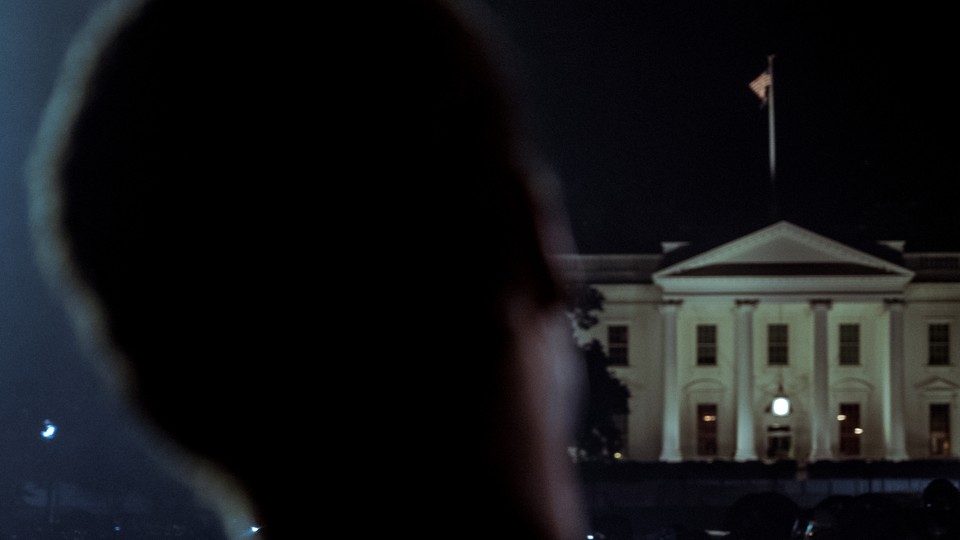

Last night, as protests convulsed Washington, D.C., the White House went dark. All the lights were off. The windows of the president’s official residence were darkened, and the floodlights outside extinguished.

The country is sick, angry, and divided, but it also finds itself leaderless. Trump has never shown any inclination or ability to soothe or console in moments of crisis. He wants the trappings of power, like showing up for a rocket launch, but he doesn’t want to get his hands dirty with the work of governing. And he continues to view himself as the president only of the minority who voted for him, not all Americans. These tendencies have converged in this moment.

Yesterday, when America needed real leadership, the office of the president stood dark—and vacant.

It is not that Trump has been silent. Far from it: His Twitter feed has been a supercharged version of its normal self. Trump has attacked Joe Biden, slurred reporters, insulted leaders on the front lines of protests, and claimed federal authority he doesn’t have. This is the sort of behavior we’d call unhinged from any other president, but the word has lost any power through its endless, justified invocation throughout his tenure. In any case, the tweeting suggests a president flailing around for a message that sticks and for a sense of control.

What has been missing is any sort of behavior traditionally associated with the presidency. Trump initially condemned George Floyd’s killing by a Minneapolis police officer, but since then there have been no statements intended to quell anger, bridge divisions, or heal wounds. There have been no public appearances, either; Trump traveled all the way to Florida to watch a SpaceX rocket launch on Saturday, but hasn’t managed to travel in front of cameras for a formal statement.

During a teleconference Monday, Trump derided governors as “weak” in their response to protests, but he has cowered out of view, dithering about what to do except for armchair-quarterbacking those who are trying. As my colleague Peter Nicholas notes, even Richard Nixon went to speak with anti–Vietnam War protesters in 1970, trying to convey that he heard their complaints. It’s hard to imagine Trump doing something like that, because he has shown no interest in being perceived as caring about what his critics believe.

As I noted in the closing days of the 2018 midterm race, the challenge of a democratic polity is that leaders must run on behalf of one party, then govern on behalf of everyone. In a one-party state, there’s no such divided polity, and that’s what Trump seems to prefer. His lack of interest in unifying Americans has been on display over the past few days.

Despite the vacuum that Trump’s silence creates, practically no one wants to hear from him. They know that he will only make the situation worse, whether by intention—“when the looting starts, the shooting starts”—or by clumsiness. People may yearn for a leader, but they don’t yearn for him.

“He should just stop talking. This is like Charlottesville all over again,” Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms said on CNN last night, referring to Trump’s disastrous comments after a violent white-nationalist march in Virginia in 2017. “He speaks and he makes it worse. There are times when you should just be quiet, and I wish that he would just be quiet.”

It isn’t just Democratic leaders like Bottoms who are saying that. His own aides agree. They wish he’d stop tweeting, and while there are sporadic calls for Trump to make an Oval Office address, the prevailing view among his advisers—led by his son-in-law, Jared Kushner—is that such an address would be unwise. These staffers remember that Trump’s March Oval Office address on the coronavirus was full of errors and a political loser. Like Bottoms, they see a parallel with Charlottesville and worry that Trump will just make things worse.

They’re almost certainly right. Trump is unable to analyze any issue outside the lens of electoral politics—or, more precisely, his own political fortunes. When The New York Times asked Trump yesterday what he was going to do to address unrest, he replied, “I’m going to win the election easily … The economy is going to start to get good and then great, better than ever before. I’m getting more judges appointed by the week, including two Supreme Court justices, and I’ll have close to 300 judges by the end of the year.”

If Trump’s goal is to maximize his political advantage in this moment, he could demonstrate leadership in ways other than giving a speech. As Adam Nagourney points out, a well-timed appearance like Bill Clinton’s visit to riot-stricken Los Angeles in 1992 can help make a campaign. Some Trump aides are reportedly encouraging listening sessions, although no one who’s watched Trump in action can possibly imagine him earnestly listening and learning, or getting through such an exercise without a gaffe. (Biden, Trump’s presumptive Democratic opponent, has also been notably quiet, only cautiously venturing out of isolation in his house in Wilmington, Delaware, yesterday.)

Nothing in Trump’s statement to the Times touches the demonstrations or shows even a rudimentary understanding of what has inspired them. The paper reports that “aides repeatedly have tried to explain to him that the protests were not only about him, but about broader, systemic issues related to race.” Unsurprisingly, Trump, who has a long history of racist behavior and comments, has not warmed to that explanation. Instead, he has gravitated toward conspiracy theories. Yesterday, he tweeted that he would designate antifa—a familiar rhetorical target—as a terrorist organization, even though he has no federal authority to do so. He also blamed outside agitators for unrest, a claim debunked by his own allies at National Review. It seems true that there are some violent protesters trying to stir up trouble, but they are plainly neither the starting point nor the majority of the marchers.

In short, Trump has no plan to reach out to anyone who doesn’t already agree with him about antifa, he has no notions about how to pacify the protests, and he’s in denial about what is causing them.

He may also be in denial about his electoral prospects. The case that the protests help Trump is simple enough—voters see chaos and gravitate toward a strongman over a warm, fuzzy liberal. But it’s hard to run credibly as a law-and-order candidate when your four years in the presidency have seen repeated chaos, violence, and disorder, from Charlottesville to Pittsburgh, El Paso to Dayton, Parkland to Minneapolis. Nixon was able to use that playbook in 1968, but he was running as an outsider, not as the incumbent.

Nonetheless, the election was at the top of Trump’s mind on Monday morning. He delivered an incoherent anti-Biden message and tweeted triumphantly about a new ABC News/Washington Post poll, surely the first time a sitting president has boasted about a poll showing him trailing by 10 points. Another tweet was odder still:

NOVEMBER 3RD.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 1, 2020

That date is Election Day, of course. Trump presumably means it as a rallying cry for his supporters, but it is a reminder to those he doesn’t bother to represent, too—of their chance to fill the vacant office of the president.