After Social Distancing, a Strange Purgatory Awaits

Life right now feels very odd. And it will feel odd for months—and even years—to come.

Defying all medical advice, and ignoring the nature of viral infections, President Donald Trump wants to see “a very powerful reopening plan” by May 1. Two groups of governors—one in the West Coast states and another in the Northeast—are vowing to coordinate efforts to ease social distancing, if not on Trump’s terms then on their own. Still, in a recent statement, California Governor Gavin Newsom, a member of the West Coast group, listed a variety of medical and health benchmarks for ending the lockdown, none of which seems likely to be met very soon. He admitted as much, warning we shouldn’t get “ahead of ourselves.”

Anyway, most of the decisions that matter aren’t in the hands of presidents or governors; American society as a whole needs a plan for what comes next. The coronavirus is revolutionary not just because of the suffering it has caused, but because it—like other diseases, from the bubonic plague to malaria to HIV—has the power to shape social norms for years to come. Those norms change with surprising speed. For most people, the prospect of sitting at home for months was almost unthinkable at the beginning of March.

Over the past week, I’ve been informally contacting friends and colleagues in a variety of fields—sports, travel, architecture, entertainment, arts, the clergy, and more—to ask them how their world might look after social distancing. The answer: It looks weird.

We will get used to seeing temperature-screening stations at public venues. If America’s testing capacity improves and results come back quickly, don’t be surprised to see nose swabs at airports. Airlines may contemplate whether flights can be reserved for different groups of passengers—either high- or low-risk. Mass-transit systems will set new rules; don’t be surprised if they mandate masks too.

Changes like these are only the beginning. After most disasters, recovery occurs days or weeks or a few months later—when the hurricane has ended, the flooding has subsided, or the earth has stopped shaking. Once the immediate threat has abated, a community gets its bearings, buries its dead, and begins to clear the debris. In crisis-management lingo, the response phase gives way to the recovery stage, in which a society goes back to normal. But the coronavirus crisis will follow a different trajectory.

Until scientists discover a vaccine, doctors develop significantly better medical treatments, or both, people all over the world will be working around, sharing space with, and sheltering from a virus that still kills. The year or years that follow the lifting of stay-at-home orders won’t be true recovery but something better understood as adaptive recovery, in which we learn to live with the virus even as we root for medical progress.

During this strange purgatory, places such as schools will be governed by direct orders from public officials, and large corporate employers will have tremendous influence on work-related norms. But Americans spend a good amount of our life and money in other spaces. After basic needs are addressed or met, what will it be like to be you?

Face shields—not masks, but clear plastic full-face shields—will be required for fans at sports games or concerts, to the extent that those happen at all. Golf could become the sport of choice as it’s easy to maintain distance and is outdoors. Not coincidentally, the PGA Tour announced plans this week to restart its season in June.

In some of the rosier scenarios, COVID-19 testing and tracking become widespread enough that most businesses can stay open. Even then, the very idea of having a routine—picking up or dropping off dry cleaning on your own schedule—will be lost as individual businesses open or close based on the health of employees. Communal experiences—including the arts and performances and programs such as book events—will no longer exist without much more stringent health protocols. Pre-ticketed admissions may become the norm at museums or movie theaters; as for the latter, The New York Post recently reported that the movie chain AMC, which had to close all its movie houses, is talking to bankruptcy lawyers. The company disputes such reports, but its financial situation, like that of other cinema companies, is daunting.

