The Second Battle of Charlottesville

Trump is reliving a defining moment in his presidency—and enacting the lessons he took from it.

The image of President Donald Trump holding aloft a Bible in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church is destined to be a defining one of his presidency. The events that led up to that moment reveal the essential elements of his rise to power. His walk through Lafayette Square was an act of instinct, not an artifact of planning, placing image and symbolism over substance with little thought given to the repercussions. The stunt was roundly criticized, but in Trumpian terms, it was a smashing success—putting him at the center of the biggest story, his image splashed across television screens and the front pages of newspapers all over the world.

Several of the president’s top advisers later expressed shock and dismay, some even voicing their concerns publicly. In the days that followed, a series of retired military leaders offered highly unusual condemnations of a sitting president. But no apology came from Trump, no hint of regret.

Nobody who has spent time around Trump had reason to be surprised. The groundwork for the disastrous photo op was laid long before protesters were forcibly removed from the street above Lafayette Square. The events of recent weeks echo a previous low point of Trump’s presidency: his response to the violence and hate perpetrated by white-supremacist groups protesting the removal of a Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia. The lessons he took from that episode were markedly different from the views of the public at large, and they are shaping his conduct now.

The August 2017 “Unite the Right” event began with a nighttime tiki-torch march of white supremacists chanting “Jews will not replace us.” The images shocked the nation then, just as the video of George Floyd’s killing does now. More protesters arrived for the rally the following day, some carrying flags with swastikas and other Nazi symbols. One drove a car into a crowd of counterprotesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer.

Hours after Heyer’s death, the president read a brief statement condemning “this egregious display of hatred, bigotry, and violence,” and, looking up from the paper he had been reading, he ad-libbed, “on many sides, on many sides.” But for two agonizing days, he failed to specifically denounce the racists behind the attack in Charlottesville. You wouldn’t think the president would need to be persuaded to make a statement condemning neo-Nazis, but as public pressure mounted, Trump’s advisers pleaded with him to condemn the hate groups and offer words of empathy and reconciliation.

Trump finally agreed to give a short teleprompter speech declaring “Racism is evil” and calling out hate groups by name. Before the president stepped before the cameras to read the statement, his newly installed chief of staff, John Kelly, summoned FBI Director Christopher Wray, then–Attorney General Jeff Sessions, and then–Homeland Security Adviser Tom Bossert to the White House to meet with the president. The official reason given for the meeting was to update the president on the federal investigation into Heyer’s murder. Kelly also had an unofficial reason for calling the meeting: He wanted to make sure Trump would go forward with his scripted remarks.

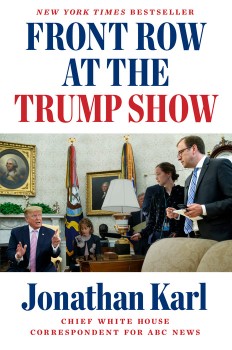

The president met with these top law-enforcement officials on the second floor of the White House residence, in a grand space overlooking the South Lawn known as the Treaty Room. In my book, Front Row at the Trump Show, I reported the details of this meeting for the first time, based on conversations with three of the people present, all of whom spoke on the condition that I not use their names. One of the participants shared with me contemporaneous notes on what happened.

The president sat at the Treaty Table, an enormous desk that President Ulysses S. Grant used for Cabinet meetings and where the treaty ending the Spanish-American War was signed in 1898. Sessions and Wray sat directly across from the president; Bossert and Kelly sat around a coffee table off to the side. Two other aides stood by the door to the room.

As the meeting began, Sessions told the president what the federal investigation of Heyer’s murder would entail. There was some discussion about whether it could be declared an act of domestic terrorism. But the president quickly took over the meeting. He wasn’t interested in getting a briefing on the investigation. He had other things on his mind.

The protesters, the president said, were being treated unfairly. The majority of them, he insisted, were there for a good reason—they did not want to see the statue of Lee removed.

Turning to Sessions, the president asked whether he thought the statue should come down. Sessions said the decision should be up to the local community, in this case, the Charlottesville city council, which had voted to remove it.

But the president was just getting started.

