The End of What, Exactly?

President Trump’s impeachment trial in the Senate was a milestone in jaded bureaucracy.

The impeachment trial of President Donald Trump drew its last breath of suspense just after 1 p.m. today.

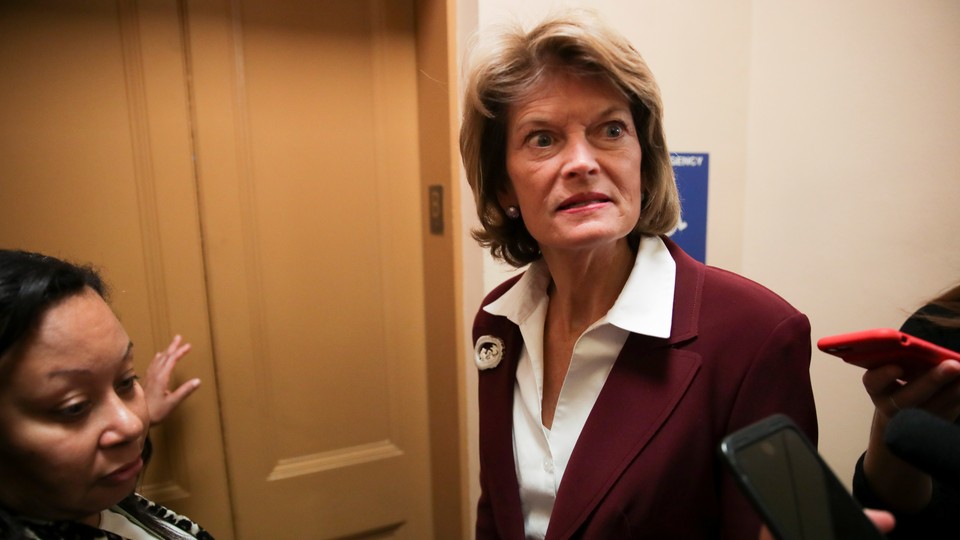

That’s when Senator Lisa Murkowski, Republican of Alaska, and the Democrats’ sole remaining hope for subpoenaing witnesses or documents, announced her unwillingness to do so in a withering attack on the integrity of the institution that her party leads.

“Given the partisan nature of this impeachment from the very beginning and throughout,” Murkowski said in a written statement, “I have come to the conclusion that there will be no fair trial in the Senate. I don’t believe the continuation of this process will change anything. It is sad for me to admit that, as an institution, the Congress has failed.”

Had Murkowski supported subpoenaing witnesses, the vote on the matter would have been a 50–50 tie, and under Senate rules would have failed. But Democrats had held out hope that Chief Justice John Roberts might intervene to break it, and that was too much for Murkowski, who first joined the Senate when her father, Frank, became governor and appointed her in his place. “We have already degraded our institution for partisan political benefit,” she said, “and I will not enable those who wish to pull down another.”

Hours later, the full Senate voted 49–51 against calling witnesses. “The motion is not agreed to,” Roberts said at 5:45 p.m. ET.

To be sure, Murkowski, who is routinely one of the handful of GOP senators who offer the slightest challenge to Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s iron rule, lashed the impeachment articles from the Democratic House as “rushed and flawed.” Without mentioning her by name, Murkowski also scolded her colleague Elizabeth Warren, Democrat of Massachusetts, whose late-night question to the House managers yesterday demanded to know whether “the fact that the Chief Justice is presiding over an impeachment trial in which Republican senators have thus far refused to allow witnesses or evidence contribute[s] to the loss of legitimacy of the Chief Justice, the Supreme Court, and the Constitution.”

But even if her tears were crocodilian, it was the harshness of Murkowski’s criticism of the Senate itself that stood out. Her condemnation came at a moment when McConnell’s years-long legacy of hyper-partisanship, unremitting obstruction of Barack Obama, and unswerving loyalty to Donald Trump and his caucus’s raw political interests crystallized into a profound upending of the norms and procedures of the body he purports to revere.

After the House impeached Trump in December, McConnell took to the Senate floor to bemoan what he called an affront to history. “Historians will regard this as a great irony of this era,” he said, “that so many who professed such concern for our norms and traditions themselves proved willing to trample our constitutional order to get their way.”

Trampling order is a relative thing. McConnell himself has now ensured the only impeachment trial in Senate history that won’t have called witnesses. And until Murkowski and others forced him to change course, he had initially proposed not to automatically accept the documentary record compiled in the House as evidence in the Senate.

It is not necessary to romanticize the history of the Senate to acknowledge that something profound about it has changed. In the 1850s, it was the Senate that temporized America’s original sin of slavery in ways that all but guaranteed the Civil War. For the first half of the 20th century, the chamber was in the grip of southern racists who perpetuated vicious Jim Crow segregation.

