Why I Fear a Moderate Democratic Nominee

Some Democrats are afraid of nominating a progressive, but a moderate may be more likely to ensure Trump’s reelection.

Posts kept coming from Black Matters US, from its accounts stationed at seemingly every corner of the internet in 2016. Twitter. Instagram. YouTube. Facebook. Tumblr. Google+. A news site. Google Ads. PayPal for donations. A podcast offering “strong Black voices.”

Black Matters US posted a steady diet of images, of sayings, of articles, of videos that made black people feel good about being black and feel angry about being black in America. As trust built, posts also whispered, “Our Votes Don’t Matter” and “Don’t Vote for Hillary Clinton” and “A Vote for Jill Stein Is Not a Wasted Vote.”

These whispers came from Russian operatives, screaming into history the true mission of Black Matters US accounts—to troll black people into not voting for Clinton in the 2016 election. Clinton already had a “problem with young black Americans,” especially those reeling from her video calling them “super-predators” in 1996. But her problem exploded into a crisis as Russian trolls relentlessly bonded her to racism and police brutality, the two most important problems facing the country, according to young black Americans in 2016. Russian operatives portrayed her as the devilish ward of the hell Donald Trump said black people were living and dying in. Weeks before the vote, a Black Matters US account posted doctored pictures of Clinton captioned “Satan’s daughter” and “The root of all evil.”

A two-year investigation into Russian interference by the Senate Intelligence Committee concluded in 2018 that “no single group of Americans was targeted ... more than African-Americans.” And no single group of African Americans was targeted more than young African Americans. Russian operatives knew—even if many Americans did not—that young black voters can swing presidential elections. Young voters and voters of color—and especially young black voters—are more likely than older voters and white voters to swing between voting Democrat and not voting (or voting third party). They are America’s other swing voters—distinct from white swing voters shifting between voting Republican and Democrat (or Republican and not voting), distinct from nonvoters of all races who never vote.

No one will ever pinpoint the precise impact of Russian trolling on the 2016 presidential election. But that year, a decisive number of other swing voters shifted away from the moderate Democrat and into not voting (or voting third party). A decisive number of white swing voters shifted away from the moderate Democrat and into the arms of Trump. These swings away from the moderate Democrat were factors in the Democratic Party’s stunning loss to Trump.

Now moderate Democrats are calling for a rematch against Trump in the 2020 election, claiming they are the most electable. The thought is haunting me, like Trump’s hell. As much as moderate Democrats fear that nominating a progressive will ensure Trump’s reelection, I am haunted by the fear that nominating a moderate will ensure Trump’s reelection.

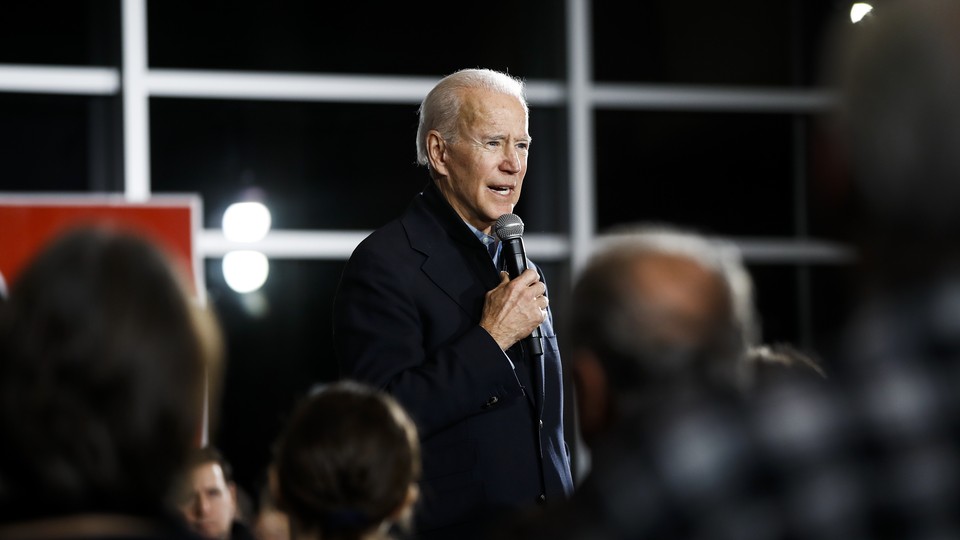

Days before Halloween, even a group of “pro-business Democrats” were doubting the electability of former Vice President Joe Biden and Mayor Pete Buttigieg. They longed for Clinton to jump in, rightly recognizing her as a stronger presidential candidate than these two leading moderates. If Clinton lost to Trump in 2016, how could these weaker moderates defeat a stronger Trump in 2020?