According to the notes from the meeting, the president, sitting there at the table Grant used, declared Lee “the greatest strategic military mind perhaps ever.” He also praised the Confederate general Stonewall Jackson. He made clear that the Ku Klux Klan and the neo-Nazis were “bad,” but also seemed to dismiss it as too obvious a point. Instead, he was focused on the protesters’ right to be there, and the unfairness of the way they were being treated. To Trump, the protesters were taking up a good cause by fighting to keep the statue of Lee in a prominent place.

“Next will be Washington and Jefferson,” he said, then, looking around to everyone in the room, he asked, “Does anyone think this is fair?”

Nobody jumped in, either to agree with the president or to challenge him. Nobody in the room suggested to him that praising Confederate generals was inappropriate for a president to do under any circumstances, especially after all that had just taken place. In fact, Kelly chimed in to agree with him on the greatness of the Confederate generals and on his point about Washington and Jefferson.

The others sought to keep Trump focused on the need to make a clear statement condemning the violence and those who had started it. Wray tried several times to bring the conversation back to the subject of the briefing, telling the president it was imperative that he specifically name the Klan and the neo-Nazis as the groups behind the violence.

But nobody in the room was willing to confront the president and tell him the issue was not that the protesters were being mistreated. The protests had been led by virulently racist groups that had provoked the violence that killed Heyer; that’s what shocked the nation. Kelly was new to the job, as was Wray, who had just been named the FBI director two weeks earlier. Bossert had been in his role longer, but he wasn’t particularly close to Trump. And Sessions’s standing with the president had been precarious for months, since his decision to recuse himself from the Russia investigation.

As the meeting ended, the president looked to the two staffers standing by the door.

“Do you want to see the Lincoln Bedroom?” he asked.

And with that, the group walked out of the room, to the right, and into the Lincoln Bedroom. Just moments after praising two Confederate generals, the president was gushing about Abraham Lincoln. Pointing to the unusually large bed and the full-length mirror, he talked about how tall Lincoln was. He showed off the handwritten version of the Gettysburg Address, which he said was regarded as “the greatest speech ever,” and, with glee, told the group how newspapers at the time panned it as a terrible speech. The implication was clear: The “fake news” hated Lincoln then just like they hate Trump now. As he would later say in an interview with George Stephanopoulos: “Abraham Lincoln was treated supposedly very badly. But nobody’s been treated badly like me.”

From the Lincoln Bedroom, the president went downstairs to deliver his speech. He had vented in private about how unfairly the Unite the Right protesters in Charlottesville had been treated, but when he stepped in front of the cameras in the Diplomatic Reception Room on the ground floor of the White House residence, he did exactly what Kelly and others said he must: He read the statement, specifically and unequivocally condemning the white supremacists.

“Racism is evil,” he said. “And those who cause violence in its name are criminals and thugs, including the KKK, neo-Nazis, white supremacists, and other hate groups that are repugnant to everything we hold dear as Americans.”

The president’s remarks were carried live on all the cable-news channels and as a special report on the broadcast networks as well.

When he was done speaking, Trump walked into the hallway with several of his aides, including Kelly and then–Press Secretary Sarah Sanders. They ducked into the nearest room with a television—a small room on the ground floor used as the office of the White House physician, then Ronny Jackson—to watch how the speech was being received.

Jackson’s office had more than one TV, which made it possible for the president to see how his speech was playing on Trump-friendly Fox News as well as on CNN and MSNBC.

He was outraged by what he saw. Commentators on CNN and MSNBC were calling his comments too little, too late. On Fox News, the statement was called “a course correction.”

The president listened for a few minutes, then turned to his aides.

“This is fucking your fault,” he said. “That’s the last time I do that.”

For the next few hours, Trump stewed about how his remarks were received. He said over and over again that it had been a mistake to make the second statement, because, in doing so, he was effectively acknowledging something was wrong with the first one. He was convinced it made him look bad. It emboldened his enemies.

The next day, the president went before a group of reporters at Trump Tower. This time, his remarks were unscripted—and unforgettable. Instead of repeating the condemnations of racism he’d offered the day before, he repeated in public much of what he’d said to his aides in private. There were, he told the country, “very fine people, on both sides” of the protests in Charlottesville, “very fine people” marching together with white supremacists.

Never again would he be browbeaten into delivering a speech of reconciliation, a speech unequivocally condemning racial injustice and violence. Never again would he let anybody talk him into admitting a mistake or doing anything with even the faintest hint of an apology. There would be no more course corrections.

This post is adapted from Karl’s recent book, Front Row at the Trump Show.