It Wasn’t the Law That Stopped Other Presidents From Killing Soleimani

The Iranian general helped get hundreds of Americans killed—through two administrations. Both declined to kill him.

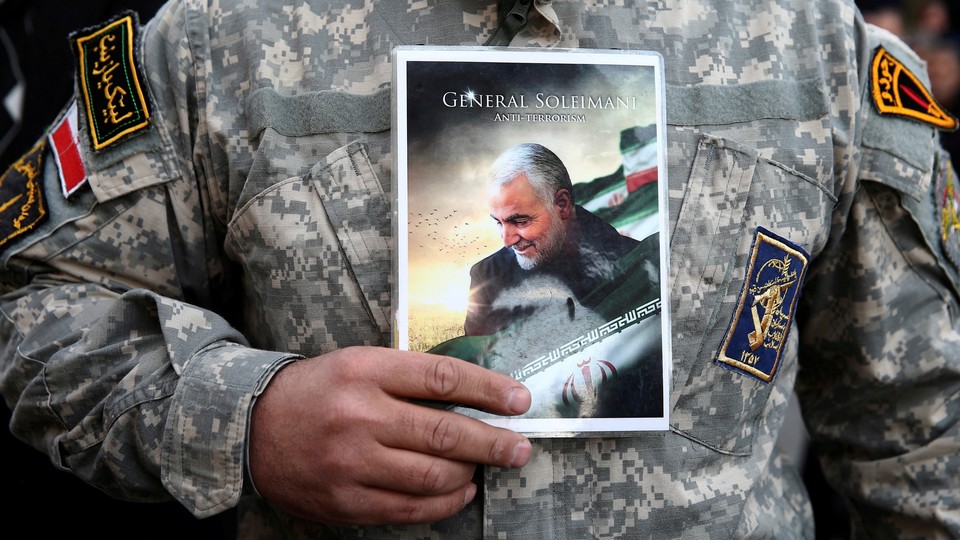

Just about nobody in Washington wants to defend Qassem Soleimani—even if they condemn his killing. He was a terrorist kingpin; he destroyed the lives of countless people across an entire region for more than a decade; he had Syrian, Iraqi, Yemeni, Lebanese, and American blood on his hands. Democratic Senator Chris Murphy slammed what he called an assassination as he tweeted, “Soleimani was an enemy of the United States. That’s not a question.” Representative Eliot Engel, the Democratic chair of House Foreign Affairs Committee, decried the lack of consultation with Congress; he also called Soleimani “the mastermind of immense violence, suffering, and instability.” Much of the litany of Soleimani’s crimes through two presidential administrations prior to Donald Trump’s is well-known.

So why kill him now?

George W. Bush did not target him during the height of the Iraq War, when Iranian-supplied roadside bombs and Iran-backed militias were killing hundreds of American troops. By 2011, that toll had reached more than 600 and Barack Obama was the president; he too declined to hit the general. But at some point Trump, who came into office vowing to pull the United States out from Middle Eastern wars, decided to cross a line two war-president predecessors feared breaching.

This fear wasn’t because of America’s long-standing prohibition of “assassination,” forged during the Cold War to check the excesses of the CIA. Successive administrations since September 11 have interpreted this ban narrowly, arguing that singling out an individual for death on the battlefield doesn’t really count. The ban arose in response to covert CIA plots to, for example, kill Fidel Castro with an exploding cigar during peacetime—essentially, attempting to kill because of political differences, not in wartime self-defense, said Matthew Waxman, who directs the National Security Law Program at Columbia University and served in the Bush administration. The Obama administration used the term targeted killing for strikes on terrorist leaders in overseas battlefields—arguing that they fell under a right to self-defense in an ongoing war against al-Qaeda.

Not everyone is convinced. “These killings cannot be distinguished from unlawful assassination,” Mary Ellen O’Connell, a professor at Notre Dame Law School, told me.