It is a legitimate question, just as it is legitimate for moderates to ask: When has a democratic socialist or a woman calling for structural change ever been elected U.S. president? But when had a Barack Obama or a Donald Trump ever been elected U.S. president?

It is legitimate for moderates to fear that a progressive at the top of the ticket will imperil the reelection chances of House Democrats who won Trump districts during the 2018 midterms. But how can moderate representatives warn against a progressive nominee at the same time they expect progressive representatives to run with a moderate nominee? Both would have difficult tasks in November: moderates winning Trump districts despite the progressive nominee; progressives attracting alienated progressive volunteers and voters in swing states despite the moderate nominee.

It is legitimate for moderates to be concerned about progressive policy proposals driving away some moderates and driving up voting rates within Trump’s conservative base. But where is the concern about all the white swing voters Clinton lost in 2016, even as she failed to turn out the Democratic base? Where is the recognition by moderates that public support for progressive policies has reached a 60-year high?

Moderate fears of a progressive losing to Trump are valid. But progressive fears of a moderate losing to Trump are valid too.

When moderate Democrats assure us that they would win back more white swing voters than progressive Democrats would, I am haunted by the thought that the evidence is hardly so reassuring. I see moderate candidates struggling with younger voters, who are more likely to favor progressive policies, and are more likely than older voters to stay home or vote third party if they don’t like the Democrat. The leaders of nine progressive organizations recently told The Atlantic that a Biden nomination “would trigger a huge deflation in enthusiasm, and a shrinking ... volunteer pool.”

Already “Russians are repeating the same tactics” of deflating voters. Other state actors have joined the fray, and “the United States has no national strategy to counter foreign influence.” American trolls and bots have evolved since 2016, and reportedly may pose a greater threat in the 2020 election. The steepest declines in voting among black people in 2016 were among young black men, and Trump is tailoring his pitch to black men. The election will, in part, hang on whether young voters and especially young black voters will be willing and able to run the gantlet of intense trolling and voter suppression to cast a ballot for a moderate Democrat they may not like. I am haunted most of all because the only thing we can safely predict about an election with Trump is that we can’t safely predict anything about an election with Trump.

I don’t prefer the misleading term moderate (or progressive for that matter). Self-identified moderates, independents, and undecided voters are not necessarily centrists. But there are Democratic candidates claiming that they are best equipped to win these moderates, independents, Republicans, and undecided voters. There are candidates opposing Medicare for All, free public college, the Green New Deal, and a wealth tax. I will call these candidates moderates. And these are the Democrats I fear will lose to Trump.

I am not alone. Nearly one-third of Democratic-primary voters fear their party could lose the presidential election if their nominee is not progressive enough. A relatively equal number of Democratic-primary voters fear their party could lose if their nominee is not moderate enough. But it seems like moderate fears have received the most airing. Every time I looked up over the past year, I saw broadcasts of “stark” warnings like “The latest wave of far-left ideas ... could lead to electoral disaster in 2020.” I heard moderate candidates like Biden saying, “Show me the really left-left-left-left-wingers who beat a Republican.” After stepping off a summer debate stage, Senator Amy Klobuchar said on CNN, “People [who] are watching right now” are “moderate Republicans, and we need to win them to win the election.” In The Atlantic, Yascha Mounk urged Democrats to win back those Obama-to-Trump voters who “made a real difference” in the 2016 election.

Mounk is right. But maybe the candidate of change—no matter his or her party—is the most attractive to these all-important Obama-to-Trump voters, almost all of whom are white. It may have been their campaigns of change, when compared with Mitt Romney and Clinton, that caused Obama and Trump to attract the same white voters. Even their original campaign slogans fit together: Yes, we can make America great again.

After the 2016 election, a young white independent in Michigan said Obama was “really likable” and Trump earned her vote by being “a big poster child for change.” After Obama, Clinton lost ground among young and liberal working-class white voters, the two groups Democrats probably have the best chance of winning back from Trump—and the two groups moderate Democrats struggle to attract.

In 2016, Trump managed to win 20 percent of liberal white working-class voters, and 38 percent of those who desired policies more liberal than Obama’s policies. How? Obama and Trump “had the same winning pitch to white working-class voters,” according to a New York Times analysis. Obama and Trump successfully cast Romney and Clinton as dismantlers of companies and outsourcers of jobs, and themselves as the defenders of the forgotten people. And, Trump added, they have been forgotten because they are white.

Working class (and non-working-class) white voters were more likely to switch from Obama to Trump if they embraced racist ideas. Maybe Obama’s more liberal economic and foreign-policy appeal—when compared with Romney—kept white racist ideas at bay in his 2012 voters. Maybe Trump inflamed their racist ideas in 2016, while being less conservative on economic and foreign-policy issues than past GOP nominees. Maybe a progressive candidate can better expose Trump’s conservatism and corruption on economic and foreign policy to winnable young and liberal white swing voters, which could break their racist allegiances to Trump, which perhaps explains why Senator Bernie Sanders currently leads Trump by the widest margin of all Democratic candidates. Maybe a pro-diversity, pro-corporate, and hawkish moderate Democrat will again alienate winnable white swing voters in 2020.

