Why West Side Story Abandoned Its Queer Narrative

A new revival shows that the musical is still bound by ethnic stereotypes, and that it would work best by returning to its origins.

Shortly before West Side Story opened on Broadway in the fall of 1957, the lyricist Stephen Sondheim received an angry letter from a doctor. One of the musical’s standout numbers in its Washington, D.C., tryout had been “America,” a playful debate between Rosalia, who longs to return to Puerto Rico, the “island of tropical breezes,” and Anita, a stateside enthusiast who mocks Rosalia’s nostalgia for an “island of tropic diseases.” As Sondheim recalled in his annotated collection of lyrics, Finishing the Hat, Dr. Howard Rusk, the founder of a New York medical center, complained that the song misrepresented Puerto Rico, which had, in fact, a very low instance of tropic diseases and a lower mortality rate than the continental United States. “I’m sure his outrage was justified,” Sondheim conceded, “but I wasn’t about to sacrifice the line that sets the tone for the whole lyric.” Although editors from New York’s Spanish-language newspaper La Prensa threatened to picket West Side Story for portraying Puerto Ricans as a public-health threat, and Rusk wrote an article for The New York Times headlined “The Facts Don’t Rhyme,” the show proceeded with Anita’s jab intact.

More than 60 years later, the latest revival has opened on Broadway amid urgent debates about Puerto Rico’s relationship to the U.S., renewing questions about the tension between rhyme and facts, between artistic coherence and authentic representation. While West Side Story’s feuding, leaping, singing Sharks and Jets have long been lauded for lofting musical theater to the lyrical heights of Shakespearean tragedy, the show has also been criticized for promoting stereotypes of Puerto Ricans in the states as exoticized, eroticized gangbangers. Those stereotypes were popularized by the 1961 film, in which the only Puerto Rican star in the cast, Rita Moreno (who won an Oscar for playing Anita), was forced to darken her skin with brown makeup: a caricatured, cosmetic distortion of Puerto Rican identity. (A remake of the film, directed by Steven Spielberg, is set to be released in December.)

“I think West Side Story for the Latino community has been our greatest blessing and our greatest curse,” Lin-Manuel Miranda told The Washington Post in 2009. Miranda was cast as Bernardo, the Sharks’ leader, in a sixth-grade performance, and was thrilled, as a Nuyorican who spent summers on the island, to see the question of whether to return to Puerto Rico staged in “America.” He directed West Side Story at his high school in 1998, bringing in his dad to teach his Upper East Side classmates how to act Latino. That same year, Paul Simon’s short-lived musical The Capeman ran on Broadway, dramatizing the mid-century story of a Puerto Rican teenager convicted of stabbing a white boy to death. “It was us as gang members in the ’50s, again,” Miranda explained to Grantland. “We should be able to be onstage without a knife in our hand. Once.” In college, Miranda wrote his own musical, In the Heights, which celebrated the daily struggles of Puerto Rican, Cuban, and Dominican New Yorkers—no knives involved. It became a 2008 Tony-winning hit, and Sondheim and Arthur Laurents, who wrote the script for West Side Story, hired him to translate some of the Sharks’ lyrics into Spanish for the previous Broadway revival, in 2009.

The Belgian director Ivo van Hove, known for his radical revisions of American classics—stripped-down, often brutally violent stagings with dynamic video projections—thought he could create a West Side Story that represents America today. He told me that he got the idea for his production during Donald Trump’s presidential campaign and the rise of Black Lives Matter. “I thought, There’s a story that has been telling these things about America, an America that we had forgotten that it still existed.” He picked up the script of West Side Story, which he’d seen on television as a teenager in Flanders, and was amazed that its dialogue about rival gangs still spoke to the present. “It touches on poverty, it touches on racism, it touches on prejudice, it touches on violence,” van Hove said. He proposed a new vision of the show to the producer Scott Rudin: “a West Side Story for the 21st century.”