But beginning with the civil-rights acts of the 1960s and continuing through Vietnam, Watergate, the CIA’s abuses of domestic and international intelligence, Iran-Contra, Bill Clinton’s impeachment, and the Senate Intelligence Committee’s unsparing investigation of the George W. Bush administration’s torture program, the Senate—in moments of great national peril—has generally risen to the occasion in at least some halting, lurching, imperfect, but still bipartisan way.

Now many believe it has unequivocally failed.

“I mean, I saw great leaders like Howard Baker, who was one of the greatest leaders we ever had,” Patrick Leahy, the Democrat from Vermont who is the Senate’s senior member, told me today. He was referring to the Republican from Tennessee who became a reluctant opponent of Richard Nixon in Watergate, and whose old seat is now held by Lamar Alexander, who all but assured the outcome of the debate on witnesses late last night when he announced that he was opposed to calling any.

Leahy is the last of the so-called Watergate babies elected to the Senate in 1974, and when I buttonholed him in the Capitol’s basement subway, he ticked through the long list of bipartisan leaders under whom he has served. “Bob Dole and George Mitchell, working so closely together, Democrat and Republican, the leaders working things out,” he said. “Like Trent Lott and Tom Daschle did, Mike Mansfield and Hugh Scott. I was there with all of them, and I’ve always felt the Senate should be the conscience of the nation. And we’re not sure [sic] the conscience.”

As a new reporter in Washington a quarter century ago, I watched the collapse in the Senate of Bill and Hillary Clinton’s grand effort to overhaul the nation’s health-care system. One spring day in 1994, Dole, then the Senate’s Republican minority leader, passed a note to his longtime Democratic friend Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York, who as the powerful chairman of the Senate Finance Committee had jurisdiction, asking, “Pat, Are we ready for the Moynihan-Dole Bill?” But the Clinton White House said no compromise, the Republican House leader Newt Gingrich said no dice, and Dole, who wanted nothing so much as to win the Republican nomination for president in 1996, realized he had to give up. Long-shot efforts at compromise by John Chafee, a Republican from Rhode Island and veteran of Guadalcanal who had been John F. Kennedy’s Navy secretary, and John Breaux, a laissez les bon temps rouler Democrat from Louisiana, also came to naught. Months later, the Democrats lost both houses of Congress and, arguably, nothing in Washington has ever been quite the same.

More recent changes have accelerated the trend. The late Senator John McCain of Arizona used to delight in introducing me or another of my colleagues as “a communist reporter from The New York Times,” but he meant it as a joke. His successor, Martha McSally, recently called CNN’s Manu Raju “a liberal hack” on camera while refusing to answer his question in a Senate hallway, and she was dead serious.

Chuck Schumer, the Democratic minority leader whose 10-day battle for witnesses is now over, has almost perfectly straddled the change. He told reporters this morning that “the president’s acquittal will be meaningless, because it will be the result of a sham trial” that will leave “a permanent asterisk,” one “written in permanent ink,” on Trump’s record.

One of Schumer’s first tasks upon his arrival in the Senate 21 years ago was to be a judge during Clinton’s impeachment—a trial in which 10 Republicans voted not guilty on the article charging the president with perjury, and five joined the unanimous Democrats to vote not guilty on a second count charging obstruction. When I asked him after his news conference today whether he’d ever imagined that the Senate would devolve so completely into tribal camps, he just sighed.

“Well, it is extremely partisan, and the president, and Republican obeisance to the president, has really made it even more partisan and nasty than it’s ever been,” Schumer said. Has this trial weakened the institution? “Yes!” he said, before turning away and adding, “That’s all.”

In his own last-ditch argument in favor of calling witnesses today, the House’s lead impeachment manager, Representative Adam Schiff of California, made a similar point. Not summoning witnesses “will be a very dangerous and long-lasting precedent that we will all have to live with,” he told the senators. Schiff called Trump’s “wholesale obstruction” an “attack on congressional oversight, on the co-equal nature of this branch of government, not just on the House but on the Senate,” and their ability to serve as a check on the executive.

The House Intelligence Committee chair received an unsought assist from Trump’s former White House Chief of Staff John Kelly, who said in an interview yesterday that the Senate would forever be known as a body that “shirks its responsibilities” if the trial concludes without calling witnesses.

Those were strategic appeals to a body infamously proud of its role and protective of its prerogatives, but they fell on deaf ears. As the trial got under way 10 days ago, McConnell sought to put the House managers and their demands for witnesses in their place, in no uncertain terms. “As I have been saying for weeks,” he said then, “nobody—nobody—will dictate Senate procedure to U.S. senators.”

That much is now indelibly clear. What Mitch McConnell has been able to dictate—not just to the Senate, but to the millions of Americans still inclined to repose faith in it—is a murkier and more haunting question.