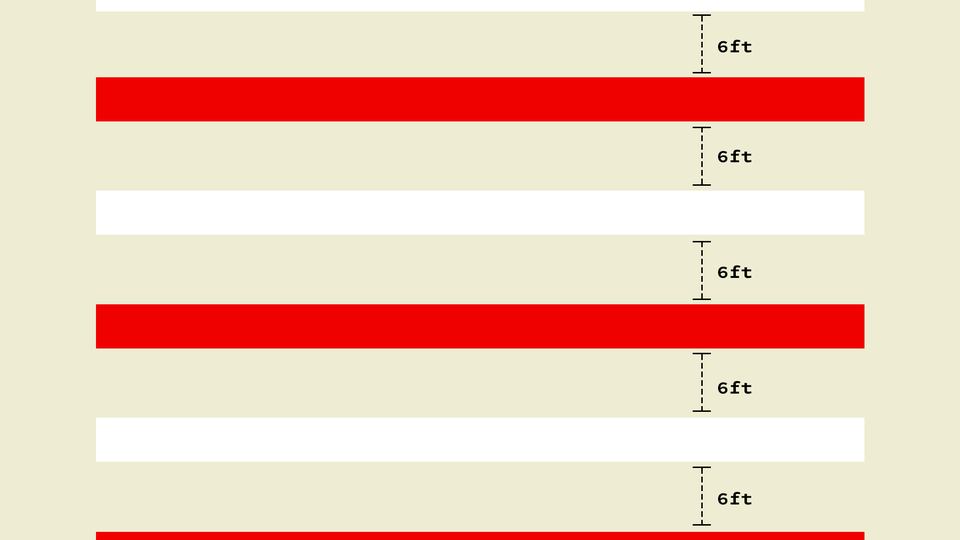

We will choose our social events wisely. To lure you in, restaurants will mandate temperature screening and reduce the number of tables so that patrons don’t feel crowded in. Servers will wear protective equipment; menus will be disposable. The maximum capacity of bars will be cut in half, if not more; since the Cocoanut Grove era, the number of people allowed in such establishments has been constrained by fire codes, but a fast-spreading coronavirus dictates even more space per person. As stores restrict admission at peak times and long lines form outside, we may find ourselves scheduling appointments to buy groceries.

Some of these protocols will garner widespread public support; others, like certain airport security measures after 9/11, will strike a jaded public as being merely for show. The changes will happen anyway. Cities will implement one-way sidewalks. Millennials who are starting families could begin a new exodus from tight urban quarters: The exurbs are the new Williamsburg!

New expressions of love, fellowship, and human connection will be tested. To visit a friend or relative who has just become a parent, we will not lightly jump on a plane—as middle-class Americans might previously have done in an age of relatively cheap flights. (But your new baby looks adorable on Zoom.) Responsible religious leaders will find alternatives to rituals—such as the “passing of the peace” in many Christian denominations and its equivalent in other faiths—that could spread germs. Expect a wave of memorial services as families belatedly mourn those who have perished from COVID-19 and other causes, but many people will hold back from forms of human contact—perhaps reflexively rather than intentionally—that once seemed second nature.

On dating apps, people will specify (with varying degrees of accuracy) whether they’ve had COVID-19. Casual making out will come to seem reckless. A handshake? Have those test results ready. A friendly hug? I don’t even know your last name.

Our attitudes and outlooks may change in disappointing ways. We will be home a lot more. We’ll also use shaming, against friends and others whom we judge to be taking needless risks, to cultivate better voluntary behavior.

The simplistic idea of “opening up” fails to acknowledge that individual Americans’ risk-and-reward calculus may have shifted dramatically in the past few weeks. Yes, I’d like to go meet some girlfriends for drinks. But I am also a mother with responsibilities to three kids, so is a Moscow mule worth it? The answer will depend on so many factors between my home and sitting at the bar, and none of them will be weighed casually.

Adaptive recovery is like living through evolution in real time. We will swerve and pivot, become acclimated to random closures and sudden changes in testing regimens, and hope that we can box the virus in long enough to buy time for a more permanent solution.

My friend Jonathan Walton, the dean of Wake Forest University’s School of Divinity, has described our time hiding from, mobilizing against, and then living with the virus as the “now normal,” the simple effort to live each day as if it were typical, knowing that the next day will bring a new round of uncertainty. Our reentry will be slow. There could be another wave. Adaptive recovery is going to last a very long time—and it will not feel normal at all.