Maybe it is strategically unwise to build a presidential candidacy based on winning back a sizable number of white voters who supported Obama and flipped to Trump. Roughly seven in 10 Obama-to-Trump voters approve of Trump’s job performance, according to a recent Morning Consult poll of these voters in the swing states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. How can anyone who is serious about defeating Trump think Democrats should nominate a candidate on the theory that he can win back voters who Morning Consult says “resemble Republicans” and who overwhelmingly approve of Trump—over a candidate who can win back voters who “resemble Democrats” and who overwhelmingly disapprove of Trump? Roughly seven in 10 other swing voters—those who voted for Obama in 2012 and did not vote in 2016—disapprove of Trump in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Morning Consult called them “low-hanging electoral fruit” in three states Clinton lost by less than 80,000 votes combined.

The low-hanging fruit is disproportionately composed of young voters, and especially young black voters. Democratic primary voters should value candidates’ performance with these other swing voters as much as they value their performance with white swing voters. Sanders and Senator Elizabeth Warren are running first and second among voters under 35, according to the latest national poll by Quinnipiac University. Among young black voters, Sanders is outpacing Biden by double digits. Only Warren and the businessman Andrew Yang register more than 1 percent support among this crucial group of swing voters. Black support—young or old—for Buttigieg and Klobuchar is nearly nonexistent—as is their chance of defeating Trump without heavy black support.

Young black swing voters who are not supporting Biden are more likely to be progressive and less likely to identify as Democrats than their elders. They look at Biden’s record—from pushing “tough on crime” and welfare-reform legislation to mistreating Anita Hill during the Clarence Thomas hearings to demeaning black parents—and are repelled. Like Clinton’s super-predator video, I fear Biden’s record can push the other swing voters into not voting.

My fear is personal. Russian trolls attempted to coerce me into not voting for Clinton in 2016. (It didn’t work.) I vaguely remember Black Matters US posts on Facebook and Twitter. On March 26, 2016, someone tweeted about Bill O’Reilly blaming black men and boys “for their own deaths” and cops brutalizing a black student. Posts on its news site praised the Green Party’s vice-presidential nominee, Ajamu Baraka, as a “Black hero” who “has fought for Black freedom.”

This time around, one recent report identified five ostensibly pro-black social-media campaigns that could lead black voters away from voting for the Democrat, with trolls and bots extending their influence. The Democratic Party is particularly worried about American Descendants of Slavery, Candace Owens’s Blexit, and Foundational Black Americans.

But Democrats should be more worried about a moderate nominee being out of touch with winnable voters. If the 2018 midterm elections are any indication, moderate Democrats may also be out of touch with winnable Obama-to-Trump swing voters, according to data from Sean McElwee and Brian F. Schaffner. Eighty-three percent of Obama-to-Trump swing voters who switched back to the Democratic Party in 2018 support Medicare for All, nearly mirroring the overwhelming support among other swing voters who voted Obama, didn’t vote in 2016, and then voted for Democrats in the 2018 midterms. These two groups also opposed Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement, supported a $12 minimum wage, and backed a millionaire’s tax at similarly high rates. These two seemingly distinct groups of swing voters (one prototypically white, the other prototypically young and black) may be in line with each other on economic, foreign-policy, and climate issues—and crucially, also may be most closely aligned with progressive candidates. This pumps the heart of electability—any progressive nominee would have clear pathways to two of the most important groups of swing voters whom Democrats lost in 2016.

But the pathways of prospective nominees diverge on race. Warren and Sanders may not be sufficiently antiracist for some young voters and young black swing voters—neither has been a force against racism and police brutality during their political career. Warren and Sanders may not be sufficiently racist for white swing voters—both are trying to be a force against racism and police brutality on the campaign trail. Trolls will no doubt transform Warren and Sanders into anti-black demons, as they will any moderate nominee. Trump will no doubt transform Warren and Sanders into anti-white demons, as he will any moderate nominee. But unlike the moderates, Warren and Sanders have built their candidacies on the “big, structural change” these two groups of swing voters seemingly favor. That could keep them—and the country, and the world—out of the clutches of Trump for another four years.

But anxiety and fear rule Democrats these days. Anxiety and fear should be hurling us toward the evidence and changing our beliefs. But whenever we are overladen with anxiety and fear, it is easier to brush aside the uncomfortable evidence and lay down comfortably on our old bed of beliefs. And there may be no more cherished Democratic belief than the primacy of the electable white moderate.