Impeachment Hurt Somebody. It Wasn’t Trump.

In the end, the president succeeded in doing precisely what he wanted in the first place: tarring a leading Democratic rival.

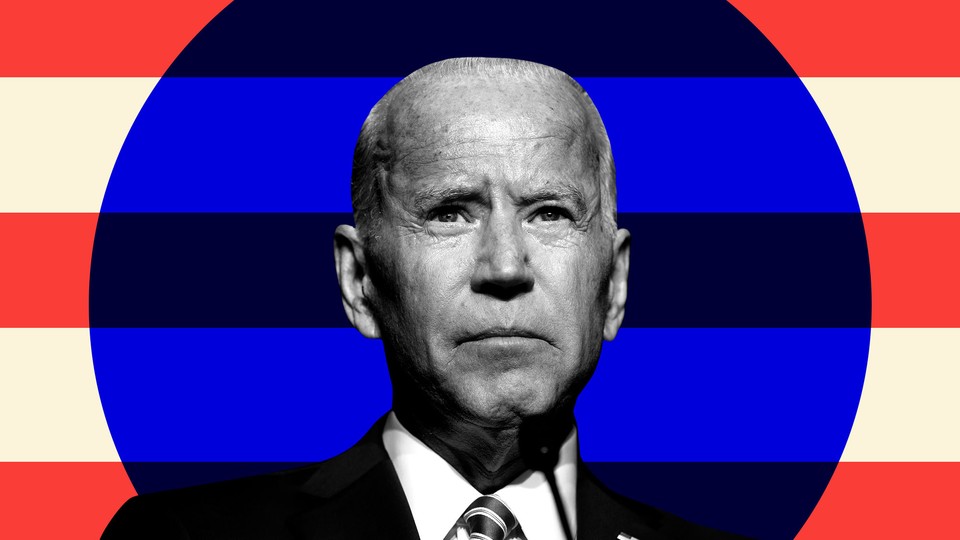

The impeachment struggle is now over. Historians may one day vindicate Democrats for exposing Donald Trump’s abuse of power. But as of now, they have lost. Not only will Trump remain president, and not only does he appear stronger politically than before the impeachment battle began, but he has succeeded in doing precisely what he wanted in the first place: He tarred Joe Biden, who last year looked like Trump’s most formidable Democratic rival, with the kind of vague suspicion of wrongdoing that presidential candidates can’t easily shake.

When Trump called Volodymyr Zelensky on July 25, he was trying to pressure the Ukrainian president into investigating Biden. Biden’s son Hunter had served on the board of Burisma Holdings, a Ukrainian gas company. Trump saw an opportunity to create an aura of corruption around the former vice president and threatened to withhold military aid to Ukraine unless Zelensky announced an investigation. Whether the investigation occurred or not was immaterial; Trump just wanted the announcement. But when a U.S. government staffer exposed the call, Trump was forced to release the aid—and the impeachment drive began.

Yet, ironically, the impeachment effort and the Republican counterattack against it have largely accomplished Trump’s goal. By keeping Hunter Biden’s business dealings in Ukraine in the news, they have turned them into a rough analogue to Hillary Clinton’s missing emails in 2016—a pseudo-scandal that undermines a leading Democratic candidate’s reputation for honesty. The Trump campaign and the Republican National Committee last fall launched a $10 million advertising blitz aimed at convincing Americans that Joe Biden’s behavior toward Ukraine was corrupt. After Trump’s lawyers devoted much of their energy in the Senate impeachment trial to demanding that Biden be investigated for corruption, Republican Senator John Barrasso of Wyoming crowed that the attacks would be politically “harmful” to the former vice president “in November if he’s the nominee and I think even in terms of getting the nomination.”

Barrasso was right. Although Trump and his allies have proved no wrongdoing, the Ukraine story, according to an October Investor’s Business Daily poll, made 23 percent of Americans less likely to vote for Biden, and only 8 percent more likely to vote for him. A Hill-HarrisX poll that same month found that 54 percent of independents—and even 40 percent of Democrats—considered “Hunter Biden’s business dealings in Ukraine an important campaign issue that should be discussed.”

Biden’s extremely defensive response to the story has made matters worse. When a Fox News reporter asked the former vice president about his son’s work in Ukraine in September, Biden lectured, “Ask the right question.” In December, after Biden called an Iowa man a “damn liar” for raising the issue, Politico noted, “Biden has two methods of responding to questions about his son’s controversial business dealings in Ukraine: denial and anger. But so far, Biden doesn’t have a clear and cogent message—and Iowa voters are starting to take notice.” On caucus day itself, when NBC’s Savannah Guthrie asked about Hunter’s work in Ukraine, Biden snapped, “You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

Biden has plenty of other weaknesses. But the Ukraine story is likely one reason that, according to a January Quinnipiac poll, he trails Bernie Sanders by nine points on the question of which Democratic presidential candidate is most honest. Since entering the race, Biden has generally performed better than his leading rivals in head-to-head polls against Donald Trump. But there’s evidence that over the course of last year, the pre-impeachment advantage Biden enjoyed in key swing states eroded.

Amazingly, impeachment appears to have hurt Biden more than Trump. Since House Speaker Nancy Pelosi initiated the impeachment inquiry on September 24, Trump’s approval rating has generally risen. It stood at 40 percent in the first Gallup poll after Pelosi’s announcement. In Gallup’s latest survey, Trump stands at 49 percent. According to RealClearPolitics’ polling average, Trump’s rating dropped a bit during the first month of the impeachment fight but has climbed ever since, and is now almost 45 percent—nearly as high as it has been during his entire presidency. As Aaron Blake has pointed out in The Washington Post, Trump has also seen a spike in the intensity of his support, while the intensity of public opposition has declined. Since late October, according to a recent Washington Post–ABC News poll, the percentage of Americans who strongly approve of Trump’s job performance has jumped five points, while the percentage who strongly disapprove has fallen eight points.

This spike in intensity is also reflected in fundraising. The Democratic National Committee raised roughly the same amount in May through August—the four months preceding the impeachment inquiry—as it did in September through December. (Figures are not yet available for January.) The Republican National Committee’s haul, meanwhile, grew during that span by almost $25 million. Combine the RNC’s fundraising with the Trump reelection campaign’s fundraising, and you see similar post-impeachment growth: from $105 million in the second quarter of 2019 to $125 million in the third quarter—when the impeachment inquiry began—to $154 million in the fourth quarter, during which the House voted to impeach. The leading Democratic presidential candidates, by contrast—with the exception of Sanders—did not see consistent fundraising growth during that period. Pete Buttigieg raised more money in the second quarter, before the impeachment inquiry began, than he did in the third quarter, once it got under way. So did Joe Biden. Elizabeth Warren saw her fundraising dip in the fourth quarter, as the House impeachment inquiry reached its climax.

Nancy Pelosi may have foreseen this outcome. Last March, she said Democrats should avoid impeachment “unless there’s something so compelling and overwhelming and bipartisan” that it couldn’t be ignored. But her criteria conflated evidentiary standards with political ones. The case for impeaching Trump over Ukraine has proved “compelling and overwhelming.” But it has not proved “bipartisan,” because congressional Republicans care less about weighing evidence than displaying their allegiance to Trump.

Pelosi and her fellow Democrats have behaved honorably. Politically, however, they are facing the very backlash that she feared a partisan impeachment might spark. They have energized Trump’s supporters without similarly energizing their own. The backlash isn’t nearly as widespread as Republicans faced when they tried to impeach Bill Clinton. But given how desperately Democrats want Trump to lose—and how small a margin of victory they have—this backlash is frightening enough. And Joe Biden may be its first victim.