A Devastating New Stage of the Pandemic

The U.S. has seen more cases in the past week than in any week since the pandemic began.

Updated at 9:30 a.m. ET on June 26, 2020.

For the past few weeks in the United States, the awful logic of the coronavirus seemed to have lifted. Stores and restaurants reopened. Protesters flocked to the streets. Some people resumed going about their daily lives, and while many wore face masks, many others did not.

Yet cases continued to ebb. Even though the U.S. had adopted neither the stringent lockdowns nor the trace-and-isolate strategies seen in other countries, its number of confirmed COVID-19 cases settled into a slow decline. Last week, Vice President Mike Pence bragged that the country had made “great progress” against the disease, highlighting that the average number of new cases each day had dropped to 25,000 in May, and 20,000 so far in June.

That holiday has now ended. Yesterday, the U.S. reported 38,672 new cases of the coronavirus, the highest daily total so far. Ignore any attempt to explain away what is happening: The American coronavirus pandemic is once again at risk of spinning out of control. A new and brutal stage now menaces the Sun Belt states, whose residents face a nearly unbroken chain of outbreaks stretching from South Carolina to California. Across the South and large parts of the West, cases are soaring, hospitalizations are spiking, and a greater portion of tests is coming back positive.

The country’s second surge has arrived—and it is hammering states, such as Texas and Arizona, that escaped the first surge mostly unscathed.

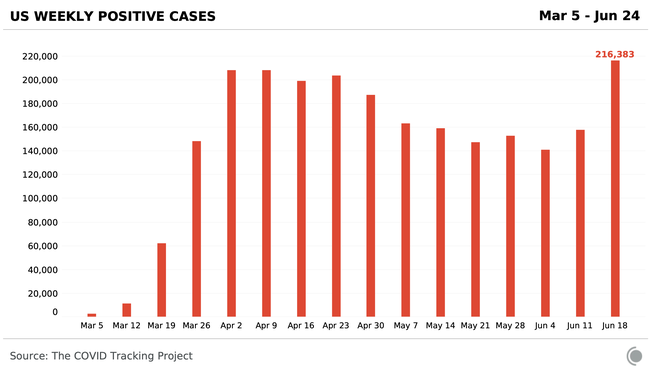

This new surge is large enough to shift the entire country’s top-line statistics. In terms of new confirmed cases, three of the 10 worst days of the U.S. pandemic so far have come since Friday, according to data collected by the COVID Tracking Project at The Atlantic. The seven-day average of new cases has now risen to levels last seen 11 weeks ago, during the worst of the outbreak in New York. The U.S. has seen more cases in the past week than in any week since the pandemic began.

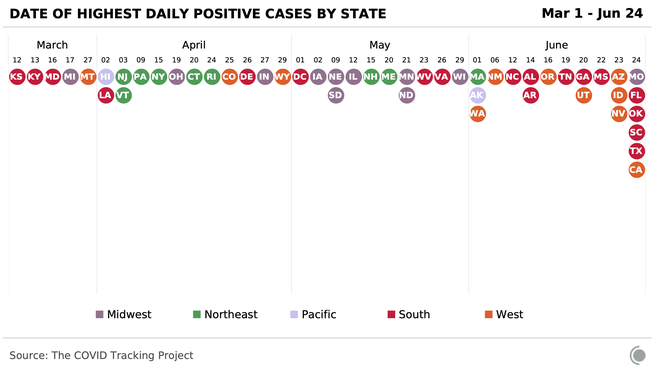

Since June 15, most of these new cases have come in the South. The ongoing outbreak there is the second-worst regional outbreak that the U.S. has seen so far. Only the springtime calamity that befell the Northeast—which was one of the worst coronavirus outbreaks anywhere in the world, if not the worst—exceeds what is now happening across the Sun Belt.

Ominously, sparks from the Sun Belt outbreak may be landing in other parts of the country and igniting new blazes of infection. Since June 15, Ohio and Missouri have seen their average daily case counts increase by the hundreds. Virginia, which battled the virus in May but has so far escaped this month’s surge, has also seen cases rise in the past few days.

