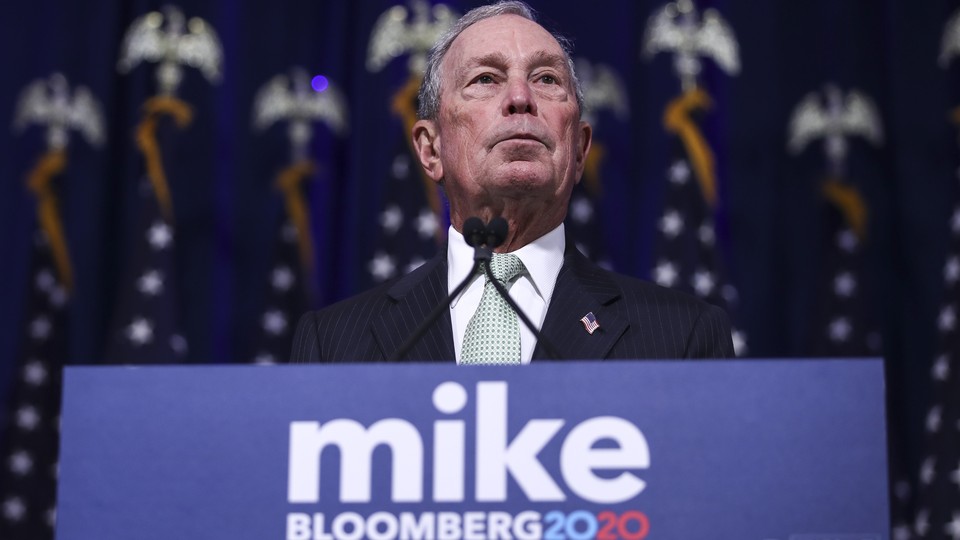

Democrats Are Freaking Out About Mike Bloomberg

"The answer to one Republican New York billionaire is surely not going to be a slightly richer Republican New York billionaire,” one Biden ally said. “It's laughable we even have to say that out loud."

Imagine a Democratic nominee who’s a socialist and not even a member of the party.

Now imagine a Democratic nominee who’s a billionaire businessman who spent his way into contention.

It might be time to start preparing for mayhem.

Bernie Sanders is well positioned to sweep Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada—“a domino effect,” Representative Ilhan Omar of Minnesota predicted at a campaign event for the Vermont senator on Saturday. His aides believe that they’ll be able to bring in the skeptics, and that “the haters will shut up when we win,” as Representative Rashida Tlaib of Michigan put it on Friday night at another event for him, as she led booing of Hillary Clinton. They don’t just insist that Sanders will beat Donald Trump; they say he could scramble the electoral map. They say everyone who thinks he’d be easy pickings for Trump is falling for modern-day red-baiting, and missing Sanders’s high favorability ratings among Democrats.

“The elites who are freaking out are the 1 percent,” Ari Rabin-Havt, one of Sanders’s deputy campaign managers, told me in between canvassing stops in Iowa last week. “I might not be a math professor, but 99 is greater than 1.”

Over at Mike Bloomberg’s campaign headquarters, aides are just as excited about the Sanders surge. This was a hope. Now it’s their plan. If the next few weeks lead to the collapse of other leading campaigns—most crucially, Joe Biden’s, which is running short on money but occupying a similar ideological space as Bloomberg—and a Sanders-inspired freak-out, they believe the former New York City mayor will be the party’s nominee. Like many Democrats who aren’t supporting Sanders, they see a primary process that is setting up the party for a likely defeat.

“If Sanders soars through the first four primaries and Biden and [Pete Buttigieg] stumble, Mike may end up as the only thing standing between Bernie and the nomination.” That’s how Bradley Tusk, who managed Bloomberg’s 2009 mayoral campaign and is advising the presidential run, put it to me on Thursday. Sanders might run away with it, but “a large portion of the party believes that Bernie can’t beat Trump—and that beating Trump is all that matters.”

And so the prospect of a contested convention—in which the Democrats don’t have a presumptive nominee by the time they gather in Milwaukee in mid-July—is more likely than ever.

Even before the past few weeks of surging polls, Sanders aides were counting on winning about 1,500 delegates, short of the 1,990 they’d need to secure the nomination. The primary contest is an often-arcane state-by-state, district-by-district process, a system that makes even the Electoral College seem streamlined. Bloomberg is mounting a hard run at delegates himself. The chances that any candidate clears that 1,990 threshold gets slimmer every week the race goes on.

And here’s where political math and Democratic National Committee rules get important. If a nominee isn’t picked on the first ballot, then superdelegates—about 750 elected officials, party elders, and activists—get to vote in a second round. Sanders aides believe that their only real chance of making him the nominee is winning the first ballot. They’ve started using the phrase significant plurality, and arguing that the superdelegates should give the nomination to whoever’s in the lead, but they’re nervous that this won’t happen. So although they’re looking to crush Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, they’re still hoping she’ll stay in the race long enough to win some delegates of her own, then not officially drop out so she can make a deal with Sanders and instruct her delegates to vote for him. (Candidates can keep hold of delegates only if they officially remain in the race.)

Larry Cohen, a Sanders ally who runs a group called Our Revolution, has been quietly talking about a fusion plan for months, keeping in touch with the Working Families Party, which has backed Warren. This effort helped lead to a joint statement from a collection of major progressive groups, including Our Revolution and Working Families, pleading for solidarity for the sake of “a unified convention strategy.” Conversations about that strategy are not happening between the campaigns directly, though Sanders aides do like to chatter about the speculation. Warren’s plan for winning the nomination is to head into the convention with a delegate lead herself.