The Soleimani killing would be no more or less legal in this context than that of a nonstate leader just because he worked as a top general, in uniform, for a state. If you subscribe to the idea that targeting an individual combatant in self-defense isn’t the same as an assassination, then Soleimani is fair game—provided you credit Trump’s claim that Soleimani was plotting “imminent and sinister” attacks against Americans. A State Department official on a phone call with reporters noted, “Assassinations are not allowed under law.” But the official argued that this wasn’t one. “The criteria is: Do you have overwhelming evidence that somebody is going to launch a military or terrorist attack against you? Check that box. The second one is: Do you have some legal means to, like, have this guy arrested by the Belgian authorities or something? Check that box, because there’s no way anybody was going to stop Qassem Soleimani in the places he was running around—Damascus, Beirut. And so you take lethal action against him.”

If you believe targeted killings is a sanitized term for assassinations, which have become normalized in the drone-war era but are no less illegal, then targeting Soleimani is a war crime, especially since there’s no formal state of war between the United States and Iran. “Preemptive self-defense is never a legal justification for assassination,” O’Connell said. “Nothing is. The relevant law is the United Nations Charter, which defines self-defense as a right to respond to an actual and significant armed attack.”

Two administrations sidestepped this debate when it came to Soleimani, not as much for legal or moral reasons as for strategic ones. The two sides of this conflict have opted for other forms of confrontation, from proxy fights to sabotage to cyberattacks to sanctions, but they didn’t kill each other’s generals. Now that barrier has been shattered, leaving the world to await Iran’s next move in a game with suddenly higher stakes. From the Iranian perspective, it doesn’t much matter whether the U.S. administration considers Soleimani’s death an assassination or not. He’s still a dead general.

Elissa Slotkin, a Democratic representative and former CIA analyst focused on Shia militias, said in a statement that she’d seen friends and colleagues killed or hurt by Iranian weapons under Soleimani’s guidance when she served in Iraq. She said she was involved in discussions during both the Bush and Obama administrations about how to respond to his violence. Neither opted for assassination.

“What always kept both Democratic and Republican presidents from targeting Soleimani himself was the simple question: Was the strike worth the likely retaliation, and the potential to pull us into protracted conflict?” she said. “The two administrations I worked for both determined that the ultimate ends didn’t justify the means. The Trump Administration has made a different calculation.”

Trump-administration officials have so far declined to specify what exactly prompted that calculation, though Trump said Soleimani was planning to attack American diplomats and military personnel. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told some reporters that “the risk of inaction exceeded the risk of action,” according to The Washington Post’s Dan Lamothe.

The risks of action in other cases have restrained the U.S. from targeting military leaders—for instance, to hold on to the possibility of negotiations, or out of the belief, in Murphy’s words, that “such action will get more, not less, Americans killed.” But action is not unprecedented. “We have [in the past] gone after very, very senior military leaders; usually that would be kind of in the course of an ongoing war,” Waxman told me. During the Iraq War, a congressionally authorized state-on-state conflict, U.S. troops had a “deck of cards” of top most-wanted figures, including senior leaders in Saddam Hussein’s armed forces. During World War II, the U.S. killed the Japanese admiral who plotted the attack on Pearl Harbor.

But in both of those cases, the United States was in a formal state of armed conflict. More recently, as the U.S. has focused on fighting nonstate terrorist organizations, it has also gone after the leadership of those groups. Though Iran has since May staged a series of violent attacks against U.S. allies and interests in the region—culminating, in the past two months, in rocket attacks against U.S. or allied bases in Iraq and the death of an American contractor—no formal war has been declared. And when Soleimani was killed, he died on the soil of a U.S.-allied country, whose government then condemned the attack.

The State Department official conceded the risks in the background call with reporters. “We cannot promise that we have broken the circle of violence,” the official said. But without Soleimani, the official said, “if we do see an increase in violence, it probably will not be as devilishly ingenious.”