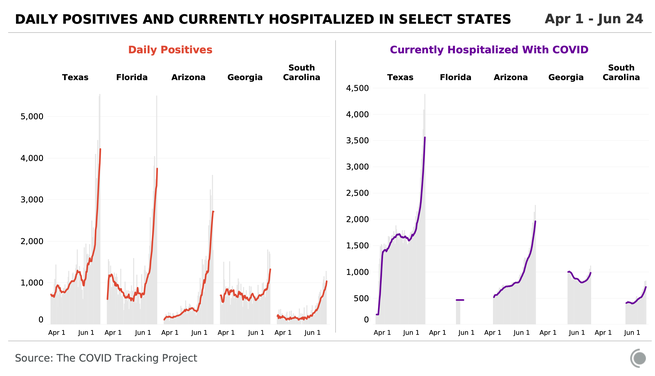

The national surge is driven primarily by potentially disastrous situations in Arizona, South Carolina, Texas, Florida, and Georgia. Many virus statistics in these states now look like straight lines pointing upward. In Arizona, where President Donald Trump held a large indoor rally this week, the situation is particularly bleak. Over the past month, the number of confirmed cases there has grown nearly fourfold; the number of people hospitalized has more than doubled. On Tuesday, the state reported more than 3,500 new cases in one day. That’s equal to 494 new cases for every 1 million residents, a figure that rivals New York State’s numbers in March and April.

Were it not for Arizona’s terrifying surge, spikes in other states would register as major events. Texas has seen an explosion: On June 1, it reported about 600 new cases of COVID-19; yesterday, it reported more than 5,000. Its hospitalizations have more than doubled in the same period. Florida, for its part, has reported an average of 3,756 new COVID-19 cases each day for the past week, a fourfold surge in daily cases compared with a month ago. And in South Carolina, new cases have grown sevenfold since mid-May. The Palmetto State now records nearly 950 new COVID-19 cases every day, or about 184 new daily cases for every 1 million residents.

Across the country, 10 states have set new records for case counts in the past three days.

Why are these spikes happening? The answer is not completely clear, but what unites some of the most troublesome states is the all-or-nothing approach they took to pandemic suppression. The stay-at-home order in Texas, for instance, lifted on April 30. A day later, the state allowed nearly all of its businesses and public spaces—stores, malls, churches, restaurants, and movie theaters—to open with limited capacity. It has since further loosened those restrictions. Arizona allowed some stores and businesses to reopen in early May; it lifted its stay-at-home order on May 15 and allowed bars, gyms, churches, malls, and movie theaters to reopen around the same time. And while the state mandated some form of capacity restrictions, those rules were regularly breached: For weeks, photos and videos have shown scenes of crowded Arizona bars and nightclubs.

A form of wishful thinking seemed to drive these decisions: If the virus could be ignored, then it might go away altogether. Even though polls show that most Republicans wear masks, the Republican leaders of Texas and Arizona catered to the party’s anti-mask fringe and waffled on their importance. When the government of Harris County, Texas—which includes Houston, the country’s fourth-largest city—mandated that residents wear masks in public or risk a $1,000 fine, the state government blocked the rule. Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick called a face-mask mandate “the ultimate government overreach,” and Representative Dan Crenshaw said it could lead to “unjust tyranny.”

Eventually, Governor Greg Abbott of Texas and Governor Doug Ducey of Arizona went even further, blocking cities and counties from implementing any pandemic-related restriction more stringent than that required by the state.* This meant that when a video emerged of packed nightclubs in Phoenix, full of people who were not wearing masks, the mayor was unable to close or sanction the clubs—or even require them to force patrons to wear masks. Both governors finally reversed those policies last week. (“To state the obvious, COVID-19 is now spreading at an unacceptable rate in Texas, and it must be corralled,” Abbot said at a press conference on Monday. This had not been obvious to the governor less than a week earlier, when he told Texans that the state’s record-breaking number of new infections was “no reason today to be alarmed.”)

Yet these decisions do not fully explain the surge. Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida, also a Republican, allowed some cities and counties to wait to reopen on May 18, weeks after the rest of the state; though he criticized face-mask rules, he has not blocked cities from imposing their own. Governor Gavin Newsom of California, a Democrat, imposed the country’s first stay-at-home order, on March 19, and didn’t begin lifting restrictions until May 8. But counties have had wide leeway to enforce their own rules, and Newsom kept some high-risk businesses, such as gyms and movie theaters, closed until June 12. Yet in both states, infections are increasing.

