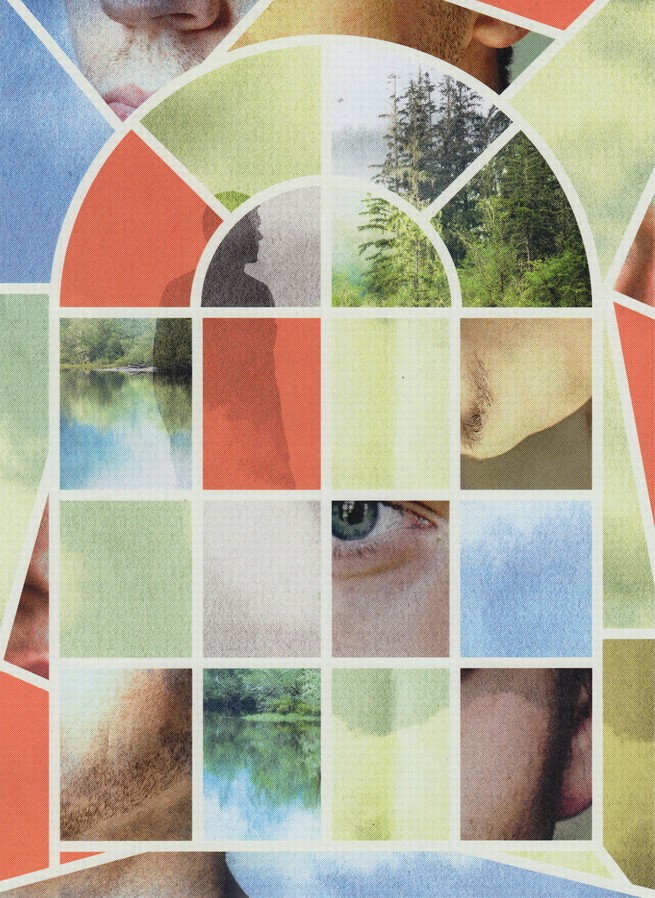

The Art of Second Chances

In Emily St. John Mandel’s disaster-steeped fiction, a derailed life can take multiple forms.

Writing in The New York Times in June 2003, less than two years after the events of September 11 shattered the complacency with which many Americans conducted their lives, the British critic Michael Pye lamented an unlikely casualty of the new era: the ability to occupy ourselves with a superficial novel while sitting in an airport lounge or drifting at 30,000 feet. With tanks now standing guard at London’s Heathrow Airport, what was once an ordinary plane trip had acquired “an element of thoroughly unwanted suspense.” The usual reading material, Pye argued, would no longer do. “We stand in need of something stronger now: the travel book you can read while making your way through this new, alarming world.”

The Canadian writer Emily St. John Mandel used these lines as an epigraph to her second novel, The Singer’s Gun (2010), a book haunted by 9/11. But her entire body of work—her new novel, The Glass Hotel, is her fifth—can be read as a response to Pye’s demand. Mandel’s deeply imagined, philosophically profound reckonings with life in an age of disaster would indeed be appropriate companions alongside a plastic cup of wine and a tray of reheated food (if we’re lucky). But they are equally welcome at home during anxious days of following the news cycle or insomniac nights of worrying about the future. “You can make an argument that the world’s become more bleak, but I feel like we always think we’re living at the end of the world,” Mandel said in a recent interview at the University of Central Florida. “When have we ever felt like it wasn’t going to be catastrophic?”

That sense of cataclysm most dramatically pervades Station Eleven, Mandel’s breakout 2014 novel about a vicious pandemic known as the Georgia Flu that sweeps the globe with astonishing speed (most of those infected are dead within a day or two), killing more than 99 percent of the Earth’s population. With so few people left to keep systems running, civilization collapses. Mandel offers an “incomplete list” of modern essentials that quickly cease to exist: electricity, countries with borders, the internet, fire departments. “No more diving into pools of chlorinated water lit green from below. No more ball games played out under floodlights. No more porch lights with moths fluttering on summer nights. No more trains running under the surface of cities on the dazzling power of the electric third rail. No more cities.” The novel proceeds with its own impeccable, funereal logic. A nearsighted man who loses his glasses is unable to replace them; after the world’s gasoline supply goes stale, pickup trucks, retrofitted with wheels of metal and wood, are pulled by horses. The immersion in Mandel’s fictional world is so complete that more than once while reading Station Eleven, I found myself looking around to make sure life as I knew it still continued.