Biden, for his part, is predicting a long campaign of racking up delegates, though few believe this will be easy if he suffers a series of early losses. Frustration with Bloomberg, whose entire campaign is predicated on Biden’s supposed weakness, is intensifying in the former vice president’s campaign. "The answer to one Republican New York billionaire is surely not going to be a slightly richer Republican New York billionaire,” one Biden ally told me over the weekend. “It's laughable we even have to say that out loud.” Other Democrats are also openly uncomfortable with Bloomberg’s candidacy. After a campaign event in Iowa City on Saturday afternoon, Warren called Bloomberg’s self-funding, skipping-early-states approach “dangerous for our democracy.”

Bloomberg’s focus is indeed on the 14 states that will vote on March 3, Super Tuesday. He’s already heavily investing in states after that, too. He’s spent hundreds of millions of dollars on TV ads and on-the-ground organizing, quickly assembling an enormous operation. Last Sunday in Miami, one event at a synagogue in the suburbs featured a table of aides throwing free T-shirts to people as they milled around trays of cookies. Another event, at an art space in the Wynwood neighborhood, included a six-piece band and waiters holding trays of red and white wine in cups. The Bloomberg Borg has assimilated dozens of campaign staffers from failed campaigns. He probably spent more on that afternoon in Miami than some of those candidates spent on their whole campaign. Close to 1,400 voters showed up, took their cones of free french fries, put on a campaign button, and happily gave Bloomberg their contact information.

“We don’t think about this as taking away delegates. We’re looking at the electorate that needs to be mobilized now and also in the fall. We’re looking at the widest section of the Democratic electorate and what can unite the biggest chunk of it around a candidate and a message,” the campaign’s state-operations director, Dan Kanninen, told me on Friday, pushing back against the speculation about the convention as premature. He refused to engage in several of my attempts to goad him into taking on Sanders specifically. “I think Mike Bloomberg can win the coalition in both the primary and the general to beat Donald Trump, and he’s the only candidate who can do it."

In a month, all the outsize attention that candidates and reporters have been paying to early states will have dissipated, and most of the delegates will still be up for grabs. Bloomberg has an almost incomprehensible amount of money, enough to keep advertising and organizing and racking up delegates for months without making a dent in his fortune. If this does become a long nomination fight, he has the ability to make his case to superdelegates that the party is already behind in fighting Trump. And he’ll happily write checks to state parties and all sorts of other Democratic groups, the way he did when he was mayor of New York (although then, it was Republicans he wanted to win over).

Think about the chaos of a contested convention, with delegates sprinting around making deals, chased by reporters who will invoke Chicago 1968 at every possible opportunity.

A second ballot would be a “disaster,” Cohen told me. He led the Sanders-backed efforts after the last election to get rid of superdelegates entirely. Leaving them with any kind of role was a compromise, at best a technicality—the idea was that they’d give a numerical boost to whoever already led in pledged delegates. The thought that superdelegates could cost Sanders the nomination is upsetting enough for his supporters. The thought that he could lose to the man who shut down Occupy Wall Street with a dead-of-night police raid and has been nonchalantly spending his way into the Democratic process … it’s just too much.

“The notion that the 750 people who were not elected as delegates are going to come in after the country votes, and 18 months of campaigning and gigantic amounts of volunteer time—it’s really critical for our credibility that we have this first ballot,” Cohen told me, arguing that a contested convention would weaken the party’s ability to beat Trump.

If the Bloomberg plan is to take the nomination via any tactic but winning the most delegates and coming out ahead in the first round, “shame on them,” Cohen said. “It makes a mockery of it all.”

Sanders and Bloomberg each symbolize something much bigger than themselves. They’ve each promised to support the eventual Democratic nominee—Sanders insists that the prospect of another Trump win is more important than ideological differences between Democrats, and Bloomberg has pledged to keep his billion-dollar operation going whether he wins or not. But would Bloomberg really keep his fortune pumping to help elect a socialist, especially after losing at the convention? And would Sanders really back a billionaire moderate who got party insiders to throw him the nomination?

“There are going to be a lot of people who are going to be very upset if they feel like the election was stolen from them by a cabal of corporate types,” Jeff Weaver, Sanders’s top strategist and generally the most reliable reflection of the senator’s thinking, told me a few weeks ago.

Comments like this make me think of the day in Philadelphia in 2016 when Hillary Clinton was officially nominated and dozens of Sanders supporters staged a walkout. Some were holding Sanders signs. Some had put Sanders campaign stickers over their mouths, to show that they’d been silenced. That was after Sanders had given a speech urging his supporters to unify behind Clinton. But people who were there that afternoon told me they felt like they had to keep up the fight, even without the candidate. Enough Sanders supporters remained so disenchanted that they stayed home on Election Day, or voted for Jill Stein or Trump. Even some of Clinton’s most devoted supporters have admitted privately that they’d be uncomfortable with Bloomberg grabbing the nomination from Sanders. The risk of fracture within the party seems enormous.

Phil Levine, the former mayor of Miami Beach, told me after Bloomberg’s event in Wynwood that he wasn’t concerned about a blowup. The goal of beating Trump can create its own unity, he argued, and Democrats have to be realistic about the fact that Trump won in 2016. “What makes us think they want to elect a socialist?”

“Promising to spend trillions of dollars of taxpayer money just to get yourself elected is buying an election,” Tusk, the Bloomberg adviser, told me. “Using money you earned to run a campaign that does not need or take money from any outside interest is laudable.”

Of course, maybe Biden ends up in a stronger position, or Warren rebounds, or Buttigieg runs strong. Or maybe Andrew Yang or Tom Steyer rack up enough delegates to play kingmaker themselves.

For now, Democrats watching from the sidelines are worried. But, as one former staffer for a candidate no longer in the Democratic race texted me, the Republicans must be having a blast.