No matter their cause, these outbreaks are now too significant to explain away with statistics. In the past few weeks, President Donald Trump and other officials have claimed that the rise in cases is illusory and due solely to an increase in testing. “Cases are going up in the U.S. because we are testing far more than any other country, and ever expanding,” Trump said on Twitter earlier this week. “With smaller testing we would show fewer cases!”

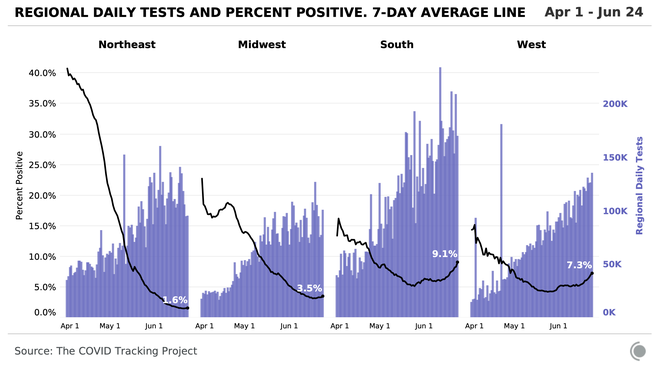

This effect—if you test more people, you have more cases—is obvious enough, but it fails to explain the surge that we’re seeing now. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, disputed the idea that testing alone is responsible for the spiking case count.

“Clearly, if you do more tests, you will pick up more cases that you would not have picked up if you don’t do the tests,” he told The Atlantic. “But—and this is a big but—what you look at is what percentage of the tests are positive. If the percentage of any given amount of tests in one week—take an arbitrary number, [if] 3 percent [are positive]—and the following week it’s 4 percent, and the week after that, it’s 5 percent: That can’t be explained by doing more tests. That can only be explained by more infections.

“When you see hospitalizations, that’s a clear indication that you’re getting more infections,” he said.

The South and West meet all of Fauci’s criteria: Cases, hospitalizations, and the test-positivity rate are spiking in both regions. A month ago, health-care workers in Arizona had to test about 11 people to find a new COVID-19 case; today, one in five people they test has the virus. In Florida, the number of tests per day has actually fallen in the past week while the number of new cases has spiked. The Sun Belt surge, in other words, is not a by-product of increased testing. In the South and West, finding people sick with COVID-19 is simply getting easier.

Felicia Goodrum, a professor of immunobiology at the University of Arizona and the president-elect of the American Society for Virology, has found it painful to watch her state accept its rapidly surging infections with defeat. State leaders “look at the numbers, at the rise in cases, which are staggering, and they say, ‘There’s nothing we can do about this.’ And that’s just not true,” she told us. Face masks and social distancing could still slow the virus’s spread, she said last week, but the state was running out of time.

“We’re reaching this critical point where the only way we’re going to reverse what’s happening is to do a complete shutdown again,” she said. “We’re playing with fire, and we will get burned.”

So much for the fears of a resurgence in the fall. As the first official days of summer unfurl, American coronavirus infections are threatening to bubble over. The virus has not gone away with warm weather, as President Trump once mused that it might. It has gotten worse.

Yet last week, as cases ticked up in the Southwest, Vice President Pence declared in The Wall Street Journal that “there isn’t a coronavirus ‘second wave.’” He pointed out that “more than half of states are actually seeing cases decline or remain stable.” This was the same op-ed in which he boasted that new cases have “stabilized” in the U.S., falling to 20,000 a day.

These numbers are not comforting. The vice president was still implicitly saying that nearly half of states are seeing an increase in new cases. He was also framing 20,000 new cases a day as an accomplishment, even though countries in Europe and East Asia have seen much lower daily case counts on a per capita basis.

What Pence’s op-ed suggests but does not say is that the U.S. never brought its pandemic under control—the “first wave” never ended. And his timing turned out to be dreadful. That key number—20,000 new cases a day—quickly became outdated: The U.S. is now seeing an average of about 30,000 new cases a day. Because more people live in the South than the Northeast, the country could soon record more than 40,000 cases a day, if not more.

