how loyalty to nation is ultimately built on a foundation of love—for its landscape, arts, traditions, and people; for, in short, what is ours. Nationalist songs and poems typically aren’t bloodthirsty or hateful, but simply express a devotion to country. The British writer G. K. Chesterton put it well. “Cosmopolitanism gives us one country, and it is good,” he wrote. “Nationalism gives us a hundred countries, and every one of them is the best.”

This is why the nation can make a call on our sacrifice—to kill and be killed—that very few causes can outside of family and faith. The World War I–era tombs of unknown soldiers symbolize this intense, almost mystical identification of citizen-warriors and the nation. The tomb in Arlington National Cemetery is inscribed simply but powerfully, here rests in honored glory an american soldier known but to god; it has been watched over by a sentinel every minute of every day since 1937. Every evening in France, a Committee of the Flame relights a torch at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the base of the Arc de Triomphe. In Great Britain, the unknown soldier rests in Westminster Abbey, the church of kings, underneath the inscription beneath this stone rests the body of a british warrior unknown by name or rank brought from france to lie among the most illustrious of the land.

Any attempt to disrupt these commemorations would be taken as a grave offense against the nation, which depends on—and must honor—the sacrifices of its citizens.

By the way, anyone who thinks that America is immune from nationalism, or that it represents only what’s worst in our history, hasn’t truly grappled with a tradition that runs through Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt, and is inseparable from such high points of our story as the American Revolution and the ratification of the Constitution. Our nationalism is infused with our ideals, but nationalism often has an ideological content.

Indeed, modern nationalism developed in the 19th century as largely a liberal movement, intimately associated with the rise of popular sovereignty over monarchs who considered nations their personal fiefs. It is not just a coincidence that the era of the modern nation-state has overlapped with the rise of democracy.

Having a functioning democracy requires a demos, or a people who feel attached to one another. We are well beyond the era of the city-state, when all free citizens could gather on the Pnyx, the Athenian hillside within sight of the Acropolis, and listen to the likes of Pericles and Alcibiades before voting on important matters of state. Now the nation-state is the best way to delineate a people sharing bonds of language, history, culture, and institutions.

Undergirding the nation is, most important, a common language and an associated distinct national literature. The spark for nationalist movements has often been historians, writers, lexicographers, and folklorists who celebrated and promoted vernacular languages and excavated a glorious literary past. Poets came to exemplify the national traditions and aspirations of their countries: The Irish had W. B. Yeats, the Poles had Adam Mickiewicz, the Zionists had Haim Bialik, and so on.

When common bonds are missing, it spells trouble. In former colonial territories in the Middle East and Africa, proper nation-states struggled to develop, partly as a function of artificial borders. These places weren’t more enlightened or peaceful for their lack of strong national feeling, but the opposite—often blighted by ruinous tribal and ethnic conflict.

Likewise, when a political authority runs against the grain of a nation’s culture and identity, its legitimacy inevitably comes into question. The old multinational empires of Europe—the Habsburg, Ottoman, and Russian empires—all dissolved as their repressive apparatuses gave way and the drive toward national self-determination gained ground. Empires can’t rely on the fellow feeling and social trust that are at the foundation of democracy. John Stuart Mill wrote that such states are beset by “mutual antipathies” and that “none feel that they can rely on others for fidelity in a joint resistance.” He concluded that it is “a necessary condition of free institutions that the boundaries of government should coincide in the main with those of nationalities.”

This has been borne out. Azar Gat, a scholar of nationalism, writes, “While there have been many national states without free government, free government has scarcely existed in the absence of a national community.”

National loyalty gives everyone in society a common interest that is deeper than any specific power struggle. It transcends tribe and sect. It establishes the parameters within which a discrete people and its government can arrive at something approximating the social contract imagined by philosophers such as John Locke. It renders a society, as the philosopher Roger Scruton puts it, in the first-person plural we. Only on this basis is it possible to create citizens with equal rights and reciprocal obligations, living together under the rule of law. This arrangement, in turn, makes possible the social trust that lubricates everyday life and the market economy.

In short, nationalism isn’t just old, natural, deep-seated, and extremely difficult to suppress. It is also the foundation of a democratic political order. Regardless, anyone who believes that it can be easily repressed in favor of some other, supposedly more broad-minded loyalty is profoundly mistaken.

Just ask the English who grappled with a fearlessly patriotic French girl so many centuries ago. They captured her, humiliated and attempted to discredit her, and finally executed her to bury her memory forever, yet the example and spirit of Joan of Arc inspire her countrymen and people around the world to this day.

This article was adapted from The Case for Nationalism: How It Made Us Powerful, United, and Free.