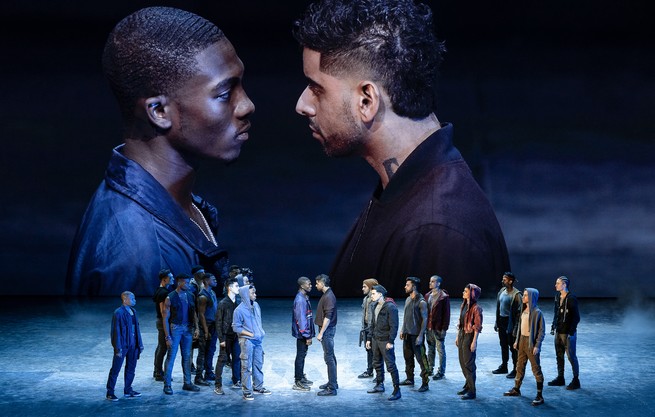

There’s no mistaking van Hove’s version for the one you grew up with. Instead of brownface, the Sharks reflect the youthful diversity of Latinidad, tattooed with the word tiburón (Spanish for “shark”). Instead of all-white American boys in high-waisted pants, the Jets include black men and women in sweats, hoodies, and sports bras. There’s no more finger-snapping ballet; instead of Jerome Robbins’s original choreography, van Hove tapped Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker—known for angular moves that Beyoncé lifted for her “Countdown” music video—to channel hip-hop and club styles. (At the cast’s request, De Keersmaeker told me, Latinx choreographers were also hired to make the Sharks’ dances more authentic.)

Isaac Powell’s Tony looks fresh and rough, with a scar on his cheek and “Jets for Life” tattooed on his neck. Shereen Pimentel’s Maria is powerful and ardent, no dainty ingenue. Perhaps most striking, there’s no visible set, just an exposed stage painted black with giant video projections along the back wall—now a close-up on Tony’s face; now a scene in Maria’s bedroom, performed offstage; now an extension of the deserted street where the gangs roam; now a shot of a white police officer pointing a gun at an unarmed black man.

You won’t hear tropic diseases in this production; van Hove, intent on bringing out the musical’s contemporary politics, chose lyrics from the film version of “America,” which pits Anita’s disdain for Puerto Rico against Bernardo’s experience of American racism. (“Life is all right in America.” “If you’re all-white in America.”) When Anita disparages her birth island—“always the hurricanes blowing, always the population growing”—the audience sees news footage of Hurricane Maria devastating San Juan. At the end of the song, a long aerial tracking shot shows the border wall with Mexico. “It’s the sociological story, the political dimension of the story that interests me most,” van Hove said.

And that’s where the challenge comes in. Grafting sociological precision onto a musical that, from its start, traded facts for rhyme is tough. Unlike Mexico, of course, Puerto Rico isn’t separated from the U.S. by a border wall; Puerto Ricans have been U.S. citizens since 1917. When van Hove defended his choice to add more instances of the insult spic to his script, he told me that it is a motif that runs throughout the show: “It’s the insult they use for Mexicans; it’s the word that makes Bernardo explode.” Was he confusing Mexicans with the show’s Puerto Rican characters? Or was he making a case for a pan-Latinx experience of migration and discrimination? The problem with treating the musical’s stylized representations as documentary realism is that it presents ethnic caricatures as news footage.

When van Hove leans into West Side Story’s purported sociology, he leaves you feeling a little American Dirt-y: You’re being served up sensationalized Latinx stereotypes as though they were dispatches from the border. As the Sharks sing, “Immigrant goes to America,” the Broadway Theatre back wall displays video footage of Mexican immigrants splashing across the Rio Grande. True, some immigrants do get to the United States that way; West Side Story is capacious enough to resonate in many cultural contexts. But to accept the musical as an account of contemporary migrant trauma is to verge on parody. West Side Story has always been about what it means to become American. But it’s never really been about what it means to be Puerto Rican. As a Latinx musical, West Side Story is incoherent and insulting. As the mid-century fantasy of queer Jewish artists, however, it’s surprisingly compelling.