A “second wave” was never a good yardstick, because the “first wave” that struck the greater New York area this spring was a disaster beyond reckoning. Consider that New York City, population 8.4 million, saw more than 22,300 confirmed and probable deaths from COVID-19; one of Europe’s worst outbreaks, in the Lombardy region of Italy, population 10 million, saw about 16,500. In three and a half months, in other words, a new virus killed one in every 400 New Yorkers. Among the elderly, the toll was even worse: One in every eight New Jersey nursing-home residents died this spring.

The virus remains the virus. It can take up to 14 days for someone to show symptoms; it can take another two weeks for that person to appear in the data as a confirmed case. This means that, as the Northeast learned in the spring, virus statistics tell you what was happening in a community two to three weeks ago. The South, in other words, may have tens of thousands of COVID-19 infections that it cannot yet see. In the months to come, 20,000 new cases a day will look like a low point of new daily cases—a reprieve in the long horror of the American pandemic.

The outlook is not entirely dismal. Last week, the U.S. met a long-sought milestone: It can now test half a million people each day for the virus. This is more than four times the number of people that could be tested in early April. This means that it may be possible to contain some outbreaks in the South. In addition, the U.S. death toll has been in a slow decline for weeks: About 600 Americans are dying of the coronavirus every day, the lowest daily total since March. This data point may mean that American hospitals are getting better at treating people sick with COVID-19—or it may simply mean that the Sun Belt surge has not yet shown its full lethal potential. For now, the data are impossible to interpret. Because COVID-19 itself can take weeks to kill its victims—and even then the data do not reflect them immediately—we should not expect to see victims of the Sun Belt surge appear in death data for as many as 28 days after it began.

We still have time to save lives. After the outbreak in the Northeast, experts and officials identified several countermeasures that did not require sheltering in place. One of the most important was protecting long-term-care facilities. Because the virus is deadliest for older people, killing about one in every 20 infected adults ages 65 and up, keeping the virus out of nursing homes could considerably reduce the death toll from the surge.

Yet in Arizona, for instance, we have little idea what is happening inside such facilities. Preliminary data from the COVID Tracking Project show that the number of long-term-care facilities and assisted-living facilities with outbreaks has grown from 192 to 268. The virus is still clearly getting in. The state governments in Arizona, Florida, and Texas must do everything they can to stop it—in part by regularly testing residents in these facilities and by building a centralized quarantine site for older adults who have COVID-19 but do not require hospitalization.

A month ago, our colleague Ed Yong wrote that the United States was facing a “patchwork pandemic,” an awful months-long period when the virus would afflict states, cities, and neighborhoods differently. The U.S. now must prove that it can contain one of these flare-ups. New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut—the site of the first major U.S. COVID-19 outbreak—yesterday imposed restrictions on travelers arriving from Texas, Arizona, and other states in the South and West with dangerously high caseloads. The three states will require people arriving from these places to quarantine for two weeks, but their ability to enforce that policy is questionable. The spring surge trained us to think that regional outbreaks could stay contained to a region. But the northeastern surge happened when the whole country was sheltering in place. This moment is different: Can the rest of the country continue to reopen their economies while the South boils over with cases?

On Tuesday, Governor Abbott said that Texans have no reason to leave their homes—essentially asking them to voluntarily quarantine. He has since canceled elective surgeries in some of the state’s hospitals, but said that reimposing a formal shelter-in-place order in Texas is a measure of last resort. Such measures may seem unimaginable now. But if a coronavirus outbreak rips through the state, infecting a large portion of its 29 million residents, then more than just Texas’s health and economy will be on the line.

The spring surge resulted from a widespread failure of American governance. Yet a first coronavirus outbreak in the U.S. may have been unavoidable, and Americans eased its agony by choosing to act together: Our collective decision to stay at home averted an estimated 4.8 million additional COVID-19 cases.

A second surge will allow for no such succor. It will reveal that our leaders, instead of wrestling the virus into submission, gave up on it halfway. That choice will have an unaccountable cost. If several large states plunge into full-scale coronavirus outbreaks, then Americans may need to again act as one—or we will see so much misery that we will yearn for the spring.

*This article previously misstated the Arizona governor's first name. He is Doug Ducey, not Dan.