Although the details of the pandemic are sketched in a few heartbreaking scenes, Mandel is less interested in the unfolding of the catastrophe itself than in its impact on the survivors and their descendants, who are still trying to make sense of it 20 years later. Dystopic discontinuity, though, turns out not to be her theme at all. Twenty-eight-year-old Kirsten, one of the book’s multiple protagonists—their nonlinear narratives appear in shards that the reader pieces together—is an actor with the Traveling Symphony, a troupe that makes its way between towns with names like New Phoenix, performing Shakespeare’s plays and classical music, because “people want what was best about the world.” An older businessman named Clark, who gets stranded in an airport during the crisis and builds an encampment there with a group of fellow passengers, transforms an airline lounge into the “Museum of Civilization,” filled with artifacts of the old world that no longer have use: a driver’s license, a credit card, a pair of high-heeled shoes. Everyone in the post-disaster world is tormented by the ever present reminders of luxuries and conveniences they no longer enjoy, even people who are too young to remember them. (Kirsten, whose memories of her childhood are hazy, at one point wonders whether refrigerators had light bulbs inside.) But the book ultimately makes a beautiful argument for the endurance of art—music, theater, literature—in drastic times. “Because survival is insufficient,” the quote painted on the Traveling Symphony’s caravan proclaims. (Yes, it’s from Star Trek.)

A finalist for a National Book Award, Station Eleven is one of the most imaginatively coherent novels I have read in recent years, skipping among characters and time periods with complete authorial control as it builds its own fully realized universe. For this reason, I was initially astonished, several chapters into The Glass Hotel, to recognize a minor character from that novel: Leon Prevant, the shipping executive who employs as his assistant the young Miranda, an artist who spends her downtime in the office drawing the graphic novel about a castaway in outer space that gives Station Eleven its title. Later he is joined by Miranda herself, whom Mandel’s readers will remember last encountering on a beach in Malaysia, succumbing to the delirium of the Georgia Flu. Yet here she is, alive and well, her destiny altered but all her other characteristics intact. What are they doing in this new novel? The answer, it emerges, is essential to Mandel’s fictional project, which The Glass Hotel expands in surprising and powerful ways.

If Station Eleven is a mosaic—we see the outlines of the picture nearly at once, but precisely how the pieces fit together appears later—The Glass Hotel is a jigsaw puzzle missing its box. At the book’s start, what exactly it is about or even who the major figures are is unclear. The novel opens with a mysterious, fragmented monologue dated 2018 and titled “Vincent in the Ocean,” spoken by someone of indeterminate gender who could be either dreaming or drowning; the first line is “Begin at the end.” That section breaks off abruptly and the next jumps nearly two decades earlier, to late December 1999, with the focus on Vincent’s half brother, Paul. At age 23, he’s finally made it to the University of Toronto after years of trouble with drugs, but he’s on the cusp of flunking out in his first semester. One night at a club, he accidentally slips an acquaintance a bad pill, and the boy dies on the dance floor, sending Paul into free fall.

Five years later, Paul seems to have his life back together. He and Vincent are on the night staff of a luxury hotel newly constructed on a remote British Columbia island where they spent their early childhood—a traumatic interlude, in different ways, for both of them. (We learn that Vincent, the product of an affair that ruptured the marriage of Paul’s parents, is female—she was named after Edna St. Vincent Millay—and was sent away at age 13, after her mother disappeared one afternoon while canoeing, either by accident or by suicide.) Now, after the half-siblings have been reunited, someone scrawls a threatening message late one night on one of the hotel’s huge glass windows with an acid marker. That the culprit is Paul is immediately obvious, both to the others at the hotel and to the reader. But the meaning of the message Paul wrote, and the reason he wrote it, will remain obscure until nearly the novel’s end.

How many second chances, how many reinventions, how many transformations are possible for any given person? What are the forces that keep us moving along our current path and not a different one? In Station Eleven, in which the course of everyone’s life is altered by the disaster, a violinist with the Traveling Symphony contemplates the idea that an infinite number of parallel universes could exist, including ones in which the pandemic was less fatal or never took place, and in which he might have grown up to be a physicist, as he had planned. In The Glass Hotel, the forces that catapult characters from one possible life into another are the more usual ones: crime, tragedy, marriage. Sometimes we choose to plunge into a different world; sometimes a different world chooses us.