T

he musical’s origin story is one of displaced ethnicity. When Robbins first approached Laurents and the composer Leonard Bernstein in 1949 with an idea for a modern Romeo and Juliet, he proposed Jews and Catholics sparring during the week of Passover and Easter on New York’s Lower East Side. (Early newspaper accounts of their collaboration referred to the project as East Side Story.) They drafted an outline: When the Jewish Dorrie runs into the Catholic Tonio at a Mulberry Street dance festival, her Tante—her Yiddish-speaking aunt—calls Tonio a “shane boychick” (a good-looking young man), but Dorrie’s brother Bernard tells her to “stick to our side of the street,” by the kosher store and Stronsky’s Bridal Shoppe. The seeds of West Side Story were there—the street festival became the dance at the gym; Tonio became Tony; Dorrie became Maria; Bernard became Bernardo; Tante became Anita; Stronsky’s Bridal Shoppe became the Puerto Rican bridal shop; and “stick to our side of the street” became “stick to your own kind,” Anita’s refrain to Maria in “A Boy Like That.” But how did Yiddish become Spanish?

It’s complicated. Robbins, born Jerome Rabinowitz, was deeply conflicted about his Jewish roots and terrified at being outed as gay by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Laurents, born Arthur Levine, was blacklisted during the Joseph McCarthy hearings. Even on the left, as “a Jew and a homosexual, I was, of course, an outsider, if not a pariah, no matter what my achievements,” Laurents wrote in his memoir. That sense of alienation may have shaped his response to Robbins’s initial idea; a sentimental play from the 1920s called Abie’s Irish Rose was about Jewish-Catholic intermarriage and assimilation, and Laurents complained that East Side Story would just be Abie’s Irish Rose set to music.

The project stalled for a few years until Laurents ran into Bernstein in Beverly Hills and they noticed a headline in the newspaper: “More Mayhem From Chicano Gangs.” Bernstein, who had written his Harvard thesis on “the absorption of race elements into American music,” began to hear a Latin score. Laurents said he didn’t know any Chicanos, so he suggested shifting the story to the Upper West Side, where cases of juvenile delinquency were being reported, and where Puerto Rican migration was rapidly increasing. “New York and Harlem I knew firsthand,” he wrote, “and Puerto Ricans and Negroes and immigrants who had become Americans.” Laurents’s script defined the change: “The Sharks are Puerto Ricans, the Jets an anthology of what is called ‘American.’” They invited Sondheim, an untested young writer from Westchester, to write lyrics with a youthful feel. “I can’t do this show,” he responded. “I’ve never been that poor and I’ve never even known a Puerto Rican!” But, as Sondheim explained to me in an email, the creators “were much less concerned with the sociological aspects of the story than with the theatrical ones. The ethnic warfare was merely a vehicle to tell the Romeo and Juliet story ... It might just as well have been the Hatfields and the McCoys.”

Robbins wanted to choreograph a street ballet; Bernstein wanted to compose an American opera; Laurents wanted to write a topical drama; Sondheim just wanted a job. These four queer Jewish artists created a thrilling musical about love thwarted by prejudice, sustained by the hope (in the lyrics from “Somewhere”) that “there’s a place for us.” In the film, when Moreno’s Anita asks the Jets to “let me pass,” and they reply, “You’re too dark to pass,” a long, deeply lived history of anxiety about Jewish assimilation, closeted sexuality, and the McCarthy blacklist gets displaced, cosmetically, onto a stereotyped construction of Puerto Rican femininity. And when Anita dreams of getting her own apartment, and George Chakiris’s brownface Bernardo retorts, “Bedder get reed of your ahccent,” the layers of ethnic performance are so thick, it’s hard to remember what’s underneath.

The van Hove revival leans so heavily on the spectacle of brown suffering that the show’s origins are almost effaced. That’s particularly palpable in the director’s choice to cut “I Feel Pretty,” Maria’s only featured number (with the other Puerto Rican women in chorus), and as pure an expression of queer joy as Sondheim and Bernstein wrote. Van Hove wanted to trim the show’s running time and sustain the momentum of the tragic plot, which “I Feel Pretty” certainly interrupts. And he claimed authority from Sondheim, who always regretted the song. The reasons Sondheim distanced himself from his own composition, though, are also tricky. Sondheim said another lyricist, Sheldon Harnick, suggested to him that “lines like ‘It’s alarming how charming I feel,’ words like ‘stunning,’ and phrases like ‘an advanced state of shock’ might not belong in the mouths of Maria and her friends.” What sounds like a slight of Puerto Rican women’s capacity for cleverness, though, might also reflect Sondheim’s discomfort with feeling that he had revealed too much of himself in lines such as “I feel pretty and witty and gay” and “I’m in love with a pretty wonderful boy.” He wrote in Finishing the Hat that he knew his wordplay “drew attention to the lyric writer rather than the character,” but he “hoped no one would notice.” Without the song, West Side Story is swifter, but a little less pretty and witty and gay; the cut also reduces Maria’s and her friends’ capacity for celebration and self-expression, shifting the focus to the male gang leaders.