The night Paul defaces the window, Vincent meets the hotel’s owner, Jonathan Alkaitis—an obscenely rich financier, recently widowed—and the once rebellious teenager slips into a new life with him almost as easily as putting on a new pair of shoes. She thinks of the world he inhabits as “the kingdom of money,” and the two chapters chronicling her relationship with Alkaitis are titled “A Fairy Tale.” But all fairy tales come to an end. Vincent’s stay in the kingdom will be temporary. (Alkaitis works in the Gradia Building, a name that readers of Station Eleven will recognize as a sign that something terrible is taking place inside.) Leon Prevant, the shipping executive from Station Eleven, will find his circumstances utterly altered by the loss of his life savings. Instead of retiring in contentment to Florida, he and his wife abandon their home and take to the road in an RV, joining a “shadow country” inhabited by transients like themselves.

And Alkaitis, after committing crimes that earn him a lifetime prison sentence and the contempt of everyone he was once close to, finds respite from his daily existence in elaborate fantasies about how things might have gone differently—fantasies that occupy more and more of his waking hours and ultimately threaten his grip on reality. He comes to view the line between memory and imagination as a “permeable border”; he can exist simultaneously in one world and another. Other characters similarly wrestle with the notion that two contradictory ideas can coexist, if uncomfortably. Oskar, one of Alkaitis’s employees, will testify in court that “it’s possible to both know and not know something.” As a defense for what Alkaitis did, that is inadequate, but in some ways it is also true.

In contrast to the elegiac mood of Station Eleven, with its longing for a never-to-be-recovered past, The Glass Hotel moves forward propulsively, its characters continually on the run. Still, the harder they try to escape their histories, the more persistently they are pulled back, often by visions of the people they’ve wronged. These ghosts are not emissaries come to do malice or wreak vengeance, as we usually imagine them to be; they are physical manifestations of guilty consciences. (Station Eleven dealt almost humorously with the idea of a spirit world: “Are you asking if I believe in ghosts?” one character says. “Of course not. Imagine how many there’d be” is the response.) They are also an anchor to the past, however unwanted that may be, especially for those who have left behind a life they would be happier forgetting.

Oskar, Alkaitis’s employee, calls his own fantasies of how things might have gone differently a “ghost version” of his life. Alkaitis calls his alternative version a “counterlife,” which Mandel also uses as a title for the latter parts of his story. It’s an explicit reference to Philip Roth’s novel of the same title, in which multiple characters experience different versions of their own lives, some of which are chronicled in a manuscript-within-the-book. Among other things, the device functions to poke fun at some readers’ assumptions that Roth’s books are autobiographical—an alternative version of his own life.

Mandel’s purpose, as I understand it, is different. “We move through this world so lightly,” Leon’s wife says at one point, a remark that could refer both to how unencumbered the two of them are (few possessions, no family) and to the human condition more generally, each individual life ever able to alter its orbit in an unpredictable direction. If anything can happen in life, if anything is possible, then the novel form—which takes those possibilities and multiplies them on a metaphysical scale—becomes the ultimate way to express those variations. That’s precisely why Mandel has brought back characters from her previous novel and spun them in a new direction: to demonstrate the infinite possibilities available to a writer of fiction. (David Mitchell is another contemporary novelist who has used this technique to similar effect.)

The structure of The Glass Hotel is virtuosic, as the fragments of the story coalesce by the end of the narrative into a richly satisfying shape. There are wonderful moments of lyricism, such as the monologue by Vincent that both opens and closes the novel, and another section titled “The Office Chorus,” narrated by a group of Alkaitis’s employees—an especially brilliant touch. But for the most part Mandel’s language is understated, fading almost invisibly to serve the familiar pleasures of character and plot. Despite the initial disorientation of its kaleidoscopic form, The Glass Hotel is ultimately as immersive a reading experience as its predecessor, finding all the necessary imaginative depth within the more realistic confines of its world.

In the first scene of Station Eleven, an actor playing King Lear dies onstage during the production, collapsing art into life. As the novel reminds us, many of Shakespeare’s plays were originally performed against the backdrop of plague outbreaks, in which he likely lost members of his own family. One can imagine that his audiences came to the theater seeking distraction from their moment of catastrophe as well as insight into how to understand it. In our own fractured times, omniscient narrators have come to be viewed with suspicion, and an experimental minimalism often seems to be the only way to describe our lives now. Mandel’s affirmation that a somewhat old-fashioned fictional model is not only relevant to our alarming new world but also deeply appropriate for it manages, remarkably, to feel both consoling and revolutionary.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.