If you’re tempted to cast West Side Story as a world in which male bonds override female agency, the casting of Amar Ramasar as Bernardo doesn’t dispel that thought. Rudin and van Hove gave the role to Ramasar, a dancer who was accused of sharing sexually explicit photos of female dancers and subsequently fired from the New York City Ballet in 2018 for having “engaged in inappropriate communications, that while personal, off-hours and off-site, had violated the norms of conduct.” (He was reinstated seven months later after an arbiter ruled that suspension, rather than termination, was the appropriate punishment.) At the time, Ramasar was also starring in Rudin’s production of Carousel on Broadway; his understudy replaced him for one performance after the sexual-misconduct allegations became public in a lawsuit, and then he returned to the cast. Protesters organized an online petition objecting to Ramasar’s casting in West Side Story, and some have gathered nightly outside the Broadway Theatre, holding signs that read Boo Bernardo. When I asked van Hove to comment, he told me that before Ramasar was cast, he had been “acquitted,” which isn’t quite accurate; Rudin clarified on 60 Minutes that there had been “no firing offense.” “I don’t excuse it,” Rudin continued. “I think what he did was really stupid. I mean, am I supposed to replace him in the show? I’m not going to do that.”

For a show long charged with representing Latino men as predators, casting Ramasar hardly helps. Even more concerning, however, may be the tradition of West Side Story treating the sexual exploitation of women’s bodies as the condition for artistic achievement. The change Laurents was most proud of, as he adapted Romeo and Juliet for New York gangs, came in the ending: Instead of a coincidental plague stopping the message about Juliet’s fake suicide from reaching Romeo in time, Laurents thought that prejudice had to be the cause of the story’s tragedy. And so he added a racially motivated sexual assault. When Anita tries to reach Tony to tell him that Maria is waiting for him, the Jets block her way (“You’re too dark to pass”). Then they try to rape her. Escaping, enraged, Anita shouts at them to tell Tony that Maria is dead. Hatred has conquered love. Laurents frequently boasted that the scene was “an improvement on Shakespeare.”

In some productions, the attempted rape is staged indirectly. But in the new Broadway revival, van Hove, who has a history of staging graphic sexual violence, directs the scene as an explicit sexual assault, visible onstage and projected in an extreme camera close-up. “It’s the ultimate violation, the ultimate insult, the ultimate degrading,” he told me. “That’s what I do here. I really wanted to go at the edge of the situation because otherwise I felt I was betraying Anita.” He assured me that the scene had been carefully choreographed with a fight director and an intimacy director, and that the actor playing Anita, Yesenia Ayala, had consented to each choice. (The production did not grant my request to interview Ayala.) But the inclusion of the scene—as well as Ramasar’s presence in the cast—sends a message that women’s bodies are collateral damage in male artistic success, from Laurents’s “improvement” to Ramasar’s casting, and van Hove’s “ultimate” achievement.

When van Hove and De Keersmaeker depart from brutal realism and let in a touch of queer fantasy, West Side Story takes flight. After the gangs’ tension erupts in the show’s climactic rumble scene, with bodies lying dead or battered across the stage, the aching strains of “Somewhere” begin. And somehow, those bodies float up and begin to couple—he and him, she and her, they and them. Arms and legs intertwine in urgent need, a dance of rapture amid death. Then you can see the musical’s displaced longing without the distortion of ethnic appropriation. For a fleeting moment, onstage, there’s “a place for us”—a place, in the late Seamus Heaney’s phrasing, where hope and history rhyme.